Atlantic Wall bunkers possible Re-use. Strategies for the re-appropriation of a forgotten heritage.

#concealed STUDIO

Abstract

The Design Studio has developed a project aimed at enhancing the remains of the Atlantic Wall, fostering the recovery of several artefacts completely forgotten and hidden from the everyday gaze, in order to promote Le Grand Tour de l'Atlantique: an equipped path, similar to the great alpine tracks, where simple bivouacs allow the division of the crossing into stages, acting as "points of support" (Stützpunkt). This is a journey in the places of the Great War, in memory of those events, along an extraordinary coastline rich with countless elements of cultural and natural value, but also in contact with monumental ruins full of history. The project explores ways of re-appropriating both these hidden interiors and their monumental landscapes.

The Atlantic Wall (AW) is a fortified Atlantic coastal infrastructure erected by the Nazis during World War Two, in order to protect the Atlantic coastline stretching from the Pyrenees to North Cape from the much-feared Allied landings. This immense defensive line was supposed to be composed of 15,000 buildings (of which only around 12,000 were actually built) set out strategically along nearly 6,000 km, with an average inland penetration of several kilometres. Despite these stunning figures, as well as the remarkable amount of buildings still standing and the dramatic related memories, the AW has been largely disregarded or at least underestimated as to its potential to narrate the events that brought it into being. This is proven by the overall state of abandonment in which most of its structures stand: the progressive decay of an uncomfortable heritage. A system of spaces and objects removed from the everyday gaze due to their dramatic past.

The AW educational experience was viewed as an important piece of a larger puzzle aimed at the re-appropriation of special hidden interiors completely removed from collective memory for their highly problematic heritage: finding a way to voice their material and immaterial value. In fact, the theme was chosen with the aim to give a new semantic dimension to objects – bunkers and other military buildings – generally forgotten or deliberately excluded from everyday life, setting them within a broad unifying framework. Therefore, the objective of the course was to explore possible processes for the re-appropriation of the AW’s artefacts, considering the infrastructure as the largest European transnational shared memory, a possible tool for enhancing inclusive dynamics instead of conflictual ones[1] typically connoting these interiors [Figure1].

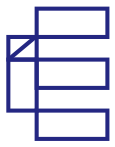

This interpretation and mapping were possible owing to the discovery, analysis and assembly of iconographic and cartographic documents which allowed for the reconstruction of an archaeological landscape of the conflict, recognising its great expressive and testimonial potential as well as its aesthetic-landscape value [Figure 1]. A practical step supporting the themed itinerary - which we called Le Grand Tour de l’Atlantique – was the creation of a large map of the AW, capable of restoring the meaning and overall readability of its heritage made of places and buildings, history and memories: putting AW rooms one after another. While mapping the territory, as a natural integration, students catalogued their interiors according to the functional typology, trying to grasp, at the same time, the potentially figurative value of their interiors[2]. The consideration of the formal and material qualities of the buildings – that somehow transcend the unavoidable testimonial value, bringing them back to the condition of architecture – triggered the planning phase aimed at their reassessment.

Students were asked to draw up assumptions on how to enhance this cultural landscape, making the relationship between man, environment and memory somehow more accessible and understandable, through different interpretations aimed at bringing back to life their spaces: from defensive rooms totally inaccessible to welcoming interiors opening up their space to the “foreigner”, to the “other”, the “unexpected” one. Indeed, the places where the AW bunkers are located have a spectacular quality. Therefore, we asked the students to investigate this aspect by highlighting the relationship between their interior spaces and the landscape. The bunkers, set in this evocative context, were reconsidered as belonging to an integral narrative process where the direct experience of the artefacts is once again part of an extended and complex territorial system. Taking into consideration the bunkers objective - to watch over a specific section of the territory, they were re-designed as optical cameras capturing the surrounding landscape. The common starting point was based on the fundamental idea of building new bridges between people, artefacts, places and history, turning these difficult and hidden interiors into a tool for the re-appropriation of the territory and the landscape. Using this strategy, the students’ proposals began by disrupting the unheimlich quality of the AW and its wartime identity in favour of new possible horizons. To this end, Giorgio Agamben’s poetic power was used recalling the following phrase: ‘If to consecrate (sacralise) is the verb that describes things leaving the sphere of human law, by contrast to profane means to restore them to man’s free use. […] Deactivating an old use making it inoperative, potentially generates a new use’[3].

The proposals were thus aimed at restoring the AW hidden interiors and their natural context to the direct experience of nudo luogo (bare place): through minimum linking interventions and devices capable of connecting them and assigning them a poetic use, the AW rooms were reconsidered as milestones of a themed itinerary. The system of paths and small equipped spaces re-connecting the bunkers – in turn reconsidered as places where it is possible to stop and build relationships – was designed as a means to re-approach and enter into contact with WWII history in a reconciliatory view: on the one hand, the path reveals the testamentary scope of the dramatic events that left their mark on it, and on the other, it attempts to offer itself as a meeting point for people geographically and culturally distant, where they can enter into new relationships, radically transforming what was hidden into a manifesto[4]. The sense of Le Grand Tour de l’Atlantique is based on the attempt to reconsider this painful heritage as a possible reconciliation between places, events and people through the observation, reflection and use of a territory studded with material and immaterial traces. Through the different design proposals, these forgotten interiors are literally restored to the public gaze, in a physical and symbolic process able of translating simple practices into vectors of new dwelling models.

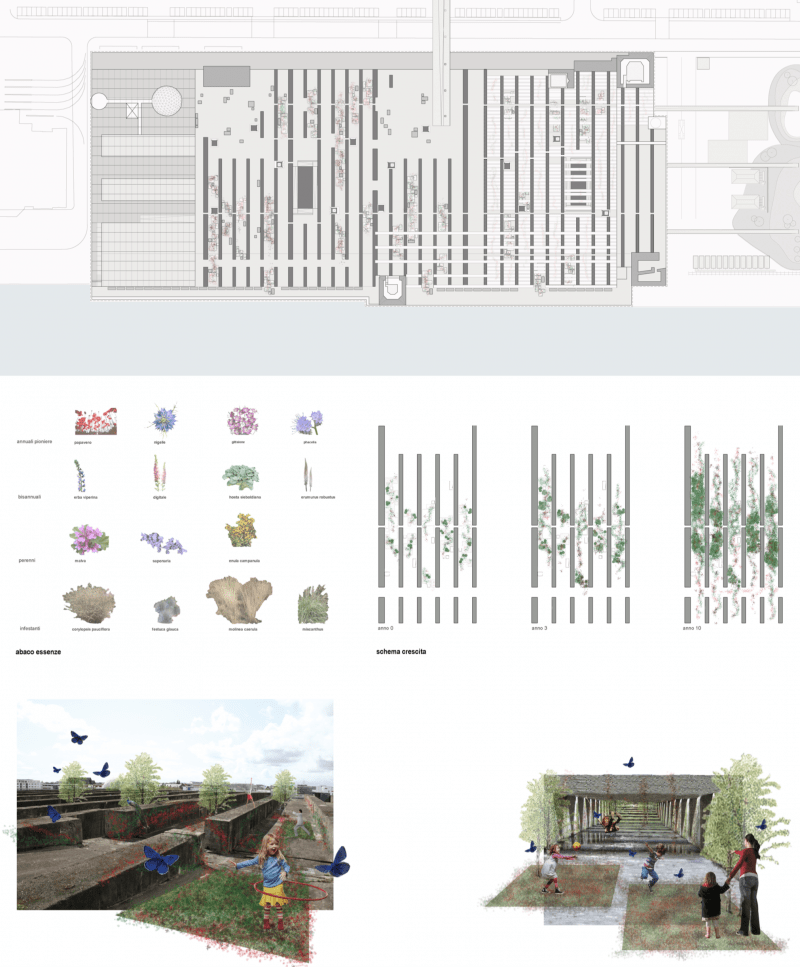

On such a basis, the proposal formulated by students Daniela Canzi and Ester Golia was based on the attempt to rediscover the AW as an architectural artefact which, beyond its bond with the past, can be recognised by visitors while they regain its possession. The project methodology progresses in parallel with the strategy and approach used by the Germans for the construction of the AW: standard and repeatable buildings positioned in a vast and diversified territory according to precise requirements provided in the Regelbau. Starting from the AW state of abandonment, the aim of the project is to bring to light the entire defensive system observing it from points of view that are different from military logics, especially through unexplored viewpoints such as the architectural, landscape and aesthetic ones. Therefore, it is organised on the basis of a three-level standardised hierarchical information system drawing inspiration from the settlement criteria used by the Germans, with the aim to restore the AW to its original identity of unitary artefact drawing strength and meaning from the fact of being a system of correlated junctions and where the mono-functional hidden rooms play a key role. The first level of the new design is the national one. Each country is provided with a national historical archive relating to the AW. The second level of information involves a system of info-centres all alike in different points of the coastline. The information centres follow a particular settlement criterion that draws inspiration from an analysis of the quantity of concrete used in the construction of the AW. The third and last level is mainly local and is connected to each single interior grafted along the defence line with the task to provide information in the specific place. Using the AW rooms typology as a design strategy constitutes the most practical modality for providing information on its hidden nature against its natural manifested context.

Other interesting proposals were those in which the bunkers forgotten interiors were simply restored to their original function as landscape point-of-view, without a full-blown transformation in their use. Gigantic cameras focusing on the horizon, eternally awaiting the event for which they were built, as in The Longest Day (1962, movie directed by Ken Annakin, Andrew Marton, Bernhard Wicki, Darryl F. Zanuck).

At the end of the educational experience, the laboratory results were exhibited in the patio of Politecnico di Milano. Along with the students, we created an exhibition system based on the reproduction of one bunker interior on a scale 1:1 and a series of images put together in a “panoptic order” capable of generating a strongly experiential path that recalled the planimetric situation of the Stützpunkt of Soulac-Sur-Mer, along the French Atlantic southern coastline. To access the hidden interior, naked of its wall depth reduced to a simple skin, manifested strongly the wish to neutralise its scary but powerful presence. The choice to reproduce one room interior trying to respect not only its dimensions but also its enormous mono-material structure, required great effort rewarded by the immersive visual experience. Even the circular order of the 360° panorama – positioned on the basis of the bunkers position in the landscape – was conceived with the intention to reproduce a privileged spatial dimension and experience in order to observe the landscape of/from the bunkers with new eyes - the same horizontal view characterising human perspective and thus re-appropriating the hidden interiors of the AW exactly with the same gaze that was before excluded [Figure 3].