Lost Interiors: An investigation of the Keskidee Centre

#lost RESEARCH

Abstract

This article discusses the methodology used to investigate a building which no longer exists. The subject of the investigation was the Keskidee Centre, Britain’s first black-led arts centre, which, despite achieving international cultural significance in the late 1970s and being chosen as the location for Bob Marley’s ‘Is this Love?’ music video, is relatively unknown and little published information exists. The investigation utilised primary sources including archive material and interviews to reconstruct the Keskidee Centre through text.

At approximately 9:30pm on Thursday 8th March 2012, about 40 firefighters began tackling a fire at Christ Apostolic Church in Islington.[1] The fire began at the building’s ground floor and spread through its four-storeys to its roof so that ultimately, the damage was too severe for the building to be repaired and the remaining structure was demolished, [Figure 1: Dilapidated remains of the Keskidee Centre]. The cause of the fire was never determined.

The Keskidee Centre, named after a Guyanese songbird, began simply as a community centre for local young black people but its cultural impact would come to define its legacy as the Centre contributed to the successful careers of black arts icons, including dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson and composer and Kora player Tunde Jegede.[4] The Keskidee’s theatre programme also achieved international acclaim in its own right and within a decade of opening, its success attracted Jamaican reggae musician Bob Marley to choose the Keskidee as the location for his ‘Is this Love?’ music video in 1978. However, financial challenges afflicted the Keskidee throughout the 1980s forcing it to close permanently in 1992.[5]

Methods of investigation

The object of my study no longer exists, making it an unusual subject for an architectural investigation. Architects are used to understanding a space primarily by being in it, or by reviewing hundreds of photographs, detailed plans and physical or computer-generated models, resources which do not exist for the Keskidee. Often, we will read about others’ experience of being in the place when we cannot visit ourselves. Unfortunately, the Keskidee Centre is lost in these traditional methods of investigation as there are few published works which discuss it. To date, press and academic work have focused on Keskidee as a theatre and music venue, overlooking its primary purpose as a cultural and community centre.[6] My investigation aimed to reframe the Centre in an architectural light and consider the importance of the building itself in enabling this creativity and the affordances it provided those who used it.

Without the ability to visit the building or read about those who had, the adopted methodology was an architectural investigation to connect clues identified in archives with information gathered in interviews to reconstruct an image of the Keskidee Centre. The Centre was part of a crucial network of people who supported the diasporic community, including John La Rose and Jessica and Eric Huntley who established the archives of the George Padmore Institute and the Huntley Family Archives respectively, from which much of my research was completed. The decision about what to store in archives is as much a reflection of what we value as a society as the content itself. It is important that both the George Padmore Institute and the Huntley Archives were collated by those it concerned, making them especially valuable resources for investigating an otherwise neglected aspect of recent social history.

The George Padmore Institute is an archive, educational resource and research centre connected to New Beacon Books in Stroud Green, North London, holding documents about Britain’s community of Caribbean, African and Asian descent. [7] It contains details about activist groups and cultural activities which took place at the Keskidee Centre. The Huntley Archive was deposited at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) in 2005 and contains documents, including legal and marketing material which the Huntley family retained after the closure of the Keskidee. [8] The third archive I used was Islington Local History Centre, which holds Islington’s historic maps and directories and also held an exhibition titled ‘The Keskidee. A community that discovered itself’ in 2009. [9] I was also able to find some architectural information at Historic England’s archive. My research benefited greatly from oral historian Alan Dein’s recorded interviews with actors and young people who had occupied the Keskidee.[10] The former users described the activities that took place and their feelings regarding the importance of the Keskidee. Through their descriptions, the interviewees unintentionally described the spaces they had once occupied.

Piecing archive clues together

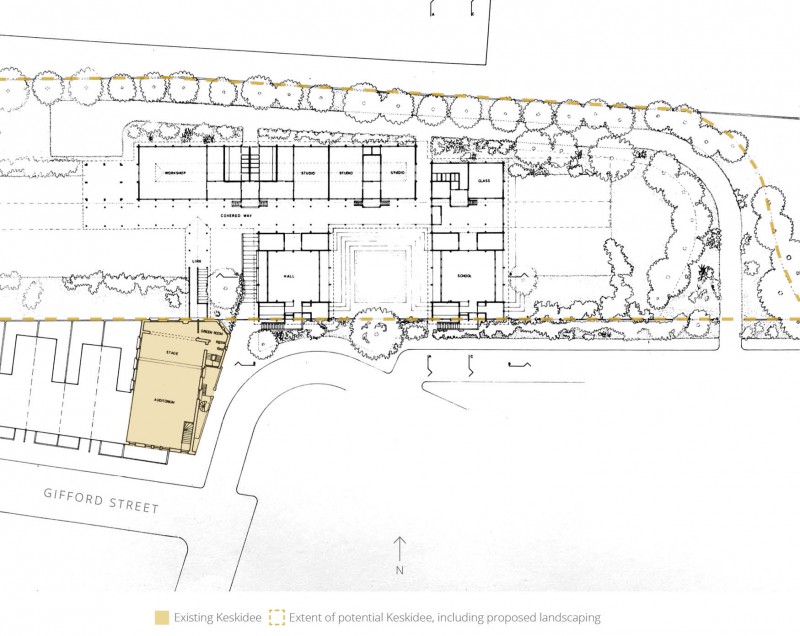

The Keskidee Centre was very much an architecture of programme. At LMA, I found an advertising leaflet produced by the Keskidee Trust which described the spaces of the building when purchased, ‘a large and a small hall plus four sizeable rooms and a kitchen’.[11] Abrams recognised that the various large rooms of the Keskidee could be easily reconfigured to suit the needs of the local black community, who were prioritised in the building’s adaptive reuse. It was important for me to find as much information about the building’s alterations to be able date the changes and understand their relationship with Keskidee’s timeline of success to determine any impact.

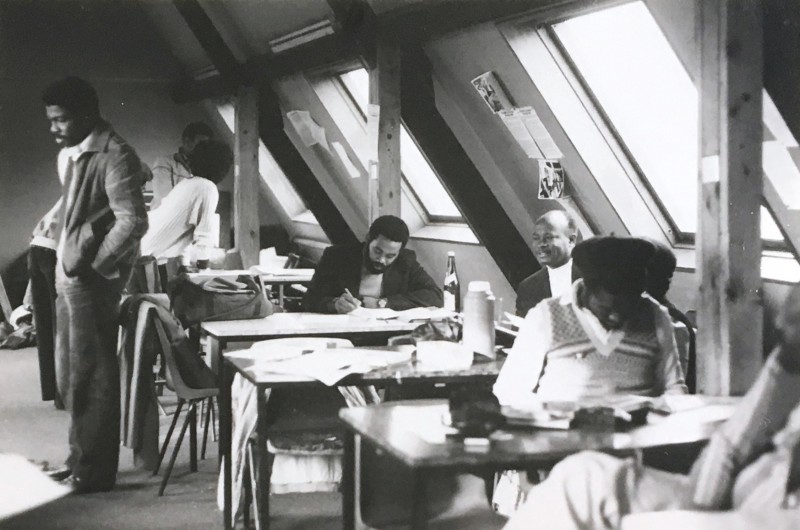

I compared a Historic England report to an ‘Existing Plan’ dated 1975, from the Huntley Archives and concluded that Abrams had inserted two upper floors.[12] The newly created upper room displayed the Victorian Mission Hall’s exposed roof timbers, where the rafters were described as having a ‘very high collar’[13] and were ‘mitred at the top with no ridge beam’.[14] Photographs I discovered at the George Padmore Institute supported this finding and showed how the room was used, [Figures 3-4: The attic room in use for a Black Parents Movement meeting]. Abrams installed skylights into the slated roof and a semi-circular window on the south façade[15] which flooded the upper space with light. These alterations made this attic interior particularly well-suited for reading and so it became the Keskidee’s library, with Linton Kwesi Johnson as the centre’s librarian.

The significance of this window installation would not have been obvious at the time, however Abrams’ ability to visualise how design can unlock the function of a space in this instance had profound implications. It was in this room that Johnson developed his unique work which led to him being credited as the inventor of dub poetry,[16] giving him worldwide success and showing that through alteration and reuse the centre could contribute to society in ways not possible before.

Constructing a vision of the Keskidee Centre through memory and interview

This research is framed in the context of a period of important social history which is, significantly, still in living memory and so is subject to multiple, often conflicting, interpretations. The limitations of memory were clear when I contacted Peter Bell to discuss the project which he had worked on relatively briefly a long time ago as I used his own plans I found at LMA to aid his recollection. I also interviewed Norma Ashe, co-founding trustee of the Keskidee Centre. Ashe did not remember Abrams discussing his idea for a much larger Keskidee Centre with her, but she was able to provide significant understanding of Abrams’ character, praising his selflessness, work ethic and determination. On the other hand, Bell had met Abrams only a handful of times and so was much more removed from the emotional implications of the project but he provided technical information about the building I was unable to find elsewhere. The interview methodology was key to reconstructing the building, and so memories have been fundamental to the outcome of my investigation, but are inherently imperfect, incomplete and subjective.

Conclusion

Research for my investigative work on the Keskidee Centre has been predominantly from primary sources. I have relied on my architectural skills to recreate the Keskidee from the dilapidated remains of the end-of-terrace building where possible. An ability to interpret found architectural information and to imagine space helps to understand our lost buildings. Archive material led me to conduct interviews and listen to recorded conversations about the building, therefore undertaking an ethnographic study to immerse myself in the feeling of the building throughout its life.

For others undertaking an architectural investigation, it may be elucidating to start with secondary sources to gain a general understanding of the research topic, which could be online articles and newspapers or other material found in a university library. A next step would be to pursue primary sources which is time consuming but you discover valuable content which may not appear in secondary sources. Some primary sources may be found at national archives, such as those at Kew and Historic England. Local archives can provide more detail. It is important to consider the provenance of the archive material and search for information donated by primary users if available. It is possible that local councils will store pertinent material, perhaps in the directories of a local library. Locating primary sources may lead you to potential interviewees such as architects, from architectural drawings, and building’s trustees, from legal or marketing documents.

My investigatory work was rewarding as conducting interviews and exploring archives has led me to unexpected discoveries. Studying the Keskidee Centre has given me a greater appreciation of the significance of impression, memory and feeling in determining a lost building’s legacy.