In a Darkened Room: reflecting on the negated interior

ShareThis paper explores the idea of the photograph as both revealing and concealing of its own interior origins, asking whether the camera obscura’s interiority is useful in understanding changes in our relationship with the city. I explore exterior/inner/interior interactions, firstly from the subjective, bodily experience of a camera obscura in Tavira Portugal; a detached and voyeuristic view which renders the outside close yet strangely distant. Secondly, by juxtaposing the camera obscura with Rachel Whiteread’s Water Tower, I examine the paradox of an interior which, in changing the way the city is viewed, has simultaneously contributed to its own hiddenness.

Introduction

Design: Culture and Society is a three-year history and theory programme at the University of Central Lancashire, aimed at giving students of Interior and Product Design and Visual Communications a critical approach to design. Starting from spaces and objects, projects explore intersections between different disciplinary contexts. As an interior designer and educator, I have developed the programme to show how the interior in a broad sense can inform multiple disciplinary fields.

In this instance, interior is explored through its connection with the photographic image, examining how spatial engagement with the city through the camera obscura enabled a distancing between subject and object that led to the interior being negated, subsumed into the image itself.

A version of this paper was delivered to second year design students and formed the basis of seminar discussions about the dominance of the image in the modern city.

A Tale of Two Towers

There is another disused water tower whose interior marks a changing view of the city. This tank, high above the streets of Soho in New York, was cast by artist Rachel Whiteread as a double of its own interior, revealing more than just the negated volume of its hidden chamber. The tank was once part of a high level urban landscape, that together with other similar structures, formed part of a system that supplied the city below. By inverting the space of the tank in translucent resin, Whiteread recalls memories of the people it once served; a ghostly presence cast in light against the bright sky.[1]

These two water towers have been remade to contain and reveal aspects of the city through their own interiors. Each one carries in its essential interior condition a link between the observer and city, outer world and inner thought. In both conditions, the interior plays a dual role of concealment and revealing. As both physical and metaphorical space, the interior reveals the city, whilst obscuring itself.

There is an uncanny quality to both examples that, in their doubling of the interior, recalls the Surrealist claim that the city could be changed by changing the way we look at it. Finding strange and disquieting qualities in everyday settings, the Surrealist project was to find new ways to look at the world by opening routes to the unconscious. In that quest, the interior often features, not only as the location of the familiar and the uncanny, but also as a spatial metaphor linking the outer world and the inner mind.

The ability of photographs to capture atmosphere was discussed by Walter Benjamin, who noted the eerie qualities of emptied spaces, doors and passages in Eugene Atget’s photographs of Paris. Benjamin saw a strange emptiness in these pictures that went beyond the rational, documentary capabilities of the medium and into the subject’s memories[2], a projection of inner thoughts onto the photographic image that connects to a sense of interiority.

From Darkness to Light

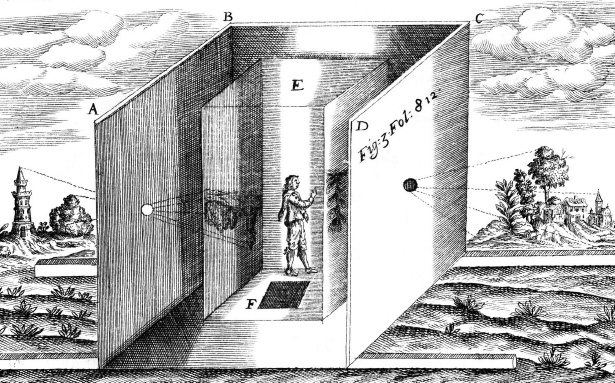

The camera obscura also became a useful model in the early nineteenth century for explaining how the human visual apparatus was believed to work, such that it became a paradigm for understanding the eye and the importance of the sense of vision. Jonathan Crary locates a key shift in the status of the observer in the Cartesian separation of mind and body in which vision was believed to be the primary sense for receiving information from the outside world [3][Figure 4]. As an explanatory model for the way the human eye works, the camera obscura became significant not only for helping to explain the sense of vision, but also as a metaphor for connection between the mind and the outside world, representing, as Crary puts it, ‘… the most rational possibilities of a perceiver within the increasingly dynamic disorder of the world on which human knowledge is based, mediating the outside world with the inner mind.’ [4]

There is something reassuring about the use of an historic model as metaphor for unfamiliar, contemporary phenomena. In the rapidly expanding city of the nineteenth century, for example, the camera obscura’s comforting enclosure presented a useful analogy for commentators to discuss public anxiety about the complexities of urban life. In Pierce Egan’s 1821 account of London life, Life in London, the author uses the idea of camera obscura as a metaphor for framing the city, a trope through which to view the city’s dangers from a detached and safe place.[5] [Figure 5]

‘The author has chosen for his readers a Camera Obscura view of London, not only from its safety, but because it is so snug, and also possesses the invaluable advantage of seeing and not being seen.’ [6]

Beyond its function as a visual apparatus, the camera obscura’s view from interior to external world provided a device for the writer and reader to imagine life in the city. To observe in this way depended on the body’s presence, mediated by the interior space of the camera, to create a distance between subject and object. The voyeuristic relationship represented in Egan’s account showed how the interior viewpoint of the device provided a view of the city, in which the position of the observer was recognised, separate and unseen.

From an interior perspective, the darkened room can be seen as more than a means to view the outside world; it also presents a re-ordering of the relationship between viewer and viewed world, where the observer is simultaneously isolated from the outside world, whilst remaining visually connected. As Crary puts it, ‘an observer is isolated, enclosed and autonomous within (the camera obscura’s) dark confines, it is thus inseparable from a certain metaphysic of interiority.’[7]

Although the camera obscura provided a useful model to illustrate this shift in the status of the observer, its prominence as a literary trope declined in the nineteenth century. As rational scientific knowledge replaced the use of metaphorical example, so the camera obscura’s ability to represent the eye and to act as a metaphorical link between external world and inner thought, was superseded by the emerging language of psychological discovery, reframing discussion about the interaction of outer perception and inner mind.

The use of both city and interior as metaphors for the workings of the mind, was anticipated to some extent by the interior condition inherent to the camera obscura. The Surrealists presented an interpretation of modernism that explored the irrational alongside the rational, often using photography to explore links between city and mind. As previously noted, Atget’s photographs of thresholds and doorways were cited by Benjamin for their portrayal of a surreal sensibility in exploring boundaries between interior and exterior that coincided with the development of psychoanalysis, noting that,

‘… no face is Surrealistic to the same degree as the true face of a city. No picture by de Chirico or Max Ernst can match the sharp elevations of the city’s inner strongholds…’ [8]

As the photograph superseded the camera obscura, it seems that its connective spatial model changed. Beatriz Colomina suggests that the interiority on which that apparatus depends had become subsumed into the image itself as the negative within the camera became indistinguishable from the printed, externalised picture.[9]

Not only does the camera obscura connect visually between the interior and exterior, but it also opens up an analogy between the outer world and inner thought, processes in which the strange and irrational come to the surface. The blurring of boundaries between reality and imagination that the interior view provides, can create a disturbing experience in the processing of inner thoughts and memories. The eerie sense of silent movement projected onto the camera obscura’s surface, heightened by the “cosy”, quasi-homely atmosphere of the darkened chamber, instils a quality, consistent with encounters with the everyday in which the familiar takes on a strange sense of its opposite, the uncanny[10].

Following the Surrealist notion that the city can be changed by the way we look at it, I return to the two water towers for their capacity to show the interior as a bridge between outside and inside. In the rooftop perspective afforded by Whiteread’s water tower, the cast of the tank’s inner space is turned inside out. Set alongside the outward faces of its neighbouring cisterns, this interior gestures towards now obscured memories.

Similarly, the camera obscura at Tavira shows how the inside of the city has become obscured in urban discourse by the visual apparatus that purportedly displaced it. Is it that photography, rather than simply evolving from the camera obscura, created a different sense of space in which the interior becomes subsumed into the photographic image; where the interior, disappears in its own representation?[11]

Reflecting in the Dark

As the mirror is once again obscured, the room darkens and I am left to reflect on the camera obscura’s ability to reveal the city to the observer who engages spatially with a reflection of the world. The interior condition, in both its physical and metaphorical forms, has the capacity to mediate between the inner mind and the outer world.

Investigation of, and through, the interior can move us towards an imaginary and atmospheric city triggered by inner memories. In pursuing the goal of new interior knowledge, conception of the interior for its doubled state opens possibilities for the negative to reveal something that the scopic realm has kept hidden. A photograph can convey an atmosphere and trigger an emotional response just as the cast impression of an interior is able to convey the memory of its past. By distancing subject from object, the photograph and the cast reconnect with inner worlds that are both strange and familiar, yet hidden.