Designing interiors through making

ShareIn context with an age of social media, preoccupied with the omnipotent digital image, this paper highlights the importance of sustaining haptic investigation in the pedagogic process of designing interiors. By engaging with tangible form, through the act of making, both designer and client move closer to understanding or imagining a ‘real’ sense of place.

“At the beginning the material stands alone” [1]

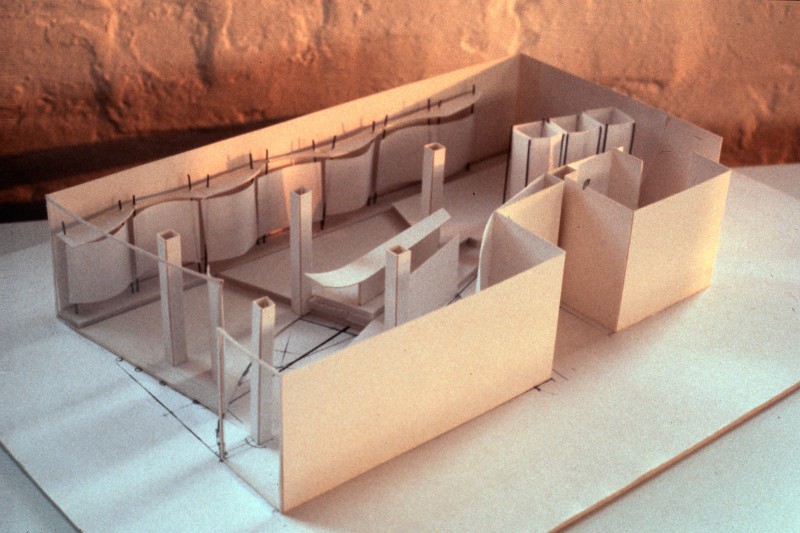

When I formed my design partnership we were required to compete against other designers for a very important project that we hoped would help to establish our practice. For the presentation I made a very simple 1:50 model of the space - a new store for Japanese fashion designer, Michiko Koshino [Figure 1]. Despite the effort that was applied to the pitch and graphic presentation, which comprised of the usual concept sketches, orthographic and perspective drawings, during the presentation, the white card and paper model was the major focus of client attention. Michiko smiled approvingly when she first saw it and couldn’t resist referring to it throughout the meeting. We secured the contract to design the store, but I feel sure that we would have been successful had we only presented the model. Such was the impact of that tangible form.

Why was this the case and why is it that physical models remain so seductive? What is it about a well-designed and made model that is so engaging? Is its resonance even greater today because, in this digitally dominated age of communication, encountering an actual three-dimensional manifestation of a design idea comes as a relief from the excessive demands of flat screen interaction? Or is it simply the immediate presence of the idea in three dimensions that is so appealing? Architect, Emily Abruzzo considers the physical model to be “the material embodiment of an idea, and therein lies its magic. By becoming real, it gives life and actuality to an idea in a way that two-dimensional expressions rarely can”[2].

Encouraged by the success of our first project we continued to make models for clients, not because we were sure they would be impressed with them but because the physical manipulation of forms in space, that quickly turned our ideas into three dimensions, aided our design process and helped us to make critical decisions that perhaps would not have been so obvious through sketching or other modes of drawing. There was also an attractive element of freedom that could be explored in the process of model making. But this was in the days before the digital realm had established itself as the primary means of distilling and disseminating detailed design proposals. Like most practices we embraced the advantages that computer aided design (CAD) brings, not least in terms of time efficiency, and therefore our preoccupation with the physical model eventually waned.

It is now, of course, all too easy to design and model an interior space in a variety of computer programmes. Although this technology can produce explicit representations, there are however limitations in relying on this resource alone to develop ideas within a learning environment. Through the digital medium it is difficult to understand scale. It is difficult to appreciate and learn about materiality and it is difficult to convey a multi-sensory experience of space. In my approach to teaching, therefore, I have consistently endorsed physical model making as an antidote to the addictive allure of the digital screen, advocating it as a fundamental pedagogic tool in the design process. Although designing through model making is less evident in practice today, due to obvious time constraints, I strongly believe that its benefits to the learning experience should continue to be acknowledged. It should be considered an important cognitive skill, to be deployed alongside physical sketching and digital visualisation with equal merit.

The physical model bares inherent evidence of the maker’s individuality that offers an alternative to the prolific production of generically conceived digital models. Haptic interaction in the model making process evokes an experience of material, not only in the tactile sense but also relative to size, scale, weight, transparency and sometimes smell. In experiencing these qualities and characteristics when physically handling material, questions are provoked about their choice and effect on the potential design outcome under consideration that may not be raised through digital investigation. As Bob Sheil points out “making is a discipline that can instigate rather than solve ideas”[3].

In his seminal book, The Eyes of the Skin, Juhani Pallasmaa refers to the effect of peripheral vision upon our existential perception of space. “Focused vision confronts us with the world whereas peripheral vision envelops us in (to use Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s evocative expression[4]) the flesh of the world”. Pallasmaa expresses concern here about the impact of digital interaction and the architectural fraternity’s continued obsession with on screen vision, its perspectival representation and the distance it creates between the maker and the object. [5]

On our undergraduate programmes we stress the relevance of designing through making in a number of ways. This starts at the very beginning of the study, by encouraging students to think about the tangible articulation of form and space through simply folding and cutting paper to create three dimensional forms. As students become familiar with the development necessary to arrive at any design conclusion they learn to appreciate how model making can aid the design process and sharpen their creative awareness.

Students of interior architecture and design are typically limited to representing design outcomes merely in graphic or model scale form and although conceivers of the ideas, they are generally not exposed to the thrilling experience of being on site and witnessing their ideas come to life. This is an important part of the interior designer’s role in professional practice that concludes in experiencing the inhabitation and public use of the environments designed. However, in practice, most architects and designers do not make buildings, they make information for buildings[6]. Nor do all adhere to Andrea Deplazes’ ethos that “for me designing and construction is the same thing”[7]. In fact, in recent years, a proliferation of independent project managers, design and build companies and professional services, that enable sub-contracting of production drawings, has served to distance creative design from the construction process and often compromised quality. However, as a counterpoint, the emergence and sophisticated development of CAD/CAM (Computer Aided Manufacturing) interfaces is bringing back control to designers, allowing them to design directly for manufacture.

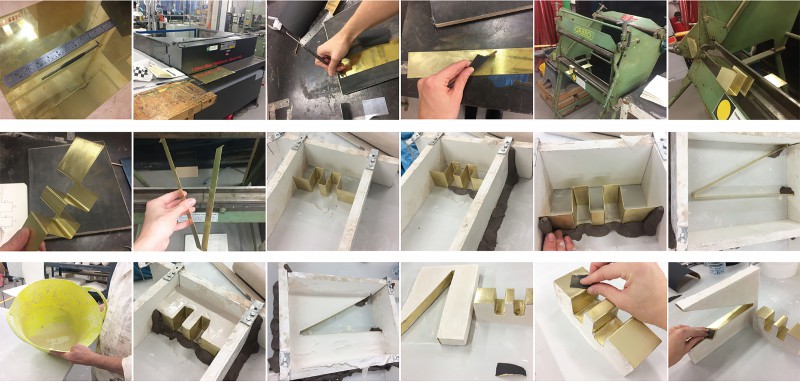

To reflect developments in industry, we also encourage our students to exploit and explore our excellent on-campus resources that integrate digital design programmes with CAM facilities such as laser cutting and 3D printing. Although, we warn of the misconceptions that can emanate from the homologous production of spatial form in a single material. We therefore tend to direct the use of these making tools towards the realisation of component parts rather than the whole.

In further consideration of professional practice, where possible, we make opportunities available within the course curriculum for students to design in groups and construct small interior environments at full size [Figure 6]. These projects help students to gain a greater understanding of structure, materiality, the effect of light and construction detail. Student experience is unquestionably improved through physical, material investigation and experimentation, aided also by working collaboratively in a team, as is more likely in practice [Figure 7]. During this activity of making, haptic and other sensory responses are engaged that are not evident when designing solely on a computer. The energy, enthusiasm, sense of enquiry and ultimately fun generated during these projects enhances student satisfaction and learning year on year.

Through understanding making we come closer to imagining potential human interaction with material, form and space that ultimately defines atmosphere and multi-sensory experience. The ambition of students immersed in the design of interiors through making should be to understand how places are made and how their respective component parts are brought together to create an appropriate experience for the occupier or visitor. Learning through making then is still vitally important, possibly now more than ever before. It is fundamental to the pedagogic process and an essential aid to gaining a clearer appreciation of the essence of place.

It is hoped that by embedding this approach to designing interiors within the learning cycle, the experience will be positively instilled in graduates who progress to influence the profession. Thus we will see growing evidence of richer, multi-modal environments in creative practice, that operate through a kind of circularity between sketching, digital drawing and physical making and back again[8]. I am convinced, through both my practice and teaching experience, that this form of praxis results in far more sensitively built environments.