Making Together: Three Little Tea Rooms, Details and Spaces, Re-constructing Garden

Abstract

The following article describes and reflects on three 1:1 construction projects, undertaken between 2014-17, each with a cohort of first-year BA (Hons) Interior and Spatial Design students at Chelsea College of Arts (University of the Arts London). Three Little Tea Rooms, Details and Spaces and Re-constructing Garden are part of an ongoing collaboration between the course’s staff and students, architect Takeshi Hayatsu, the College’s workshop technicians, the local community of Millbank (the College’s neighbourhood) and others. All three projects explore the transition between drawing and building; the importance of scale and how diverse materials and different methods of construction influence the quality of the spaces they produce. The briefs offered students, at a very early stage of their professional careers, an opportunity to be involved in ‘live’ construction projects, with tight budgets and timescales, working alongside architects and other professionals. Importantly, all three projects introduced first-year students to collaborative practice. Drawing on student and staff feedback, this paper considers what impact the projects had on the cohort’s social dynamic, on their studio culture and on their growing understanding of the importance of skills for working with a variety of people from a wide range of backgrounds.

Making in Public

Re-constructing Garden, Details and Spaces and Three Little Tea Rooms all took place on The Rootstein Hopkins Parade Ground, a 3500 sqm. courtyard at the heart of Chelsea College of Arts. Prior to the College moving to the site in 2005, the buildings housed the Royal Army Medical Corps and the Parade Ground retains its name from this former use. The courtyard serves as a large outdoor gallery for the College, exhibiting the work of staff, students and others throughout the year. Most notably, it serves as the focus of the BA degree shows in June and the MA degree shows in September [1]. The Parade Ground is fronted on three sides by buildings that comprise the College and traversed daily by those moving between the campus’ offices, studios, workshops and other provisions. The Parade Ground is also a thoroughfare for tourists, with Tate Britain sitting on its fourth frontage, and workers in nearby office buildings, providing a shortcut to and from local attractions, places of work and transport facilities.

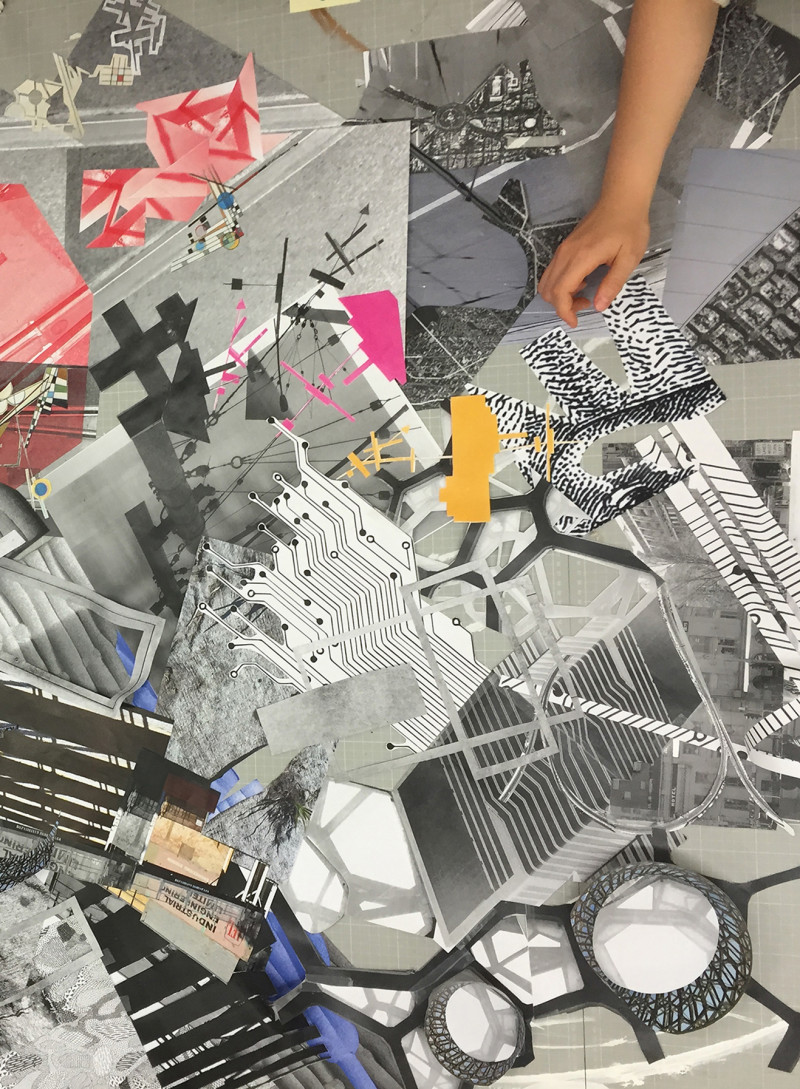

Since 2009, the Parade Ground has been the site of a series of projects by the Chelsea-based Critical Practice Research Cluster. Their projects explore the contested topic of being in public through the idea of ‘assembling in public’ - ‘[Their methods of working] aim to embrace the disagreeable, contentious, messy, inefficient, live, improvisatory and provisional nature of Being in Public [2]. Re-constructing Garden, Details and Spaces and Three Little Tea Rooms, share this practice-based ethos, which is proving invaluable to bridging the College’s graduate and post-graduate programmes. For the duration of each project the Parade Ground became our studio, with the mistakes, problems and messiness involved in full-scale construction by a large group of inexperienced first-year students put on display [Figure 1]. The extended College community and the public were ‘invited’ to join, passers-by stopped to ask questions and offer suggestions and became legitimate peripheral participants in the live project’s ‘community of practice’ [3]. Passing staff and students joined in the construction process – ‘because it is fun’ – and stopped daily to view and discuss progress. The projects became a point of conversation between students and others from across the College, fostering informal exchanges regarding construction, materials, sustainability, collaboration, making in public and engagement.

Making it Local

That the projects should take place locally has been a guiding principle. Re-constructing Garden, Details and Spaces and Three Little Tea Rooms exemplify my commitment to collaborate with neighbourhood stakeholders and co-produce a local, creative and resilient ecosystem in the environs of the College. With Chelsea serving as a community anchor, these projects became a space to critically explore and exhibit what the community has to offer the College and vice versa. This undertaking is situated within a renewed and growing interest by higher education institutions in the Civic University [4] and the collaborative turn taken in higher education [5]. All three briefs were live projects developed in collaboration with local stakeholders and partners. Live projects are understood here as emphasizing the invaluable role that learning plays as it connects academia and the students involved to the worlds beyond, with an emphasis on the collaborative and participatory skills essential to future practice [6].

All three projects involved between 75 and 90 first year students and were designed to mimic professional projects, with students divided into teams focused on design, management, logistics, structure, health and safety and documentation. Alongside the local community collaborators described above, students also had the opportunity to work with a series of professionals to develop the designs. All three projects were conceived and taught in collaboration with Takeshi Hayatsu Architects, which brought emerging architects on board to offer additional support during the construction process. Students and staff also worked closely on all the projects with the College’s workshop technicians, external projects’ team and the estates team.

Both the Royal Horticultural Society and its flagship event, the Chelsea Flower Show, are within walking distance of Chelsea College of Arts. The first of the three projects, Re-constructing Garden (spring - summer 2014) featured as part of the Chelsea Fringe [7]. This grassroots garden festival was set up to provide an affordable alternative to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show. Re-constructing Garden was a reconstruction of the Urasenke Konnich-an (今日) tea garden (Kyoto, Japan) [8]. The garden complex comprises a series of small structures, including a tea house, a minimal space of two tatami mats (approx. 4 sqm.). Traditional tea houses in Japan are designed to visually merge with their local environments and are commonly constructed from natural, locally sourced materials. As a project that aimed to critique the Chelsea Flower Show, the choice of construction materials was important. The starting point for the construction was around 100 discarded Christmas trees collected in the local neighbourhood of Chelsea after the 2013 festive season. Our reconstructed garden was situated on the grass square that forms the centre and focal point of the Parade Ground. We ‘transformed’ the original garden design with the ‘Mitate’ concept, a kanji compound composed of the character 見, meaning ‘to see’ or ‘to show’, and the character 立, meaning ‘to stand’, literally ‘a new point of view’. Often used to describe something that surprises a viewer, sometimes a visual metaphor or allusion, or something that is not exactly what it seems. The garden complex was represented using a 1:1 measured ‘drawing’ with a series of 1:1 Christmas tree constructions extruded as three-dimensional structures. With students divided into groups, each started by making 1:10 models of their part of the garden, these were then translated into scale drawings. Prototype details were developed through a series of workshops, using what was to hand because that was all we had. The trees were cut, chiseled and extended to form structural columns for the bench, toilet, gate and teahouse [figure 2]. In keeping with the importance of views and viewpoints in traditional Japanese gardens, the final orientation of the structures was carefully chosen in consideration of the sight lines enabled by The Rootstein Hopkins Parade Ground [Figure 3].

Details and Spaces (spring - summer 2015) was a collaboration with the College’s next-door neighbour, Tate Britain. As a continuation of the collaborative spirit established during the previous brief, this second project aimed to strengthen relationships between the two institutions. Tate Britain was built in 1897, with numerous extensions added over the years. Throughout this growth, it has retained its neoclassical language of architecture, including in the recent remodeling by Caruso St John Architects. The buildings that now house Chelsea College were constructed during the same period as the Tate, on the former grounds of the Millbank Penitentiary, in the style of Imperial Baroque and French Renaissance. Both sites are a treasure of subtle and beautiful details and ornaments. Students studied and surveyed these architectural details, documenting them in drawings and models, as well as imagining spaces hidden within [Figure 4].

Three Little Tea Rooms (spring - summer 2017), the third project in the series, was conceived in collaboration with the Japan Foundation. Their support enabled Japanese Architect Shinichiro Hashiguchi to stay in the College’s artist-in-residence flat, to work with the students and to bring from Japan his award-winning String Tea Room that provided the inspiration for the project. Hashiguchi’s research explores contemporary uses for traditional Japanese martials and crafts, with the String Tea Room a steel frame cube structure, measuring 2 x 2 x 2m and wrapped with the traditional silk of the Kyoto region. In Three Little Tea Rooms we reconstructed the Myokian Kyoto temple Tai-An Tea Room. Designed by the sixteenth-century century tea room master Sen No Rikyu, it is a minimal space of two tatami mats, also with an internal spatial volume of approximately 8 cubic metres. The tea room is constructed from indigenous materials, such as thin timber frame, bamboo lattice and mud wall lining. The proportion and scale of the original tea room were examined by the students, using cardboard 1:1 prototypes, detailed 1:10 scale models and technical drawings. These were translated into three different materials, straw bales, plywood and brick, referencing the old English folk tale The Three Little Pigs. We wanted to test how different materials and different construction methods would influence the spatial quality of the original. Students discovered the impact of standardized material sizes on the size of the openings and the scale of the rooms; and the impact this in turn had on the quality of light and the original arrangement of openings, which had been carefully designed in relation to function and views [Figure 8].

Three Little Tea Rooms featured in the local guide of London Crafts Week in April 2017 [Figure 9]. My long-term local collaborators, Millbank Creative Works, helped with the construction of the tea houses and after the installation all the materials were recycled locally: the bricks were used for a local community garden run by Millbank Creative Works, the straw was donated to the local city farm and the wood found a use as part of the BA fine art degree show.

Making Together

It is notable that the students’ self-evaluation forms revealed that without exception, they found the project a transformative learning experience. The students described learning how to develop a project from drawing to reality. They also reflected on the large number of factors that need to be considered [10]. They talked about the importance of 1:1 testing in order to understand how materials and structures behave, the importance of accuracy [11] and the contribution experimentation made to achieving successful results. They noted their improved making skills and confidence to work with tools. The students also commented on their positive engagements with the public [12], on gaining confidence in communicating their ideas to a variety of audiences [13]. And they talked about feeling privileged and proud to work on a live project at such an early stage in their careers [14].

Something surprising across all three projects was how the students’ attitude to working collaboratively shifted during the process. Initially reticent to work with others, by the end of the builds they recognized this as a vital source and site of learning [15][16]. They acknowledged the difficulty of working and communicating within a large group and, as such, the sense of achievement when an agreement was reached [17]. They described learning to compromise, learning to give constructive feedback and the opportunity to gain knowledge from peers and share ideas [18]. They further mentioned realizing that problem solving was quicker in a group [19]. Many students discussed the importance of time management and planning, to meet client deadlines but equally importantly ‘because team members depended on me’. Importantly students also described the projects as fun, talked of having a great time and acknowledged the opportunity to become closer to their classmates. Students frequently described the final results of this team effort as ‘amazing’, ‘impressive’ and ‘unexpected’.

Perhaps even more surprising and encouraging were the projects’ impact on of the students’ three years at Chelsea and beyond. As part of the 2017 graduation show, students were asked to produce a postcard with an image of their final project on one side and a reflection on the most memorable moment of their undergraduate journey on the other. For a significant number of students this was their experience of ‘making together’ in their first year [20]. They highlighted the sense of pride constructing a full-scale structure and the confidence this gave them moving forward; describing gaining the tools to work well with others and an understanding of how important these are to their career [21][22]. They also noted the lasting personal and professional friendships they formed [23].

As students’ progress onto the second and third year of the BA (hons) Interior and Spatial Design, they engage only minimally in collaborative work, focusing instead on developing their final thesis project. As an educator and practitioner, my teaching philosophy stems from a belief that addressing the complex issues we are facing as a society is more effective when done collaboratively. This includes experts but also, and importantly, lay people: community members, groups and others. With this in mind, it is encouraging that the students’ main takeaway from their three years at Chelsea was the experience of working together.