Ways of Finding: wayfinding in ‘Little Edo’

Abstract

The idea of the public interior[1] frames a space for civic life to perform and simultaneously challenge the experience and construction of a city image[2]. This paper narrates how undergraduate students from the UK and Japan embarked upon a series of interdisciplinary activities via two Wayfinding Summer Schools in 2017 and 2018 around the ‘Little Edo’ district in Kawagoe, Japan. Famous for its low-rise historic buildings, this collaboration was conceived as a way to emphasise the city’s vitality through its built environment and communicate the value and legacy of intangible cultural heritage to an anticipated larger international audience beyond the 2020 Olympics. Virtual and augmented realities were investigated alongside analogue practices (including interviews and peripatetic scavenger hunts) to evidence the contemporary city and its spatial processes. With the goal of designing a non-linguistic wayfinding system to help visitors navigate and orientate themselves, this complex ‘matsuri-like’ pedagogic approach offered a rich learning and teaching space in a live project context[3], enabling students to situate their learning[4]. Participating students were from the University of the Arts London - specifically Interior and Spatial Design, Chelsea College of Arts, and Graphic Design at Camberwell College of Arts - together with Human Sciences (Psychology, Sociology and Welfare) at Bunkyo Gakuin University, Tokyo.

Introduction

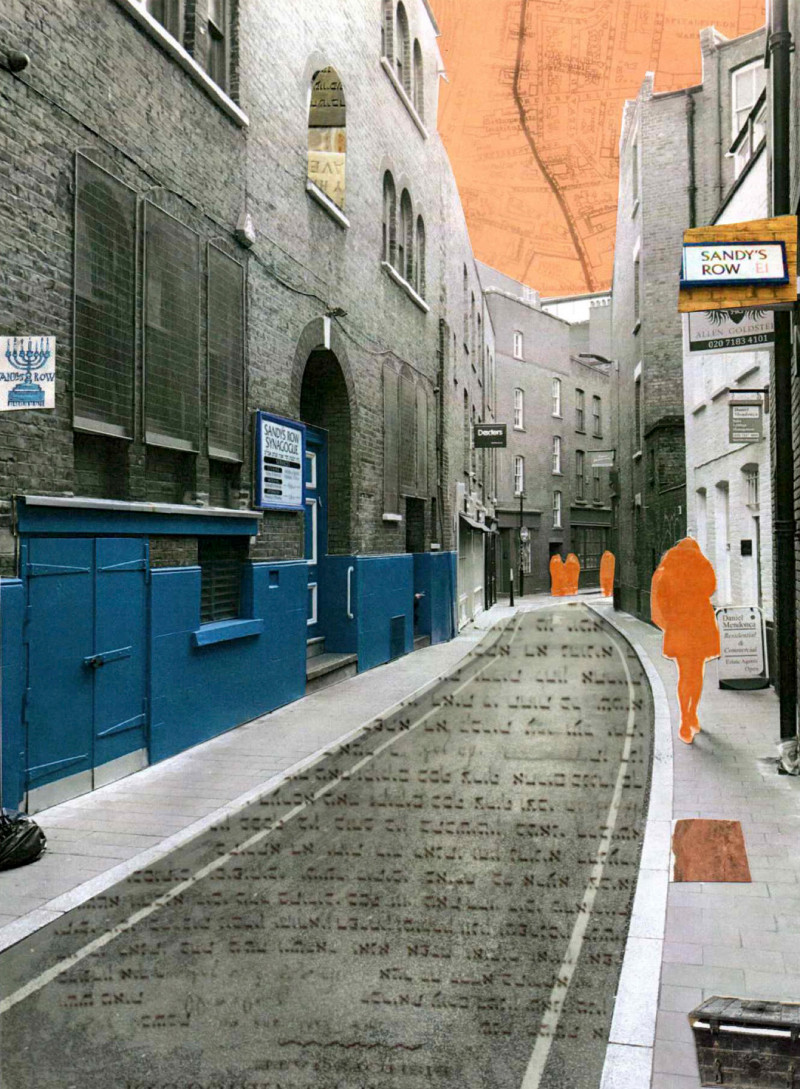

The design of a complex space and visual information system infuses the idea of wayfinding. Commonly associated with signposts, exhibitions or transport stations, this particular design practice fundamentally orients and navigates an experience of where to go that extends into everyday city life. Today the contemporary city is often framed as a nostalgic place, typically with a “historical field of vision”[5] blurring the threshold of public and private space to frame a public interior “regardless of its scale… informed and shaped by ideas”[6]. Boyer suggests in The City of Collective Memory, that “packaged environments have become vital instruments enhancing the prestige and desirability of place”[7], urging a reappraisal of our shared responsibility in the symbolisation, visualisation and gathering that Norberg-Schulz characterises as a “sense of place”[8]. Here the role of wayfinding to guide people also constructs a city image that is more than material substance, shape, texture and colour. The thinking of urbanist and theorist Kevin Lynch is instructive in this regard, where the constituent parts of the city, landmarks, edges, paths, nodes and districts combine to provide a “visual form”[9] (figure 1). He elaborates saying “despite a few remaining puzzles, it now seems unlikely that there is any mystic ‘instinct’ of wayfinding. Rather there is a consistent use and organization of definite sensory cues from the external environment”[10].

In this way we experience the city and its collective memory, exterior and interior, past and present “superimposed on each other… [to] culminate in an experience of diversity”[11] and where “nothing is experienced by itself, but always in relation to its surroundings, the sequences of events leading up to it, the memory of past experiences”[12]. As such, finding a way demands a critical position to what has gone before and, as Boyer encourages, “we are compelled to create new memory walks through the city, new maps that help us resist and subvert the all-too-programmed and enveloping messages of our consumer culture”[13]. This encourages the exploration of the city and its interiors as a resource with fresh eyes, where other perspectives challenge spatial perceptions, socio-cultural identities and interdisciplinary boundaries.

Finding Place

Such activities are reminiscent of a Matsuri (broadly translated as a festival), a civil and religious Shintō shrine ceremony in Japan. Serving many purposes, the festival constructs a binary relationship between space and atmosphere, temporally underlining Norberg-Schultz’s note in Existence, Space and Architecture that “most […] actions comprise a spatial aspect, in the sense that the objects of orientation are distributed according to such relations as inside and outside; far away and close by; separate and united; and continuous and discontinuous”[14]. The intention was to simultaneously link the past with the present, introducing opportunities for evolution and public understanding of particular communities, intangible cultural heritage[15] and socio-cultural contexts. This format of public immersion is significant - it is both frenetic and ordered to those who are both familiar and unfamiliar with the nature of the occasion, nurturing excitement, good-will and cooperation. This directly translates to the educational atmosphere of the Wayfinding Summer School environment. Students from different disciplines were introduced via formal welcomes, spontaneous celebrations and study-based activities to different modes of thinking and acting; their collaborations mirrored the intensity and variety of festival life. Students from both institutions designed and delivered cooperative workshops that established boundaries of knowledge and understanding of the city, inside and outside the classroom and the city. This expanded upon the Design Council’s “Double Diamond” model[16] that moves from problem to solution via the four stages of “discover”, “Define”, “Develop” and “Deliver”.

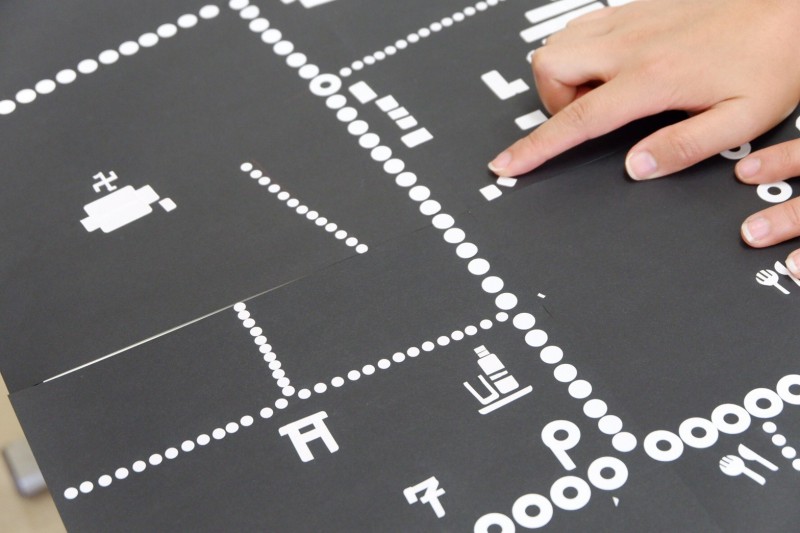

Activities deployed various forms of peripatetic practice, including “memory walks”, “scavenger hunts”, “pattern pictograms” and “colour audits”. In addition, there were interviews and demonstrations with local makers inside their shops, and inside City Hall with the Mayor and planning department to discuss conservation guidelines and planning policy. We also met inside a traditional guest house (Ryokan) and tea house for interactive workshops, while lectures and presentations inside the classroom brought together the accumulated data. The identity of the city and its interiors, through this Matsuri-like behaviour, gained momentum through the design of an interdisciplinary project brief via a common commitment to deliver a range of wares for public display in the city itself (figure 4).

Notably, in the 2018 session, the emphasis was on the design of a wayfinding product that was: for the city and about the city, underscoring the need to connect associated communities. The project thus moved from a speculative one to a mutually beneficial live project[17] that negotiated a brief, timescale, budget and product between an institution and external collaborator - in this case the city of Kawagoe.

Common Narrative

Whilst ‘Hackathons’ and ‘Idea Festivals’ are now commonplace (and some of the classroom workshops did resemble robot wars) the significant difference in this case was the necessity to maintain a meaningful relationship to the city and the experience of the city’s public interiors. Primarily due to the extreme summer weather, students worked and navigated the city’s shaded streets, interiors and air conditioning; meeting, celebrating and working through language barriers to understand how a place lives (figure 5).

Actively situating their learning, the project was conceived as a demonstration of Lave and Wenger’s theory that “learners inevitably participate in communities of practitioner and that mastery of knowledge and skills requires newcomers to move toward full participation in the sociocultural practices of a community”[18] to engage across disciplines. The programme was also enlivened by the use of augmented reality (significantly social media) connecting distant and local audiences. With both institutions using different virtual learning environments, University of the Arts students chose to display their experiences through instagram, @afterthemelodyends and @unfold.kawagoe; Bunkyo Gakuin University students used LINE, a freeware app for instant communication on electronic devices supported by the institution. In some way reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s fascination with ephemera and “shock experiences” that “enabled the spectator to think through images and to achieve a critical awareness of the present”, this image-based approach also emphasized the “frenzy of the visible”[19] noted by Boyer. However, the platforms were used in very different ways, the former a slow public story, the latter a fast collective data pool. Combined the efficiency of these sharing platforms perpetuated an unprecedented diligence and an awareness of the common narrative as students engaged simultaneously inside and outside the classroom, adding to the sense of excitement and commitment to the project as a whole (figure 6).

Over the two years, the idea of sharing has become an integral part of the programme. From spatial and graphic design students actively learning about each other’s design discipline and about human sciences in the ‘classroom’; psychology, sociology and human welfare students learning about the creative process in a ‘studio’ or ‘on-site’; to the urban scale, encouraging students to learn about the constituent identities of their own city, design and human sciences. Acts of generosity, like an impromptu visit to a construction site of a 100-year-old guesthouse (figure 7) to UAL students being invited to a family dinner, revealed the complexities of the city interior, alongside private and public life to shape social confidences and a deeper understanding of cultural differences and commonalities that contribute to a sense of place. This was highlighted by a testimonial from a participating Interior and Spatial Design student stating: “The most significant takeaway is that as designers we have an uncanny role in bridging cultures, people and philosophies, a unique power of our practice that gives us leverage to exercise positive impact, especially at the cusp of a very turbulent century.”

The variety of engagement, including physical and digital modes, scaffold a pedagogic space that is in a state of perpetual flux, highlighting Lave & Wenger’s theory about “legitimate peripherality” and how “a nexus of relations otherwise not perceived as connected”[20] echo Jonathan Meades statement in Museum without Walls, “there is no such thing as a boring place”[21]. Two years in, the city transformed visibly from one year to the next, with improved pedestrian signage and walkways and a tangible expansion of the ‘Little Edo’ district as young entrepreneurs arrive to open pop-up concessions and small traditional shops into the main commercial high street. Priced out from the conservation ‘Little Edo’ area, they are shifting the retail experience landscape by pioneering contemporary products that speak with a traditional language and are keen to explore how the city represents itself to different visiting communities. This perspective perhaps also informed the character, type and scale of the prototype products designed by the students in 2018. A composition of patterned products inspired by the textures and colours of ‘Little Edo’ architecture, students co-designed origami, tenegui (folded cloth), a solar-powered backpack, a folded chair, soft toys and seven stamp rally books with handmade symbol stamps. As a collection, the work was displayed in the city exhibition and information centres, with the public, local businesses and city mayor offering feedback and conversation about the student’s findings, proposals and exhibition design (figure 8). Different to the 2017 programme, where students designed typefaces, benches and maps, clearly suggests the changing identity between the historic and contemporary city to open up continued opportunities for the questioning of what and how wayfinding can proliferate and evolve as the city develops post-Olympics in 2020.

Conclusion

This international programme has provoked a number of collaborative relationships and opportunities, institutional and public, via a city-focused international live project. Through engagement and dialogue with external communities and city life, focusing on wayfinding adeptly encouraged the development of transferable and professional skills, socio-cultural sensitivity and confidence. The fluidity of finding a way in the city has enabled memorable and tangible identities that connect heritage and contemporary life, city and interior, through visual, spatial and human sciences that are apposite and place-centric. Enhanced through social media, physical and digital pedagogy, this matsuri-like approach enabled, as Boyer suggests, a space of “common experiences, stories integrate these into the experiences of a community of listeners; they actually structure the community”[22].