Introduction

The city is the interior. It is where our discipline began. It is our provider and provocation; a shifting, challenging, enriched, antagonistic context for our practice. Its cultural, economic and physical offer is an Interior Designer’s brief, providing a dynamic context through which commissions are offered and ideas are born.

Context for the interior is a complex discourse, underwritten by the principle that the Interior is an inherently synthetic condition and that the successful practice of its design requires the designer to choreograph and curate diverse factors and understanding. At the scale of the city, the urban and architectural setting, the historical and socio-economic circumstance of the interior’s creation and its subsequent development has not always been prominent in either the production or critique of interior design. It was on this basis that the conference theme was proposed.

Contextual thinking has been more prominent, or more overt, in education. Student projects readily engage the physical context of and beyond a site and project briefs have evolved to engage the social and economic conditions informing a programme, integrating these into students’ investigation and consideration.

The papers in this issue reflect Interiors students’ engagement of history, social response, interpretative acts, and the evolving typologies that as designers we articulate and make tangible. They also demonstrate the increasing engagement with other agencies and concerns by introducing students to the matrix of interests, including their own, necessary to design the interior.

This approach is evident in two of the papers included here, albeit in quite different ways, and working with students at different stages in their studies. Orit Sarfatti and Andrea Placidi’s ‘the homeless project’ demonstrates the value of integrating a client, Crisis, who brings an explicit expertise and position into the studio to stimulate another understanding of Oxford city centre and its inhabitation. This informs the design process and challenges pre-conceptions and received values through the direct engagement of the students.

The underpinning of the Interior Design students’ professional knowledge and imagination with the awareness of their social and cultural responsibility is critical. The cultural context, the capacity to anticipate, engage and provoke change; the means to reveal what is not seen, is part of that role.

Change and the responsibility to what remains, what is left behind and, critically, the people who contribute to (or are affected by) the designer’s acts are not simple criteria. In the city these can be immediate, economically or technologically charged but simultaneously rooted in histories and narratives that weave a rich matrix of culture and place.

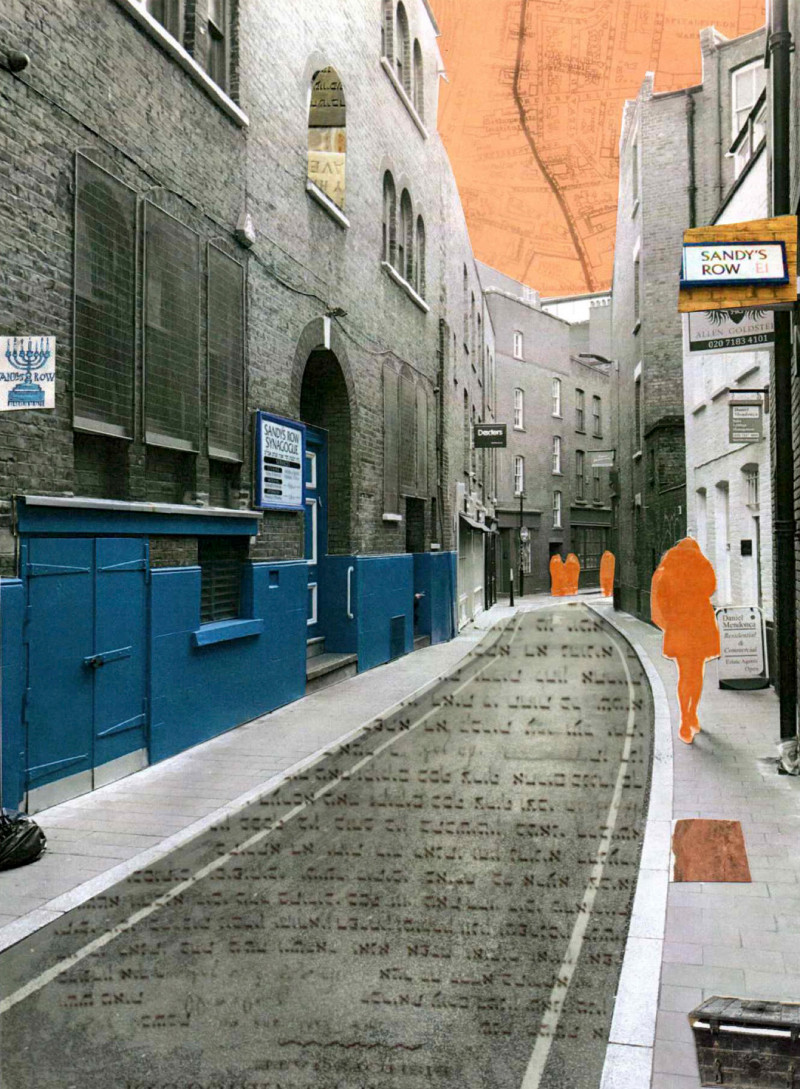

Janette Harris’ paper describes a vivid ‘live’ client-led project with Sandys Row synagogue in London that benefitted from the integration of a strong interlocutor in writer Rachel Lichtenstein. This 1st year project provided a rapid introduction to project research, process and thinking that required the students to address complex layers of requirement and expectation from both a lay and design audience at the outset of their studies.

The way in which interior designers enable different experiences of spaces, interpretations of stories and the realignment of an interior’s use are evident here.

In the city there is a required oscillation between the intimate engagement of objects, people and space to those more scoping, anticipatory interventions that reveal ways of inhabiting the city, of realigning buildings’ use and form to accommodate new programmes and experience.

These different scales of thinking are familiar processes. But the prospective value, for students and Interior Designers, is to pursue the recognition that our contribution and responsibilities are beyond a project’s immediate domain. Life inside the city requires, and we must seek to provide, a civic generosity, engaging socialised conditions that are responsive to individual and collective contemporary spatial needs.

The city is more and more an internally focused experience offering controlled, secure, fragrant, user-focused places of spectacle; or technologically managed, functionally driven environments that incorporate an interplay of programme and activity.

In her paper, Nerea Feliz emphasises her studio’s engagement of how new typologies were introduced to the power and presence of public and semi-public interior spaces in Austin, Texas. In working with students at different levels, and from different disciplines, priorities and approaches were tested. This programme exposed students to the expectations of different participants in the spaces – shoppers, tourists, retailers – and the interpretation of different, evolving and perhaps conflicting typologies and the impact these have.

The nature of how design responds to a more complex, diverse and information-saturated clientele raises different challenges - concerning both the use and reading of spaces, whether using brands in a mall or images in a guide book. The designer’s role in clarifying and reimagining this language is fascinatingly described in Colin Priest’s ‘Ways of Finding’ essay.

Working with students from another culture as well as other disciplines requires a disassembling and reassembling of tools and knowledge. The collaborative learning that is described here identifies how this consequently informs new ideas and approaches in practice.

Interior designers have a particular capability to collaborate, to draw together diverse elements and recompose these as a cohesive response to a client or site. But perhaps there is a greater responsibility. The civic expectation of interior spaces, whether public or private, and the reciprocity of their contribution to the city remains a challenge. The designer’s knowledge and actions are key to this. The application of theoretical and historical knowledge to establish a spatial presence of mind, to engage precedent and recognise a greater responsibility to the city in spaces we produce is key.

Interior designers and architects are familiar with the use of casually dialectical pairs – inside-outside, public-private, solid-void – to distinguish an idea. These are familiar terms that anticipate or even presume a relationship, but these are rooted in a concept of the interior as abstract architectural space. Interesting as this is, it is a construct that consciously avoids inhabitation, the social context, the most dynamic condition of the interior and of the city.

Inside the City holds an ambition that interior designers are recognised for their capacity to choreograph the interior experience of the city at different scales and with different contributors; as a component of the urban realm whilst curating the haptic qualities of an object or material in its composition. The ambition of the conference and the evidence of the projects described here anticipate a more articulated condition, one which considers the interconnectedness of social actions, places and things with and within the interior, the building and the city.

Andrew Stone

November 2018