Places where I have slept

Abstract

The following paper describes a project, for both Interior Design and Architecture students, which reconsiders the hotel as “social condenser”. The project also explores regeneration and gentrification within a North American context – city centres characterised by strip malls and the car.

“Touristic time is reversible and touristic space is elastic…correspondences between time and space, between histories and geographies become negotiable.” [1] Diller+Scofidio

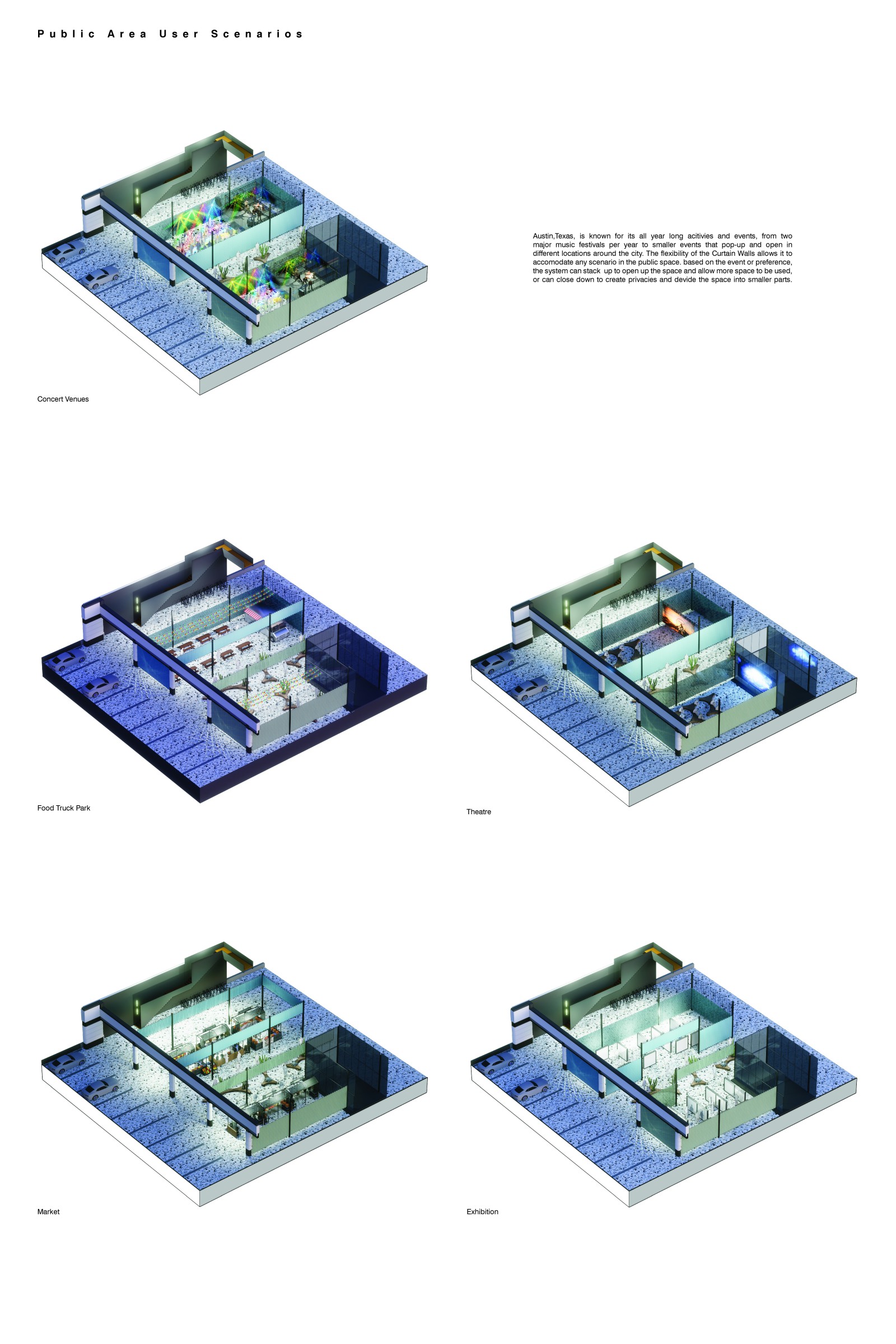

In cities largely dependent on automobile navigation - such as Austin, Texas - public gathering tends to be displaced from the public “outdoors” to the private or semi-public “indoors”. In the absence of pedestrian-friendly streets and squares, public life mostly takes place in semi-public interior spaces. An Interior Design Studio offered in the spring 2018 sought to reflect on the potential role of public interiority and temporary dwelling in the American city with a commitment to urbanity as a condition of diverse and informal conviviality among people from various socio-economic groups and cultural backgrounds. The project was to design a hotel within a vibrant strip mall located in an inner suburb of downtown Austin.

Hotels raise a number of core design issues related to branding, globalization, gentrification, and lifestyle. Airbnb has radically challenged the hospitality industry. Budget constraints and tourists in search of “authenticity” and integration within the local community have made Airbnb the choice of many travelers, altering real estate markets by increasing rental values in tourist areas, and transforming residential neighborhoods into tourist destinations. Digital platforms and social media are shaping the physical world by generating international trends and influencing global taste. International hotel chains were always generic, but as Airbnb has extended worldwide, temporary dwelling spaces in domestic interiors are, arguably, increasingly looking alike. While globalization inevitably homogenizes the built environment, the tourism industry relies on cultural identity to maintain itself. [2]The analysis of Diller + Scofidio’s projects and writings, “Suitcase Studies”, “Slow House” and “Homebodies” was used to reflect on the way that the commodification of the tourist gaze manifests in the built environment and how critical observation can be expressed through design propositions. The tension among opposing forces is at the heart of the hospitality industry: local versus global, authenticity versus familiar comfort, the appeal of uniqueness versus the influence of worldwide trends. Within this contradictory arena, students looked at hospitality as a fabricated environment where symbols, illusions, expectations, the real and the unreal combine into the traveler’s imagination.

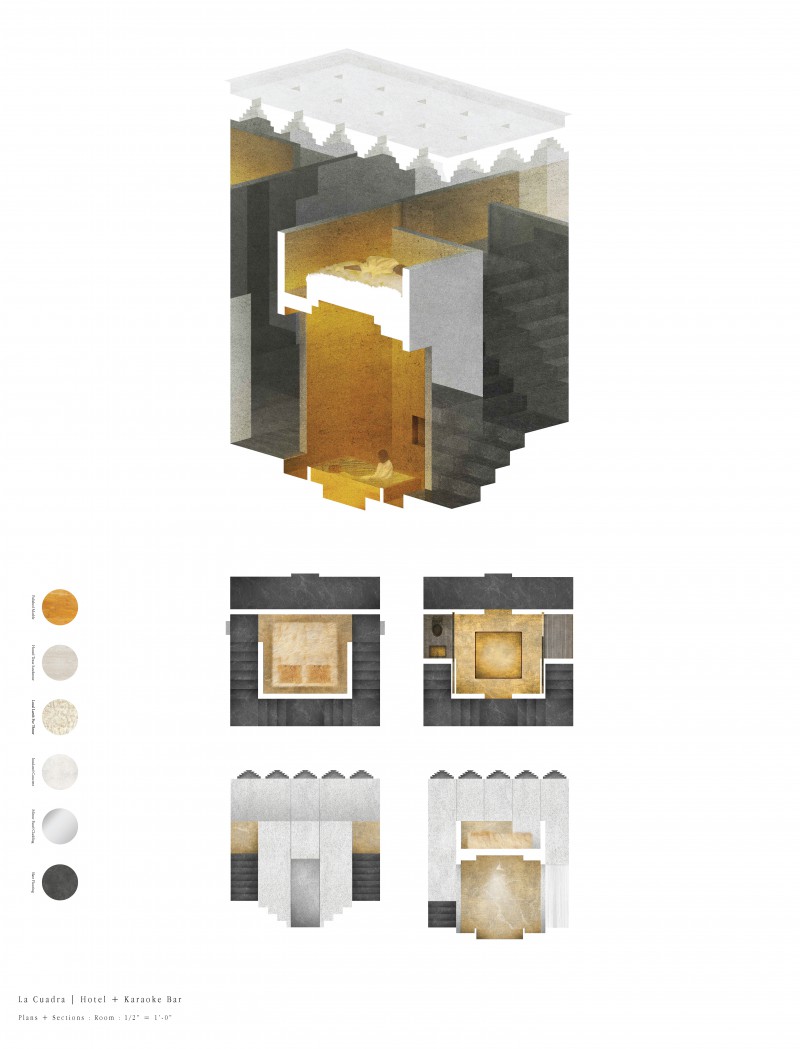

What is “authentic” anyway? Isn’t the strip mall a truly “authentic” typology? Operating within the generic realm of the strip mall typology was both a design challenge and an opportunity. The course looked at Interior Design’s capacity to transform neutral space into a time-specific cultural product. The reading of Nicolas Bourriaud’s “Postproduction, Culture as Screen Play, How Art Reprograms the World” manifesto, provided the studio’s conceptual grounds to inspire the creative appropriation and reinterpretation of existing built form. [3] In an architectural context of no context, such as the non-specific architecture of the suburban mall, students explored spatial organisations defined by the active role of interior elements such as interior surfaces and furniture. As a starting point in the semester, students were asked to consider the design of a hotel room (13’ x 18’ surface area – 3-9 x 5.5m) with a particular emphasis on the design, documentation, production, and placement of objects and surface treatments. The objective of this exercise was to explore the capacity of interior elements to inform space, and drive the generative design process. The direct relationships between the furniture/surfaces, and their impact on space, guided the design proposals. Students followed the thread of their interests to both uncover and discover new salient material and spatial conditions. Sleeping is a very intimate experience; participants in the studio aimed to create unprecedented oneiric spatial encounters with their guests resulting in long-lasting memories. Experimentation with different materials, physical models and fabrication techniques was encouraged. The outcome was a combination of material studies and spatial investigations.

“The room is the beginning of architecture. It is the place of the mind…The plan is a society of rooms,” wrote Louis Kahn.[4] On the second half of the course, participants in the studio looked at strategies of adaptability, transformation and reuse of the existing retail structure. Starting from the inside out, the room’s material and formal vocabulary was deployed and further developed to generate a society of rooms: private and public, indoor and outdoor. The advanced-level course was integrated by a total of 15 upper-level undergraduate and graduate students, from Interior Design and Architecture backgrounds (five graduate students from the Interior Design program; eight undergraduate and two graduates from the Architecture program). Students worked individually across the semester. The combination of student’s backgrounds in an interior-focused design studio was unique. Interior Design and architecture students brought different skills to the classroom. Interior Design majors were comfortable working with surfaces and furnishings and engaging materiality at a very early stage of the design process. Architecture students were more reluctant to let interior material choices and atmospheric effects drive their design decisions. After the anxiety associated with the early design exploration, there was a genuine sense of spatial discovery and collective relief. During the semester, there was a very productive exchange of skills - Interior Design students were challenged to consider the possibilities enabled by drastic manipulation of form, and architecture students discovered the capacity of surface treatments and objects to also produce radical spatial transformations.

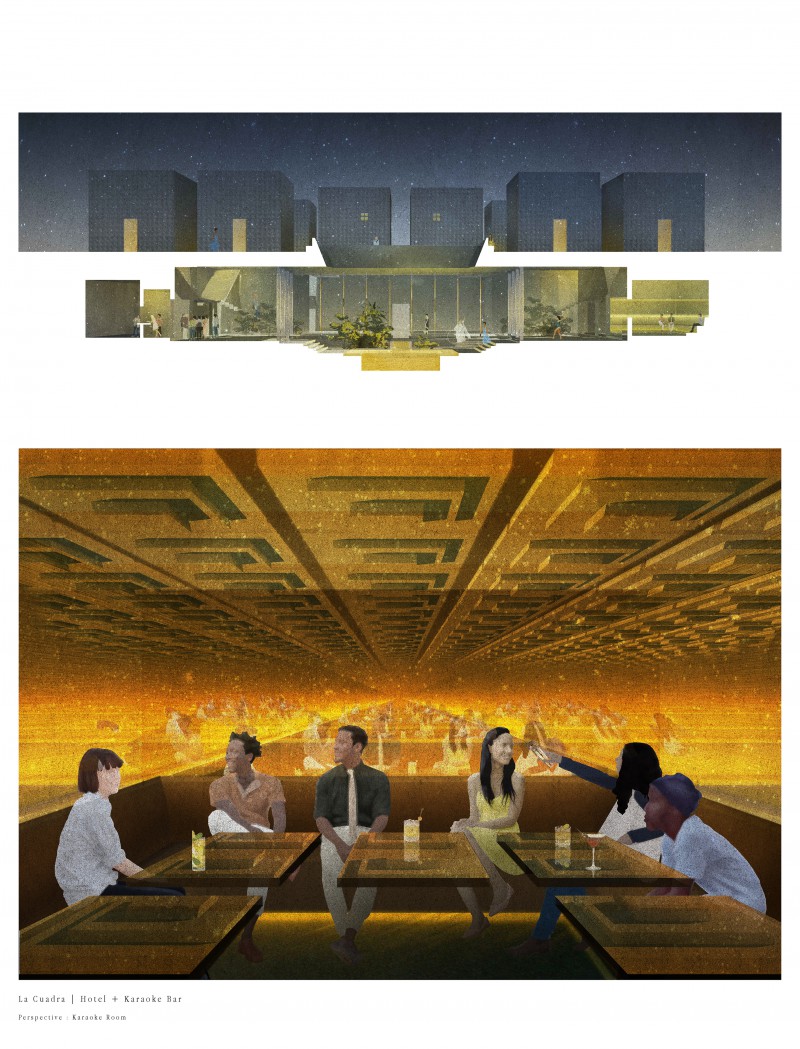

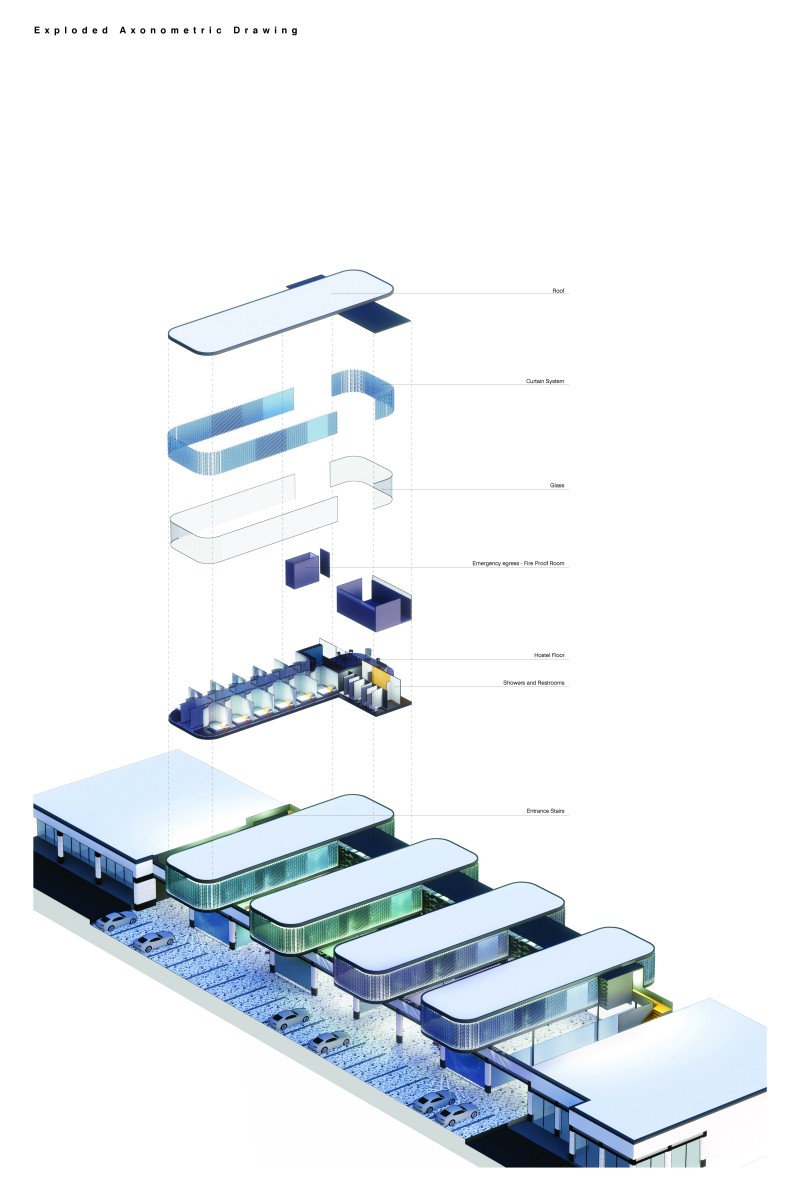

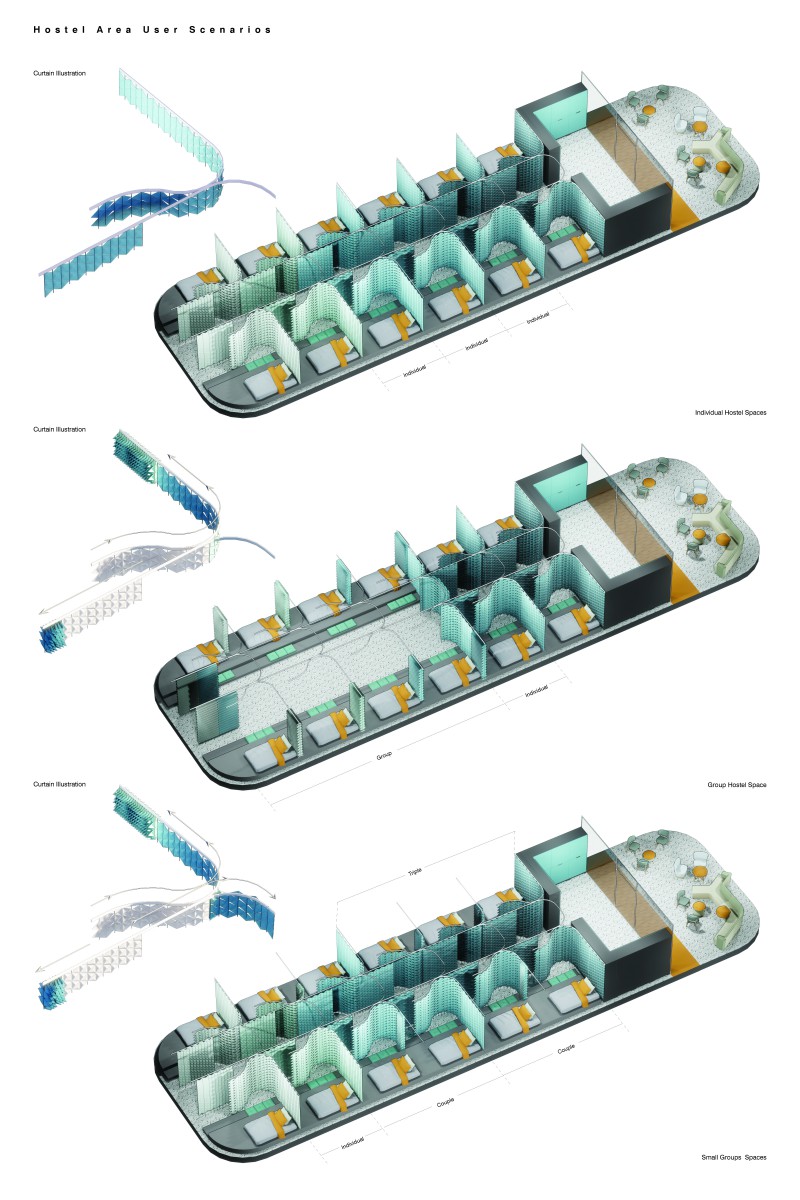

Here, two projects illustrate the studio design sequence across the semester. Architecture student Hannah Frossard proposed an elevated orthogonal grid of 24 rooms. Her room is conceived as a private sensorium with a voyeuristic scenography inspired by a close analysis of Adolf Loos’ spatial and material interior organizations. The project turns its back to the street creating an unexpected interior. The rich material palette, and the recurrent use of mirrors, make the interior space of the hotel an infinite voyeuristic condition, a rich and endless interior hidden within a banal box (Figures 1 and 2). Interior Design graduate student Georges Fares proposed a youth Glam Hostel. He invested a significant part of the semester designing a multi-functional textile screen/curtain that serves as a mutable interior partition mechanism. Four large communal rooms (12 beds each) are elevated from the ground plane. The screen allows each room to be sub-divided according to different levels of occupancy, individual travelers and groups of friends. The design of the curtain involved a digital exploration of design issues that dealt with serial variation, digitally derived patterning, and digital fabrication. The intricate and multi-faceted felt geometry of the curtain helps with noise absorption. Where conventional hotels resort to mediocre art to decorate and fill interior surfaces, the curtains’ sculptural nature make them an integral decorative element of the hostel. At the same time, the curtains transform the ordinary architecture of the strip mall by “dressing” its walls and transforming it into an extraordinary and theatrical space (Figure 3).

When considering the addition of the hotel to the existing socio-economic ecology of the strip mall, students were asked to view the hotel as a social condenser. The studio observed how, as fading commercial strip malls have declined in value, businesses owned by the immigrant population have occupied these spaces. [5] Despite the general unpopularity of this car-driven typology, in gentrified city centers such as Austin’s, ironically, the rich diversity of small business and “mom and pop stores” populating strip malls, offer residents the closest to a true “urban” experience. Within the studio site, a 116.000 sq ft strip mall in north Austin, one can take a shirt to be altered at the local tailor, wait for it to be ready while having lunch in the taqueria next door, and kill some extra time in Kikokuniya specialized Japanese bookstore. A Dollar General, a Taiwanese American supermarket chain, a revolving-belt sushi bar, a hairdresser and an H&R block, are other business occupying the lot. Within the course programmatic requirements, lodging was to be intrinsically combined with another public or semi-public program that would contribute to the strip mall’s social ecosystem, the neighborhood and the city of Austin.[6]