Introduction

Interiors – both public and private – can be invisible to the eye, hidden from view for many reasons, either by chance or as a deliberate act of concealment. There are interiors that are lost - invisible because they no longer exist in a physical form; erased, all traces of inhabitation removed; or forgotten, lacking a way of voicing their material and immaterial value. Others are shielded from public view because they are buried beneath the surface, sealed off, or locked in - too sensitive, important or fragile for inhabitation. Further there are also some typologies of building that negate the essence of the interior – that is, the capacity to allow exchange between people and space.

Issue #4 of IE:Studio explores the range of interpretations that emerge from the investigation of these hidden, invisible and erased spaces. Today digital technologies provide us with pseudo surgical tools through which to record, document, extract and reproduce interiors that are threatened, hidden or concealed, but what tactics and tools can we adopt to take apart, read and interpret the multiple layers of memory and matter that are embedded within the fabric of the interior? What happens when we encounter content and data that poses ethical and political questions? And in the uncovering of such interiors are we aestheticising trauma rather than simply unpicking the truth? Can the increased scrutiny of what lies beneath the surface of the interior give spaces their own agency beyond human inhabitation?

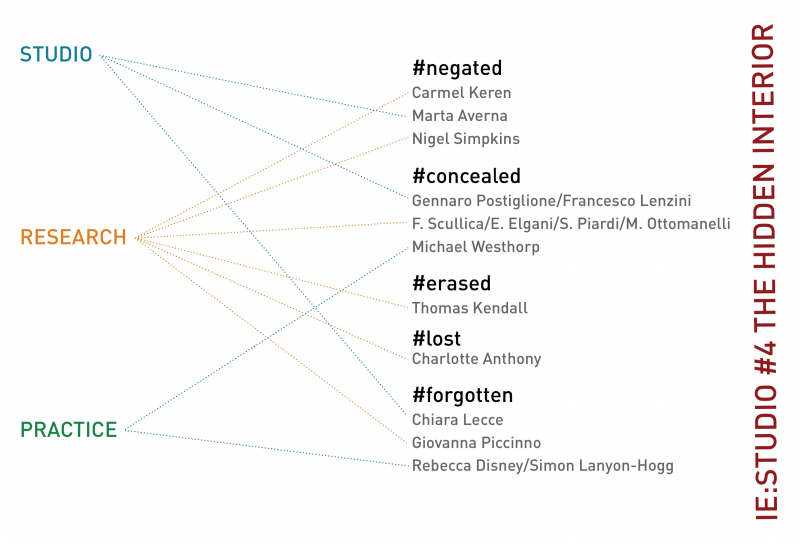

This issue offers a diverse collection of essays and studio briefs that question and expose a range of positions in relation to lost and hidden interiors, and what happens when these spaces are restored to the public gaze, literally and/or metaphorically. The eleven papers included here are organised into three sections: Studio, Research and Practice, and have been curated under five headings: #negated, #forgotten, #concealed, #erased and #lost that identify different typologies of the hidden interior as well as varying strategies of engagement. The three different sections - Studio, Research, Practice – provide a useful framework for how Research and Practice in Interiors informs Studio briefs. The wide range of contributors including academics, researchers, students and practitioners together underline the collaborative nature of interiors as a discipline.

Some of the papers document STUDIO briefs and student responses to them. For example Marta Averna’s analysis of the Colonie in Northern Italy – a legacy of its Fascist heritage – and the student projects that re-conceive their interiors through a strategy of overwriting the traumatic history of these spaces with the identification of new narratives. Gennaro Postiglione and Francesco Lenzini’s essay examines the Atlantic Wall – an example of a fortified coastal structure built to protect the Allies from invasion during the Second World War – questioning the potential for this abandoned set of structures to operate as a device for reconnecting our past, present and future by restoring its hidden spaces to the public gaze. Chiara Lecce’s discussion of the Open Neighbourhood offers a strategic methodology for transforming the meanwhile spaces of Milan, in order to catalyse ongoing and sustained development. Here student work is intimately contextualised and catalogued.

Others papers describe academic RESEARCH that inform teaching such as Silvia Piardi, Francesco Scullica, Michele Ottomanelli and Elena Elgani’s investigation of the smart factory, considering its relationship to context and to inhabitation, and Nigel Simpkins study of the camera obscura as a device that articulates a relationship to the city that is intimate and hidden. Charlotte Anthony offers her research into the Keskidee Centre in London – a building that no longer exists – establishing a methodology for investigating and documenting interiors that have been erased. And Giovanna Piccinno explores the locus of the ‘contemporary nomadic citizen’, contemplating the ‘dematerialization of physical space’ within a network of digital interactions.

Thomas Kendall’s paper, ‘The Juniper Tree’ is experimental, testing the space of the page as the site of erasure and exploring the impact of gaps in the narrative, missing letters, words and paragraphs, as well proposing that text is itself spatial and thus inhabitable. Carmel Keren’s essay is also propositional, speculating on the capacity of Google Street View to freeze time and capture lost narratives of inhabitation.

Michael Westhorp’s paper offers an insight into PRACTICE by designing a hidden typology – the gay sauna. His project grapples with the question of visibility both in terms of the activity that the sauna accommodates and in the materiality of the interventions made. Rebecca Disney and Simon Lanyon-Hogg explore methods of detection that reveal the long-held secrets that the interior holds on to, and test these strategies to construct a new archive for a ‘forgotten and overlooked space.’

The papers here all look to describe buildings and spaces that have disappeared or remain deliberately concealed - a complex interior landscape that is investigated, deciphered and re-presented using an array of methods and tactics. Such investigations are especially relevant to academics and practitioners of the interior as they address the physical and emotional complexity of the environments that frame our lives. Further the disentanglement of the multi-layered realm of the interior offers new visions for its future as an ongoing archive of human experience.