The homeless project: social agency and Interior Architecture

ShareThis paper sets out the stages (theoretical and practical) by which Interior Architecture students proposed temporary homes for homeless people, culminating in a public exhibition. The paper introduces the term “furnitecture”, and considers how designing for such a vulnerable group involves more than simply providing shelter.

The design briefs in the Interior Architecture studio at Oxford Brookes University have, in recent years, increasingly focused on socially-oriented themes. Accordingly, the Interior Architecture programme staff have refined the pedagogic sequence in the design studio, as described below, for a better integration of social awareness into the design of architecture. In our studio we foster the idea that design is a powerful resource to address community needs and, if necessary, to challenge divisive social and cultural conventions which oftentimes are reflected in the built environment.

The disciplines of Interior Architecture and Interior Design are often perceived as the superficial application of aesthetics to high-end residential projects, or as a set of skills required to install seductive qualities in retail environments. They are not perceived as fields of knowledge concerned with positively resolving fundamental human aspirations and needs within the built environment. The initial expectation of many students enrolled in our programme is to learn basic design skills that will ensure them access to a professional world, in which high-end design is the most financially rewarding outlet. For these reasons the students consider designing for vulnerable categories, for example homeless people, less relevant to their professional development. The challenge of motivating students to work on ‘social’ briefs led us to look for ways in which to instil in the students a sense of professional social-responsibility and to stimulate them to consider design objectives beyond aesthetic appearance, or superficial understanding of functionality.

Those issues have been discussed and addressed in our Interior Architecture studio through a variety of design themes, conducted over the years with the active participation of the beneficiaries of the design proposals, which in some cases have led to an actual construction. The list of socially-inspired-briefs, in which we have encountered an ever-growing set of different social situations, have included: the design and furnishing of two nurseries in Grandpont Oxford and Bognor Regis (2005/09); spatial devices for shared activities for Oxford-based co-housing communities (2014/15); the refurbishment of a local community-owned pavilion (2015/16); and the redesign of a canteen facility for an Oxford primary school (2016/17). Thus this year’s design brief, structured as a two-semester-live-project[1] with Crisis Skylight Oxford[2] continued our ongoing quest for social awareness and made use of our accumulated experience: both in its initial development in the studio, introducing the students gradually to the complexity of the issue, and in its external relations to the various key players relating to homelessness. The brief demonstrates an interdisciplinary approach, involving psychology, phenomenology, and architecture, and the importance of interior architects’ expertise to society (figure 1).

During the first two weeks, the students met with Crisis staff members and a police homeless liaison officer; both offered different and informed perspectives on the topic. This introduced the students to a variety of forms of homelessness of which they, and likely much of the general public, were not aware. These included ‘hidden homelessness’, a form of homelessness that consists of ‘couch-surfing’, through to overcrowded accommodation.[3] The first objective was not to fall into clichés about homelessness, as well as to evaluate ethical issues that may arise with direct contact with homeless people (Austin, 2016). Students were also exposed to social statistics concerning the expansion of homelessness in the UK, and specifically in Oxford,[4] as well as to the diverse underlying reasons for homelessness. After their initial discussions with Crisis, the students familiarised themselves with individual stories from Crisis database,[5] and attempted to understand how each homeless person related to the world. To facilitate this process, the students considered different connotations of house and home. It became apparent that someone can lose their house and be technically homeless but still have possessions and memories, and meaningful social interactions and/or a particular affiliation to certain places which might be un-orthodox buildings. Thus, ironically, the homeless can be said to have ‘homes’, and the students were to enable the individual cases to reconnect these inner homes with physical spaces.

The students subsequently participated in workshops which aimed to make them aware of general concepts in the discipline of Interior Architecture, such as the way people experience space as a continuous spatial field (figure 2) and the selective perception of visual/bodily stimulation, which provided valuable insights as the project progressed. The homeless project itself consisted of four stages: a) Suitcase brief; b) Support Van brief; c) Furnitecture, and; d) Final Brief.

At the culmination of the project, the students designed short-term accommodation for homeless people to be placed under the supervision of Crisis Skylight in Oxford, based on the refitting of ZED pod prototypes.[6] The academic year concluded with a public exhibition held at Crisis Oxford, attended by the press.

a. The Suitcase brief

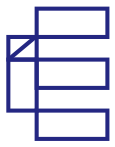

Each student was asked to modify a suitcase augmenting the spatial properties of a piece of luggage to reflect the notion of “home” for a specific homeless person. The emphasis of the exercise was on the individual: his/her social background, the circumstances that led to homelessness, the meaning of home(lessness), and the different paths that he/she was taking to integrate into mainstream society. Because a suitcase is a portable personal space that contains one’s most precious and basic objects,[7] we asked the students to find and modify suitcases that represented the individual story of their chosen homeless person – who became their client for the duration of the year’s work. Inside and around the suitcase, each student constructed a set of relationships between meaningful objects and spatial contraptions that captured the complexity of a life in a situation of crisis - the life of a homeless person (figure 3).

The use of ‘real’ suitcases allowed the students to focus on finding material qualities which they felt suited the story rather than reinventing them, thus shifting the focus from the container to its content and the ways the two intertwined (or not). The outcome presented a powerful set of narratives of homelessness; some students depicted specific moment of crisis, and others concentrated on everyday routines. The students’ final pieces were exhibited in our studio and members of Crisis Oxford’s staff were invited to review the work. It was at this point that Kate Coker, the director of Crisis Oxford, offered to exhibit the work in their city centre headquarters. This was the first time this group of students identified and acknowledged a direct relationship between design and social impact.

b. The Support Van project

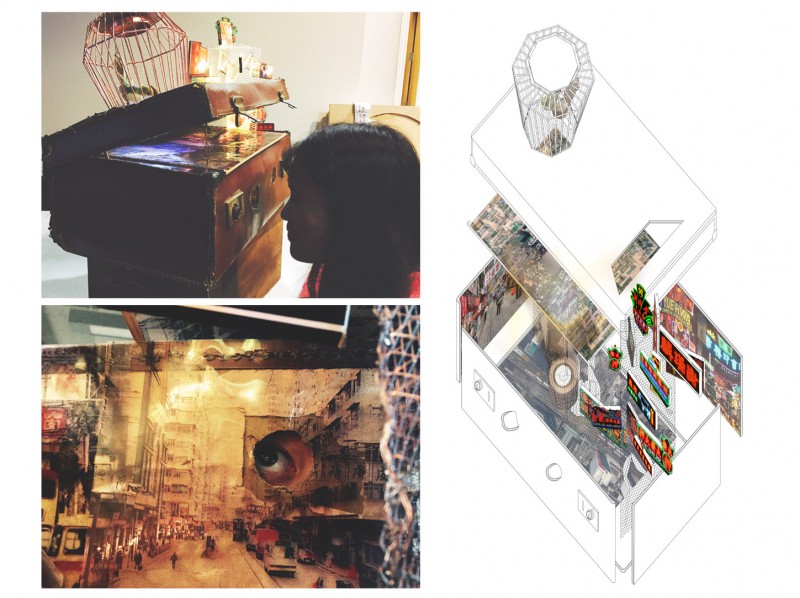

Alongside the suitcases, a more ‘practical’ second assignment addressed the understanding of the daily functional needs of a homeless person. The students were to adapt the chassis of a commercial van to become a mobile service for homeless people. The variety of designs included domestic provisions such as laundrettes, where both clothing and bodies could be washed (figure 4), meeting places and intimate spaces for encounters with friends and relatives, and services for recycling waste and produce basic commodities. The designs included work-space concepts, small enterprises to provide employment: a bakery, a plastic recycling centre, a digital carpentry that furnishes the cityscape, and a florist who grows flowers for urban spaces. Whereas the suitcase assignment helped students identify with the psychology of homelessness and reflect upon the individual’s mental space, the second assignment focused on bodily conditions, traditionally addressed in a domestic environment. Further, it considered the interaction between practical needs and human dignity, which can be compromised or damaged by the enforced exposure to the urban realm.

c. Furnitecture

Each student was tasked to build a deep frame (open-sided box) 40x40x40cm (1:10 scale of 4x4x4 metres cubic space) with durable materials and to model a series of spatial elements to allow a number of functions to take place, without necessarily sub-dividing the space into smaller units. Here it is important to note that each student had to consider what his/her person would prioritise as a need, and not to provide a range of conventional domestic furniture such as stand-alone bed and tables. To promote and encourage this mode of thinking, the students modelled first at 1:10 some pieces of furniture acting as functional props (sleep, store, sit, rest, work). They then merged them into one multi-functional spatial entity, thus creating a “furnitecture” [8] – defined as a spatial device that is larger than a piece of furniture and able to manipulate architectural space. The various functions were controlled by small ergonomic adjustments while defining meaningful portions of space. This design approach enabled students to comprehend that designed spaces are perceived as a continuous membrane (even when made of separate objects).[9] Elements of the suitcases and functional parts of the support vans were redeployed to articulate the spatial qualities of these deep-framed boxes.

d. Final Brief: Redesigning ZED Pods interiors

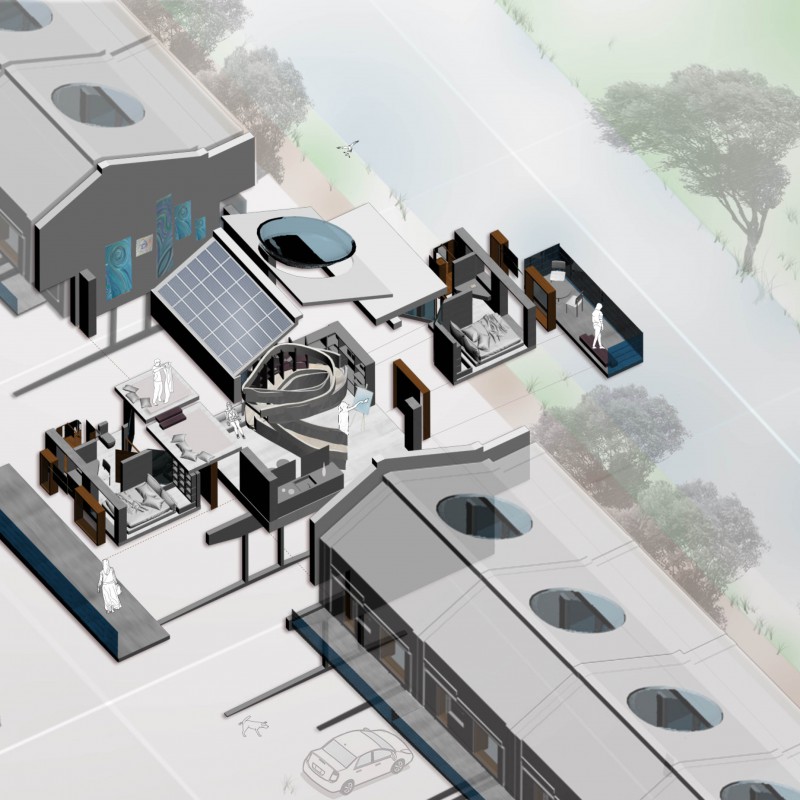

The culmination of the didactic process occurred in the last stage of the brief. The students were asked to adapt the structural frame of a ZED pod prototype, placing them on the characteristic metal props over the Nuffield car park, a site next to the Crisis building in Oxford city centre and other relevant services (job centre, train station etc.). Once the site was introduced, the studio discussion focused on the possibility of modifying an urban environment using domestic design terms, thus fostering the relationship of the pods with other services into the design process, including consideration of accessibility, visibility, proximity, comfort and dignity. Changing the students’ perception on homeless people from ‘social-outlaws’ rejected from the city-space to dwellers who perceive and use the city differently had a profound impact on the students’ design decisions. This was expressed both in functional terms (some domestic functions were designed to be provided outside the pods) and in psychological terms: homelessness need not be hidden away, degrading the city by its presence, but represents an opportunity to build a resilient and proud local community.

The elevated line of ZED pods in the Nuffield car park provided the unifying context for the final designs. The students could opt for a single pod design (to be mirrored as in English terraces), or to merge two pods for a compact co-housing solution. The internal allowance of space (smaller than in the previous furnitecture boxes) required a further process of compacting and streamlining of functions, as well as increasing overlapping and flexibility of use. All resulting designs were unique, despite being placed in identical pods. The difference reflected the process of refinements, which started with the suitcases of individual psychological considerations and spatial sequencing, and travelled through the other practical and functional steps of the assignment. Each solution was suited to specific ‘social’ groups: for example if the homeless individual had children, the pods allowed space for them to visit, or if the individual was a maker, the pod contained a small workshop area or art making space. The designs operated like an extension of the person, and so the different categories of homelessness emerged naturally.

Most importantly, the pods did not resemble small houses (figure 5). The design criteria did not require a conventional sub-division of the spaces into rooms. Instead, the pods provided a continuous spatial field that could extend into the public space with semi-permanent partitions and changes of levels to establish variable degrees of intimacy. In form and articulation, the design proposals (models and drawings) were similar to shelters or natural organic spaces that provided refuge.[10]

To conclude, the social-brief worked successfully to support the idea that the design studio can function in the role of social agent: the brief has proved its social impact via the public exhibition and media coverage that prompted public discussion. It offered alternative views and options to those currently used with little success when tackling homelessness. In the long term students learned that well-being and psychological aspects are key when attempting to rethink urban issues in the context of individual spheres of interaction. This understanding does not abandon functional requirements, but rather expands the understanding of what functions mean, and by doing so restores dignity to individuals. The students also began shaping their critical awareness and willingness to proactively engage with local and global communities via a professional prism. Student Chi Pun, for example, summarised her learning in the project: “Before this project I didn't know much about homeless, but throughout the design process I learnt that homelessness can be both physical and psychological. I developed closer feelings to homeless people and understood their struggles and needs. In my design, I reflected the features that could support them to overcome their situations."

At the students’ exhibition of models and drawings at Crisis Oxford, it was the combined psychological and practical design approach that caught public attention. Andrew Gant, Leader of Liberal Democrats on Oxford City Council, offered the following comment: “Big hostels have their problems, and new homes tend to be built out of the city centre, where people are far away from the services they need…. Obviously you would have to think carefully about the practicalities of something like this [the students’ proposals], but it is a great idea and brilliant to see young people being so involved in this issue that resonates very strongly with everyone.” Rachel Lawrence, who manages Single Rough Sleeping services for Oxford City Council, added that the work suggests a deep understanding of homelessness issues; one which takes into account the psycho-social trauma and not only the need for a “roof over the head”.