Open Neighbourhoods. Disclosing the hidden potentialities of urban interiors

#forgotten STUDIO

Abstract

This paper seeks to report the ten years of didactic experience developed through the Interior and Exhibition Design Studios, which were part of the Interior and Spatial Design Masters degree course at Politecnico di Milano. Open Neighbourhoods. For a genetic evolution of the urban metabolism is the common title assigned to the labs, whose aim has been to read, interpret and rethink the contemporary value of the “Interior Design” discipline, exploring the vast “open” field of design research related to the most erratic and hidden ways of inhabiting spaces.

1. Open Neighbourhoods. For a genetic evolution of the urban metabolism: a common design approach and method

During recent times, the metropolis has been hit by radical transformations of the global era. Deindustrialization has brought about the problem of disused areas and buildings, small commercial activities have been overtaken by multinational chain stores, social housing has been undermined by the big real estate of the Nineties. This socio-economic situation urges design disciplines into action, to address the agency of design in establishing a new relationship with reality. Hidden interiors can be found where the globalization disrupts local communities, made of small commercial activities, social relations, familiar and symbolic landmarks of every city zone.

Open Neighbourhood. For a genetic evolution of the urban metabolism has been the common title of the didactic experience developed during the Interior and Exhibition Design Studios led by Giampiero Bosoni, Ico Migliore and Chiara Lecce as part of the Interior and Spatial Design Masters degree course at Politecnico di Milano: a ten year long (2009-2019) didactic experience declined through different spaces, projects and modalities with more than 400 students involved and 50 final theses elaborated; a title which indicates a design approach oriented to a reinterpretation of the “Interior Design” discipline, exploring new and hidden ways of inhabiting spaces in the urban environment. The Open Neighbourhoods’ design approach has been generally set into three steps:1. Occupy Urban Voids; 2. Enhance Existing Realities; 3. Temporary Interventions.

Defining a genetic evolution of the urban metabolism inside the diffused city[1] starts from the word metabolism (from Greek: μεταβολή metabolē, “change”) which is the set of life-sustaining chemical transformations within the cells of living organisms. These enzyme-catalyzed reactions allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Similarly, the students were asked to analyze, explore, interact and finally respond to the urban realities exposed to them during this period. Most of the time the research focused on different typologies of hidden interiors, more precisely urban interiors.

The contemporary metropolis, in this specific case the city of Milan, has been dissected and investigated through its hidden places: infrastructural in-between spaces and urban voids, underground spaces, forgotten and abandoned interiors, all “invisible landscapes”[2] equally sharing interior and exterior urban realities. As stated by Arianna Veloce for the article Urban hybridization. Regeneration techniques of the city’s consolidated tissue: ‘The external space will be merged into the internal one for a final hybridization in between public and private, in between city and buildings. Imaging an urban structure in which events, scenarios and different landscapes are strictly hybridized between themselves, the possibility of a perpetual mutation emerges by the idea of a restored urban genetic code capable of triggering chain transformation starting from a mutation of one of its single entities’ [3].

So, the concept of genetic evolution of the urban metabolism meant a design vision that bases itself on the analysis and an innovative critical observation of the contemporary (and next venture), conditions of living in the flow of transformation of urban areas. The design method adopted during this time has been generally articulated in: a first phase of meta-design research (problem setting) dedicated to analysing the urban reality and pick up significant case studies, in order to individuate innovative scenarios for the city’s usability and for the new generation of “living behaviors”; and a second phase of design concept (problem solving) and project definition in terms of communication and technical arrangements.

Starting from the first phase, students had to immerse themselves into the neighbourhood where their project was located: in order to capture inhabitants’ feelings and memories of the place, individuate commonly recognized local landmarks, commercial activities, cultural spaces, contacting zone associations, know the history and the geography of the site and, above all, try to understand the reasons why that place has been marginalized or abandoned, hence hidden within the cityscape.

In the end, students had to understand, as much they could, the series of socio-cultural, political and urbanistic dynamics interacting with the place and consequently seek for its hidden potentialities. The hidden potentialities were then translated into a design concept which didn’t mean, for instance, a simple redesign or an embellishment. The concept had to transform critical analysis into revitalizing design projects. Starting with a programme of activities, the concept had to imply strategies that could interact with and react to the context, define a set of functions and sustainable services, comprehend (from the very first steps) a communication and brand identity strategy in order to make the project visible.

In parallel with the analysis of the area of the project, students received a specific theme of research, correlated with the lab’s main topics, in order to create a collection of rich case studies that were shared and used collectively by all the other students. Open Neighbourhoods has always individuated a specific design approach where the potentialities of temporary design interventions were conceived to redefine empty spaces into dynamic settings: projects for temporary construction which, unlike conventional architecture have no clear-cut divisions between the inside and outside. It might be referred to as “architecture with time limit”, which is not conceived to be permanent, even though it sometimes actually becomes so, and whose ultimate aim is to provoke thought and arouse feelings. In constructing these artificial landscapes, a project develops and evolves around themes and issues to be communicated and is implemented by means of a smoothly flowing process for supplementing and stratifying the various elements required for its construction, such as light, graphics, images and structures.[4] The long term action of the Open Neighbourhoods labs has demonstrated also another relevant characteristic of this kind of temporary intervention: small ephemeral projects based on a sensitive understanding of the local (hidden) potentialities: bringing a qualitative design concept can actually trigger the durable reconfiguration of entire urban areas – a phenomenon that has regularly occurred over the last ten years with several examples around the world.[5]

The temporary nature of the Open Neighbourhood has promoted projects in urban areas in need of regeneration: spaces that were something in the past, that lie abandoned in the present and their future reconfiguration is variably estimated to happen in ten or twenty years - temporary design programmes proposing new functions that arguably will have a long-term effect.

Indeed, we can define them as hidden spaces (or hidden urban interiors from our perspective). In order to have a close-up of the Open Neighbourhood outcomes, a selection of four design studios from the last ten years is discussed here, rereading them through typologies of hidden urban interiors such as: “hidden neighbourhoods”, “hidden underground”, “hidden micro architectures”, “hidden in-between”.

2. Hidden Neighbourhoods

Students had to confront this reality and design a new “open” system of spaces, activities, events and services able to appreciate the many bottom up enterprises active around the area. The proposal was to create a dynamic network of new “galleries”, to ideate original social and shared (both material and cultural) places, service and communication spaces, innovative retail systems, new exhibition forms. The process, keeping in mind the historical memory of the neighbourhood, has identified keys to future interpretation and outlook.

Students discovered a multifaceted quarter with a strong community feeling (despite the multiethnic co-existence), with several hidden resources made of abandoned shops and degraded public areas that would be transformed into vital social and economic activities. A place where marginalized communities had developed a strong attachment to the neighbourhood, re-generating the street’s vitality and micro-economy.

Students elaborated heterogeneous projects working both on interior and exterior spaces: some of them designed along all the 1.5km extent of via Padova, imagining new services like a bicycle path or communication systems linked to the bus stations, such as the case of “Artigianato 56” by Chiara Cannizzaro and Sabrina Danella. The project took advantage of the bus line 56, that covers all the road, in order to rediscover forgotten handicraft places like the shoemaker’s shop, a lute maker’s atelier and a carpentry laboratory, where young migrant apprentices are learning from old Milanese artisans.

Other students concentrated their concepts on revitalizing several abandoned commercial spaces, like the project “milanopen” by Bori Fenyvesi and Noemi Monus which boosted social connections for the residents: ‘In the empty shops we decided to make a temporary system, with cultural functions, like cinema, theatre plays, or live music. Temporary because the concept considers that these functions take place when shops are empty and not yet rented, so all the designed elements are mobile.’

Other similar projects considered community sharing systems of services, secondhand shops, art installations along the street or setting up new collective places from degraded public gardens like the case of “Il Grande Tavolo di Via Padova” by Natalia Rueda, Christine Urban and Violeta Babatzia: ‘Via Padova is not a dangerous street, as it is often considered. The people of via Padova are responsible workers with families, people who seek a better quality of life, who want to be productive and useful to the community. It is a street full of life, with shops, telling a lot of stories. The aim of our project was to find a place where the inhabitants of via Padova could socialize and learn to share common spaces, and in an abandoned public park we found a 34 meters long structure which was a sort of platform roof with low brick walls on the sides’[6]. The idea was to imagine a long table running under this structure, which could act like a meeting point, an integration place where it was possible to play, study, organize birthday parties, eat and read, dividing the table into three parts: a working area, a play area and a barbecue area.

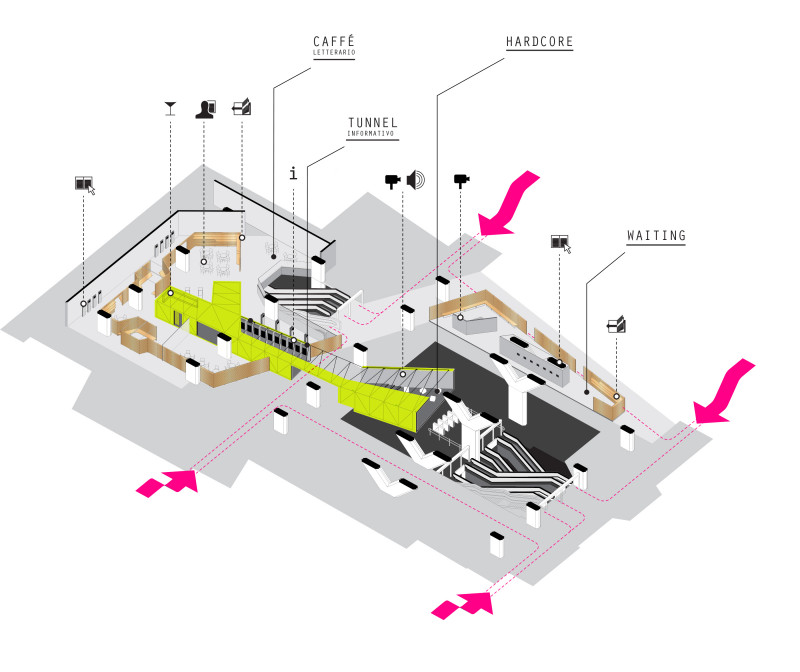

3. Hidden underground

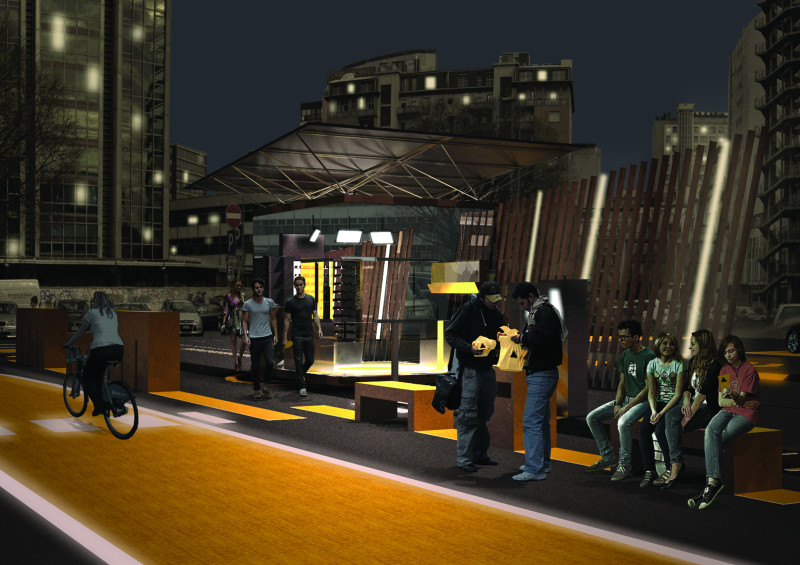

4. Hidden Micro Architectures

“Dehors” Final Synthesis Studio of the Interior Design Masters degree, faced in 2013 the loss of newspaper kiosks within the city of Milan: disappearing commercial activities that are seriously suffering in relation to the printed paper market global crisis. At the same time, these small architectures, spread among the urban tissue, often represent a community reference point in the neighbourhood. In fact, the newspaper kiosk is a typical element of Italian cities and although small scale, it is a pervasive and recognizable object within the urban context - a hidden micro space which is getting lost in the global digital market. The lab challenged the idea of re-functionalizing the kiosk taking advantage of its widespread selling network, integrating its primary commercial nature with renovated meeting and consumption spaces able to activate the local micro economy and social cohesion. The meta-design research phase was dedicated firstly to a detailed exploration of a range of typologies of microarchitecture (social innovation, food, materials and interactive technologies, information, mobility, business, entertainment, urban ecosystem, urban space, citizen services). Then the groups were assigned to specific Milan neighbourhoods in order to map all the existing newspaper kiosks, analysing critical situations and successively choosing one of them as the subject of their re-functionalization project.

“The Newsbook Project” by Sara Maniscalco and Riccardo Mara for example offered a personalized newspaper, seeking the collaboration between different publishers and offering the consumer the possibility of collecting a proper selection of news, printed on demand [Figure 3].

“ZTA” by Maddalena Guglielmelli and Elena Meroni foresees the big contemporary trend (almost four years in advance) of food delivery systems. Starting from the kiosk located at the busy crossroads between via Pirelli and via Melchiorre Gioia, the students designed the “Zona Take-Away”, a small space perfectly organised to prepare food for take away, particularly targeted for workers’ lunch (but easily extendable) [Figure 4].

5. Hidden In-Between

Second Hand / Second Life. Magazzini Raccordati. Proposte per il riuso e la rifunzionalizzazione dei Magazzini Raccordati di Milano has been one of the last Open Neighbourhood labs (A.A. 2017/2018). I Magazzini Raccordati are abandoned warehouses derived from a system of rails that still run along the tunnels excavated under the elevated rails of Milan’s Central Station. The warehouses hosted for many years (from the 1930s to 1980s) several wholesale activities that arrived directly by train. Starting from the 70’s, warehouses were gradually abandoned because of the predominance of different systems of goods distribution (principally traveling on wheels). The result was 140 warehouses of 356 square metres each (12,5 x 28,5 m), for a total of almost 50,000 square meters of empty space extending on two sides (Via Sammartini and Via Ferrante Aporti) for 1.5km.

The common theme of the lab was based on the concept of “exchange” (scambio) attributed to new retail spaces and articulated into ten themes (music, apparel, art, food, children, house, electronics, sport, books and brand identity) to be tested inside the fascinating and hidden tunnels of Magazzini Raccordati. A strategic element in regeneration projects is communication design - sort of brand identity able to expose and explain the design approach. During the work on Magazzini Raccortdati two groups of students were chosen to design the common brand identity for all the other students’ projects: one developed along the street front of the warehouses and the other one inside the long tunnel that connects internally all of the warehouses which still contain the tracks of the original railway.

6. Conclusion

The research work carried out by the Open Neighbourhood labs has been an attempt to interpret some of the complexities of ‘(…) an epoch in which conditions of social, cultural, and economic crisis (…) are the premise for any sort of social, cultural and economic growth.’[10] Andrea Branzi’s theories expressed in his renowned book Weak and Diffuse Modernity: The World of Projects at the Beginning of the 21st Century is used here to strengthen the concept of urban metabolism and its hidden interiors: ‘To modify according to one’s own living, productive, commercial, or promotional needs the space inherited from earlier processes of dismissal produces a sort of urban metabolism. This metabolism is difficult to predict or govern because it is linked to the interrupted currents of this new relational economy. A very similar situation is now occurring in many cities of the industrial world. (…) Many of the new economy’s typical activities have found a home in dismissed areas, entire creative districts set themselves up in abandoned industries, finding this submarket prizes, adequate services, and evolved forms of “incubators”’[11].

Branzi’s reflections dated 2006 bring us back to the present day where we can observe the tangible consequences of these “weak” mutations of urban metabolism. Hidden urban interiors embody precious potentialities because of their deeply-rooted connections with the context (even if its original nature was completely different than the future one), disclosing new (and unexpected) forces inside the neighbourhood. Acting like sort of “hunters” of hidden spaces, students have developed during these ten years a series of design solutions able to disclose these forgotten interiors, making them newly visible.

The interest around hidden urban interiors has grown during these last ten years confirming the thesis that sees temporary design interventions as a possible agent of transformation over a long time period. Exploring hidden urban spaces will continue to be a stimulating field of research and reflection in order to take advantage of the hidden potentialities that are essential enzymes for urban metabolism.