The seen and unseen interior: how reflective practice enabled a live project with Sandys Row Synagogue, London

ShareThis paper reflects on an approach to a live project undertaken for Sandys Row Synagogue by 1st Year interior students, and how collaborative conditions were created between students and client to enable proposals for the development of the Synagogue’s basement into a cultural heritage museum/educational and event space. The outcomes reveal how the cultural, personal and building history can be revealed and interpreted, through ‘living’ and ‘situated’ practice. This project was tutored by Janette Harris, Kaye Newman, Suzanne Smeeth-Pouras and Karl Harris.

Introduction

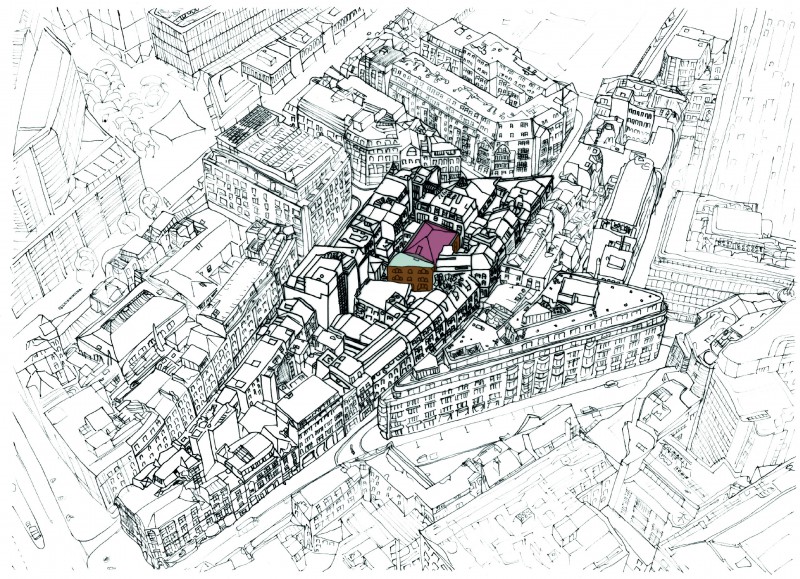

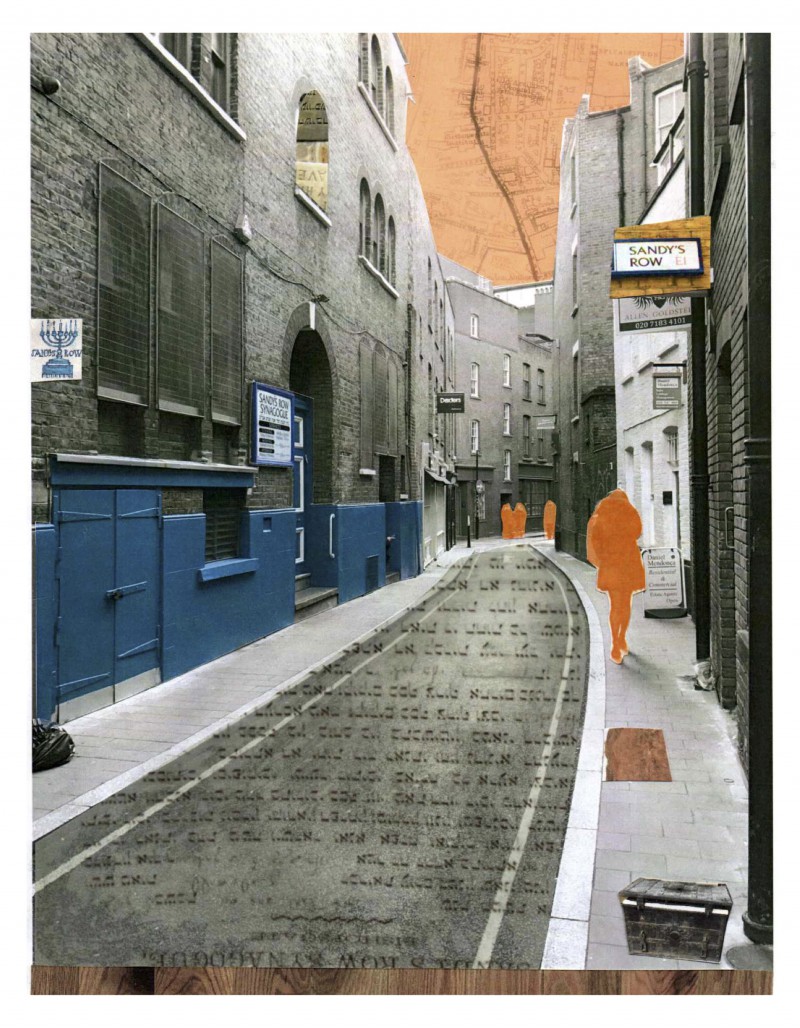

At the beginning of the 2017-18 academic year, the CASS Projects office and year 1 Interiors were invited to propose a brief to convert the basement of Sandys Row Synagogue, the oldest surviving Ashkenazi Synagogue in the UK. It is located in Sandys Row, Spitalfields, London, on the boundary of Tower Hamlets and the City. [Figures 1 & 2]

This synagogue, similar to many places of communal worship, is looking towards diversifying its premises to allow for private, semi-private and public space for a multitude of reasons, but with an underlying resolve to secure the future, for their community and site. In recent years, archivist, artist and writer Rachel Lichtenstein with Harvey Rifkind, director of the Synagogue, have researched how to breathe new life into the disused basement and celebrate the diversity and rich cultural historical context and building history. This work has included applications to the Heritage Lottery fund.

The project, the students’ major piece of work, was conceived as lasting 15 weeks. Given the ambition and potential of the project, a learning and teaching strategy needed to be carefully devised to enable student engagement and skills development, while fulfilling the brief and our commitment to the Synagogue to produce viable schemes. How could the tutors create meaningful tasks to encourage reflection, action and speculation when researching area and site, while embracing the client’s brief?

Process and practice

In recent years, Cass interiors Level 4 (1st year) students have been developing a programme that includes live projects and connection to industry. Within the projects it has become clear that reflective practice is an essential and dynamic creative tool that can promote depth and breadth, develop creativity and enable students to analyse space and its context - to understand the ‘seen’ and the ‘unseen interior’.

However, the introduction of reflective analysis can leave students feeling as if the task is a barrier, rather than using it as a tool, a means of immersion, enquiry and speculation. Many students may have experienced reflection and evaluation as a summative exercise only; however, research at the start of the process is essential given the sensitivity of the site and the complexity and transitional nature of the area. Three distinctive areas of approach were implemented:

- Investigation/Enquiry

- Secondary research starts to inform and underpin before the primary experience. - Immersion

- Dynamic action where by primary and secondary research becomes the basis for the project;

- Experience is key to reflection actions and speculation;

- Events, research, walking research, primary and secondary research. - Evaluation of experienced

- Events, research, walking, primary and secondary;

- Further enquiry through making, drawing, leading to actions, questions and speculation to enable concept testing and development;

- Reiteration leading to a deeper understanding.

Investigation and Enquiry

The design of the learning and teaching approaches, to enhance “investigation”, “immersion” and “evaluation”, asked students to form communities of practice. This “situated learning” after Lave and Wenger (1991)[1] and “living practice” after Higgs et al (2011)[2] encouraged students to share and discuss initial research into the historical, political and cultural contexts of the Spitalfields area, the Synagogue and the building. This approach helps to discourage surface learning and encourage the initial research to be a launch pad for deeper and broader understanding, while encouraging the student voice. Once the students found an interest or position, they could undertake their own path of development and discovery; their conclusion and findings were demonstrated as individual outcomes. To document and enable reflection, action and speculation, a week-by-week practice journal became the key document. The journal acted as the vehicle to demonstrate and test thoughts, actions and decisions, enabling the student to speculate through drawings and diagrams, evidencing their process and practice. It further encouraged and developed communication skills, to give the students their own voice. The challenge was to ensure the journal was used as a tool while the immersive investigation was taking place, avoiding retrospective entries.

Immersion

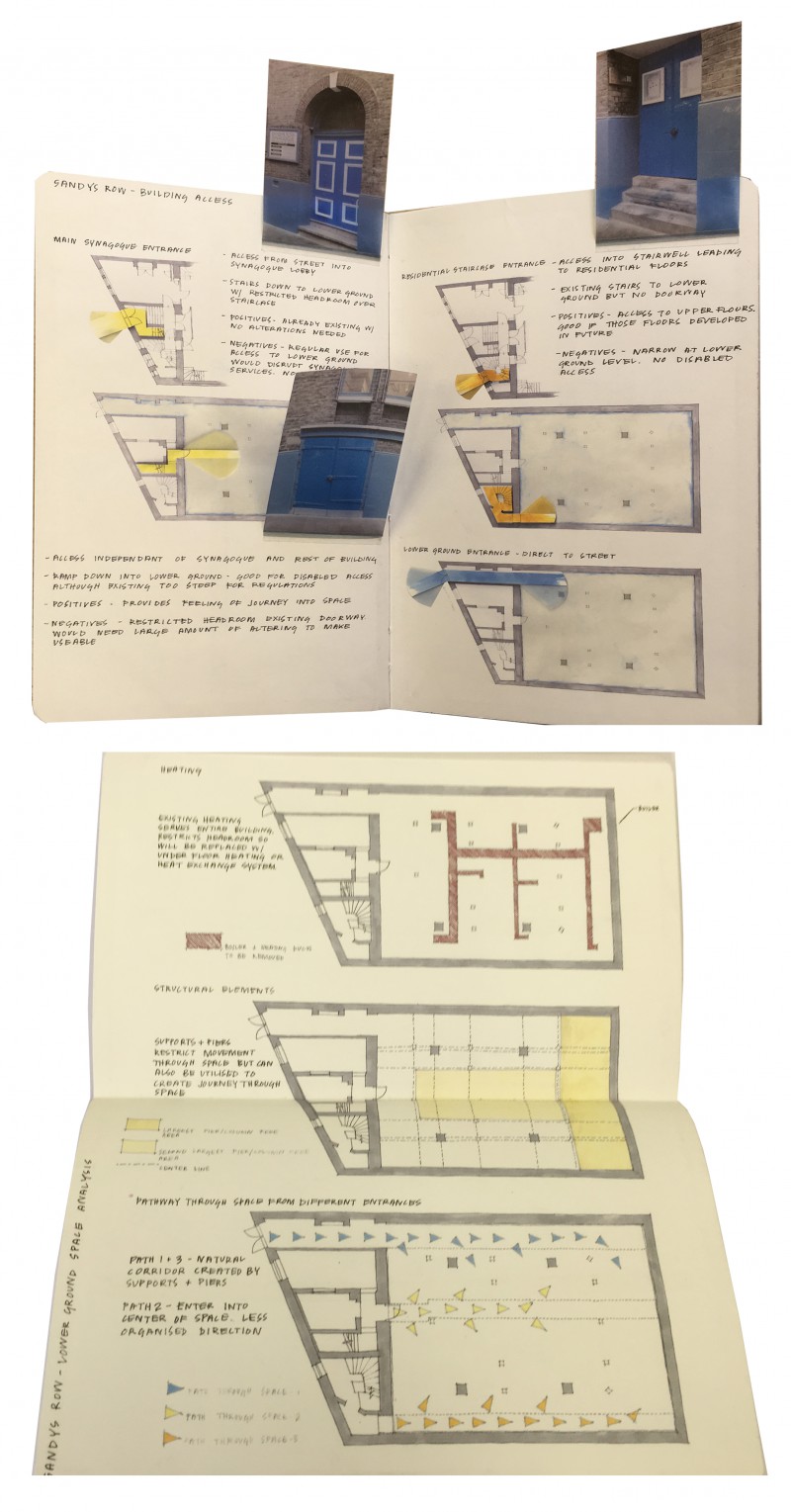

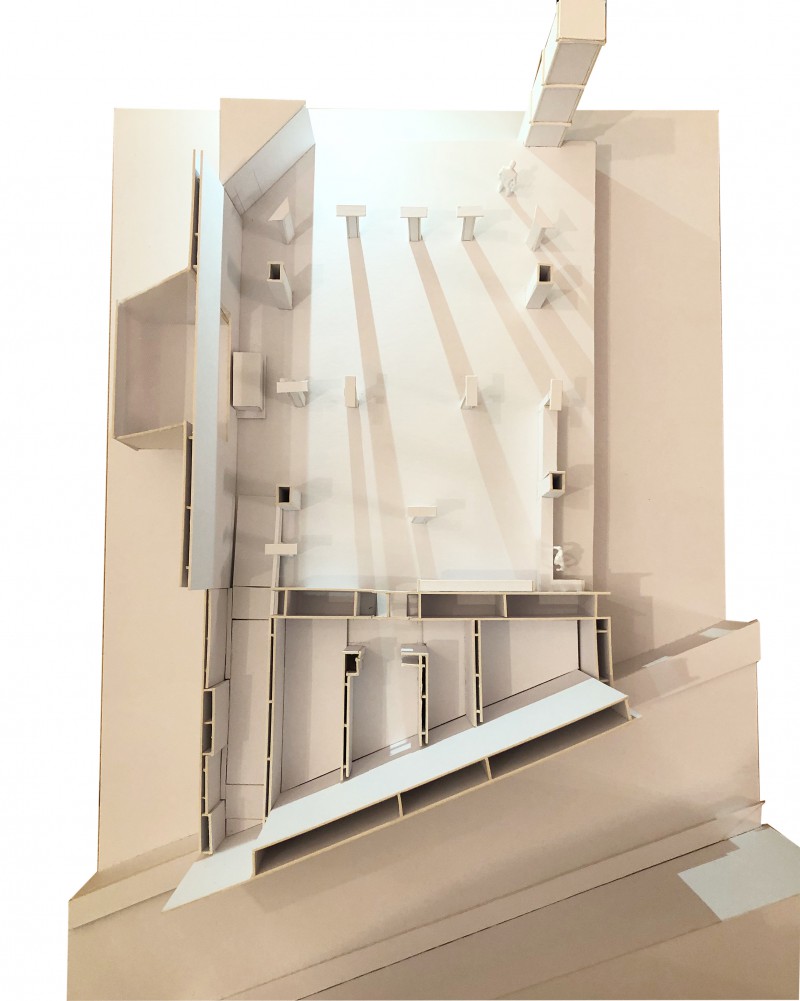

Grade II listed oak columns and four more recent brick piers support the beams to the exposed ceiling, interrupted by the lagged heating system that asks us to duck and bend our heads to navigate around the space. A crumbling, uneven concrete floor is punctuated occasionally with embedded old buttons and other small items, a legacy from when the market stall holders of Petticoat Lane stored their wares overnight. In the beams, nails and chalk writing are further reminders of this connection, as well as the ramp that allowed easy access for the stall holders from the street into the basement. The challenge posed by the client was how, through research and reflection, could the integrity of the space be maintained, embracing these palimpsests and materiality.

One of the first exercises on site was for students to individually voice-record the environmental, sensory and emotional impact of the space, on experiencing it for the first time. These initial impressions and observations were later used as an underpinning for observational drawing, photographic and measured surveys (the latter being a group exercise). These reflections were edited and recorded within the journals [Figure 6]; images were used to support findings, questions and suggest future approaches.

“It felt strange talking to myself walking around the space. But later I realised that I would have forgotten that first experience of the basement, the warmth and sense of history… Later when I talked to my friends they all had different experiences,” reported one student.

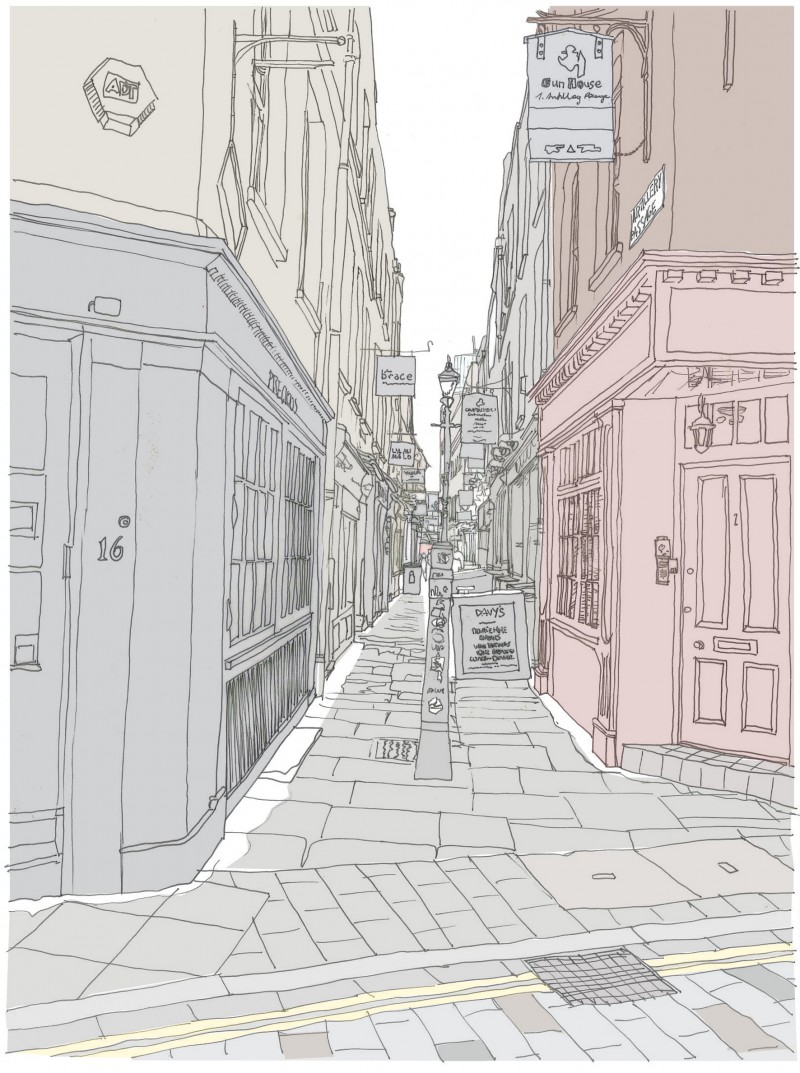

To provide support and structure to the programme of learning a series of talks and walks by Rachel Lichtenstein and Harvey Rifkind were arranged [Figs 7-9], coupled with site and area drawing sessions with tutors. We were very fortunate that we could visit on several occasions, while the investment of time and knowledge from Rachel and Harvey revealed ‘unseen’ research and understanding that could not have been sourced using secondary resources. The students’ response to this approach was incredibly positive, as the quotations from two students below testifies:

“The walking tour given by Rachel Lichtenstein has been a brilliant source of inspiration for our project based at Sandys Row Synagogue. Part of the brief is to involve the history and demographics of the local area into the cultural space that we design. As much as you can learn from researching and reading there is nothing like hearing someone who is passionate on a subject talk about it. Rachel showed us the area of Spitalfields, Aldgate and Whitechapel as she has experienced it watching it change over decades as she carries out her work as a social historian. Hearing the stories behind the buildings and streets was exciting and meant you can start to imagine how the area might have been different to what we see today”.

“As Rachel Lichtenstein is a social historian and artist, her expertise and knowledge helped us in a better understanding of the area through walking tours and discovering what life looked like before, during and after the synagogue’s golden age. In addition, Sandys Row’s president, Harvey, offered an insight into Judaism that made us all more aware of its fundamental ideas and traditions and which in turn made it possible to offer design proposals considerate of the day-to-day life at the synagogue.”

Further visits were arranged to the Bishopsgate Institute, where Lichtenstein is establishing the synagogue’s archive, for the students to further primary research to develop into meaningful concepts connected to personal histories of the local community. Once again, the students found the exercise to be useful and a source of inspiration for their design work.

Evaluation

Conclusion

The decision to place such a great emphasis on the research for this project, employing ‘living’ and ‘situated’ practice to immerse students into a live project to reveal hidden conditions, proved very successful from both a student and client perspective, as the following comments illustrate:

“The Sandys Row project has been an incredible opportunity to have an insight into the real world of interior design. It let us experience how a client’s briefing could look in the future and how creative constraints can actually work in our favour.” Student AJ.

“This project for Sandys Row was one that pushed me to grow as a designer. Getting the opportunity to work on a live project with such dedicated and knowledgeable patrons of the Synagogue is something that has helped me to build a strong foundation for my future studies and career.” Student MP.

“I just wanted to write and let you know how utterly delighted Sandys Row Synagogue are with the truly exemplary work produced by the interior design students relating to the basement project at the synagogue… Today they bought some of the students back to the synagogue to present their work in situ and I am so very impressed. The concepts, production and quality of the work is of an extremely high standard and we would very much like, with the students and the Cass’s permission, to publish some of their collages and drawings in a forthcoming publication and potentially take elements of this ideas forward for our HLF capital works project. It has been a really productive collaboration so far and we very much hope to continue this ongoing relationship with Cass.” Rachel Lichtenstein

The outcomes [Figures 14-16] are a testament of hard work and dedication of the students, who have invested in the client wholeheartedly with the ambition of the project becoming real. The next step is for the Synagogue to choose elements from the projects they would like to pursue and for a group of students to package that up into a proposal.