Making a Scene

Abstract

This paper describes making strategies for independent, intercultural and industry making in an undergraduate interiors programme. A belief that making is central to the development of spatial, material and contextual understanding underpins this paper. The following case-studies include emotive making at the sculptural object-scale; intercultural making at the installation / place-scale and collaborative industry funded making using mise en scène principles which explore dwelling concepts.

Background

Making puts pressure on resources but far from reducing this we need to extend our making practices. However, we are also dealing with a new generation of students which Sharp describes as ‘mosaic thinkers’. These are individuals who make meaning out of fragments, whose learning is non-linear and who are increasingly digitally dependent[1]. However, it is in making, in particular, where students could develop distinctive work, confidence and enrich their spatial understanding. Making is also a research method in the authors relatively recent funded research in user engagement and in larger ‘allegorical’ constructions used to convey research findings normally expressed in text[2].

Making Un-Making Re-Making

Making in interiors is somewhat paradoxical and contradictory. We are preoccupied with ‘built’ experiences but do not ‘build’ per se, rather we fabricate i.e., we invent in order to deceive, or skillfully construct from prepared components. Riley describes fabrication as an equally slippery tectonic term that shifts continuously depending on its context, and which, “…jumps between the negative sense of a falsehood and the more neutral sense of the process, or product, of making.”[3] Whilst its etymological opposite implies the negative razing or destruction of something, a more positive example is our Deconstruct /Reconstruct year 1 project which reverse engineered found-objects from local waste-streams. This raised awareness of sustainability but also introduced students to adaptive re-use principles, indirectly, through the remaking of found / dysfunctional objects into new uses [4] This razing and resurrection suggests a conceptual link to Machado’s scraping or over-writing palimpsest [5]; Matta-Clark’s controlled demolitions [6], and Richard Meier’s reanimated sculptures. Meier’s intuitive making is distinct from his architectural oeuvre and has inspired emotive making in our own programme. Often using found-objects and the detritus of his architectural models, Meier uses wax resist techniques to create dark, metallic objects that are the aesthetic antithesis of his buildings. In his acts of re-animation he leaves traces of the casting process in the finished works as a “kind of artistic cannibalism [and] as a way of breathing new life into the abandoned models: recycling as reanimation.”[7]. Collectively, these hint at a cyclical relationship between place-makers and maker / fabricating and fabricators’.

Whilst the scaled-model retains its prominent position across UK programmes, it is our fascination for miniaturization which is compelling and ingrained in our memories. Limbrick’s 1964 open-sided doll’s house expresses this fascination as a designed solution for collective play in nurseries where the form was previously exclusive and expensive [8]. Spankie and Araujo’s research into the dolls-house offers an interesting conceptual template for the new interiorities and as a “...a potential ‘modelling tool’ for interpreting and fabricating the domestic interior [to] engage the student or designer in a process of making that is comparable to the practice of interior design.” [9].

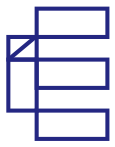

Emotive-Making at the Sculptural / Object-Scale

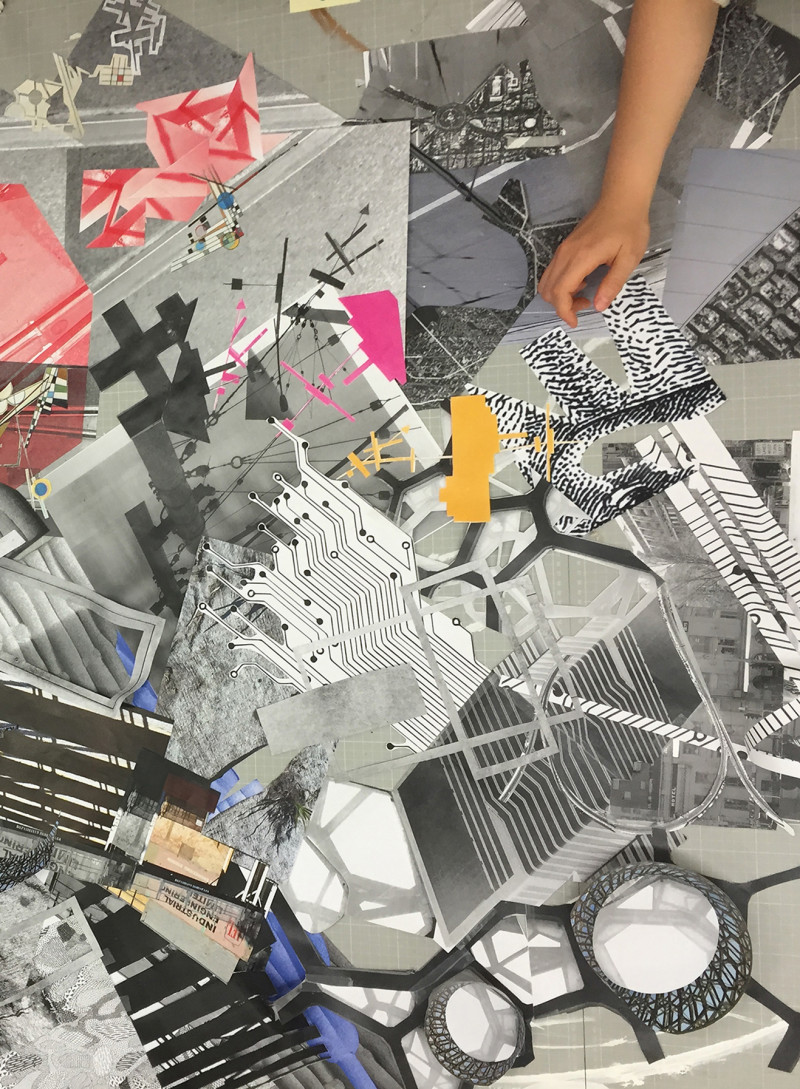

This project ran online for three-weeks over a three-year period. Designed to provide Year 3 students with a visceral and virtual making experience that simulated designer / client conversation, Scottish and US students were matched in teams of two and invited to enact roles as each other’s proxy designer and/or pseudo client [10] changing roles repeatedly as required. Whilst making was the outcome, the process was directed by the design of questions-from designer to client. The ‘clients’ responses provided the creative media which influenced the scale and form of the final emotive-objects. Simple questions such as ‘What is your favourite colour?’; ‘Do you identify yourself as Texan / American?; ‘How important is family to you?’ tended to allow for more relaxed responses though quality of questions and depth of responses inevitably varied. Rules-of-engagement were agreed ensuring effective communication in light of the six-hour time difference. Only written interactions were permitted with face-to-face exchanges prohibited rather than be distracted or led by the ‘appearance’ of their client. The teams only met face-to-face via virtual conference suites on the last ‘reveal’ day of the project. Individuals were finally able to ‘meet-their-(re)makers’ and gauge their client’s emotional reaction to their emotive objects [Figure 1].

The project explored how text and making coalesced in interesting and unexpected ways. Our aim was to expand students making expectations and capabilities, develop digital literacy, improve interpretive skills and consider alternative uses for language beyond those of site analysis or critical writing. The project exposed issues of intellectual and creative ownership; where it rested, the designer, client or both? Outcomes were particularly diverse often using improvised, traditional and digital techniques often sculptural in nature and including abstracted laser-cut cubes, pop-up books, narrative calling-cards (constructed, presented then mailed to the client recipient). Construction used analogue and digital making techniques. Student’s interpretation of the client responses initially took the form of diagrams and sketches as basic simple form generators. Responses were often visualized as timelines, or as symbolic and metaphorical references. Frequently, more nuanced interpretations sought to express conflicted cultural identities, e.g. as simultaneously Scottish and British; Texan before American, or Chinese to American identity [Figure 2].

Intercultural-Making at the Installation / Place-Scale

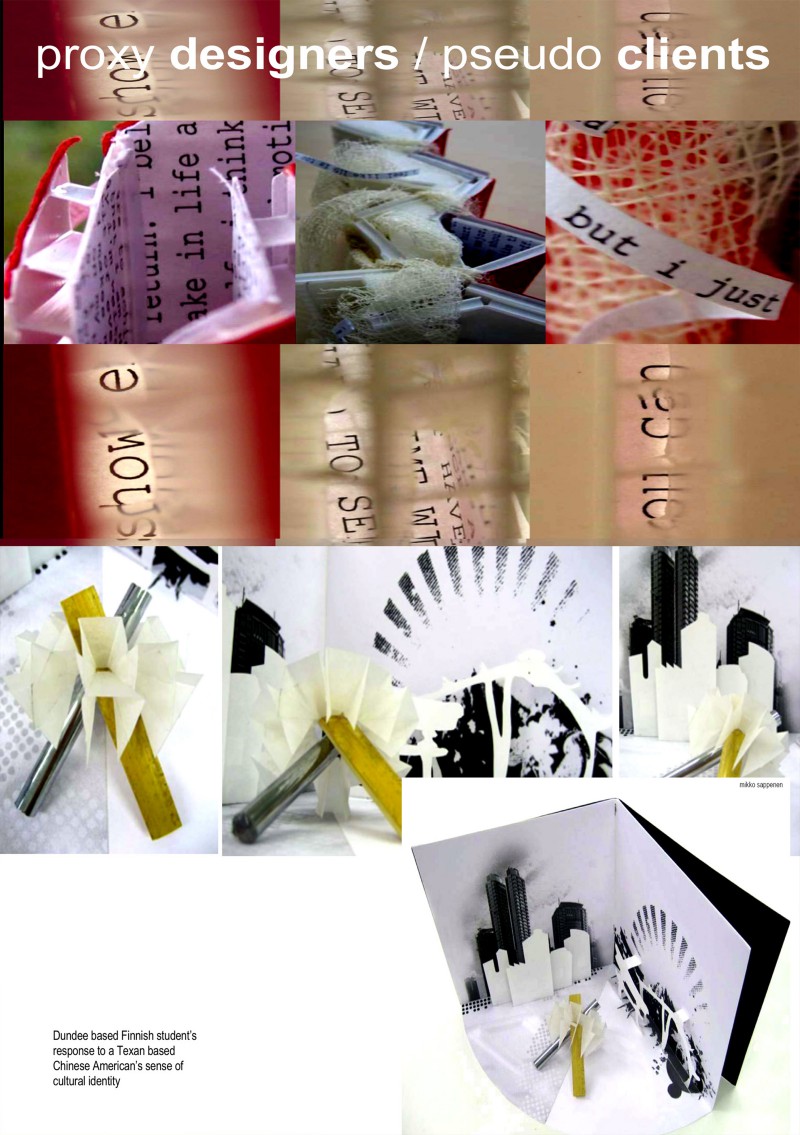

This Year 2 example was part of Border Crossings, a two-stage research-led module delivered between 2011-16 over an eight-week period in semester two which, at its height, involved partners from Finland, Canada, USA, Slovenia, Netherlands and Scotland [11]. The brief invited students from textiles, interiors or jewellery to explore identity through their specific disciplines, initially through a short research phase, and finally in collaboration with international peers on an on-line social network (e.g. NING). Supported by an EPSRC funded project, ‘IMPRINTS: Identity Management: Public Responses to Identity Technologies and Services’, this set the conceptual parameters of the brief [12]. In stage-one, collaboration was localised and research focused. Students developed research approaches over the first two-weeks. In week three, disciplines shared their research insights to unearth common-ground culminating in interdisciplinary outcomes that, surprisingly, took the form of installations. [Figure 3]. In stage two the international partners joined. Earlier research outcomes were uploaded to our NING network to encourage informal peer-to-peer conversations as international partners ‘met’ for the first time in one of three disciplinary streams with their disciplinary counterparts. This provided opportunities for informal benchmarking as a community of learners exploring a shared identity brief.

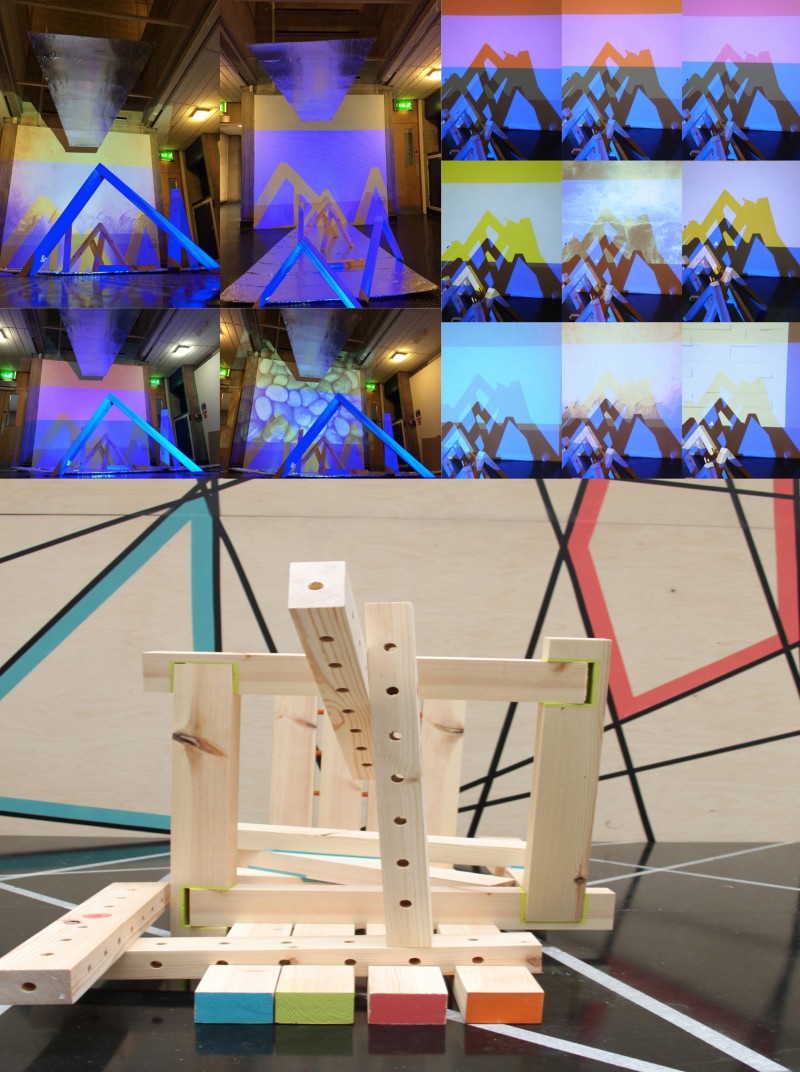

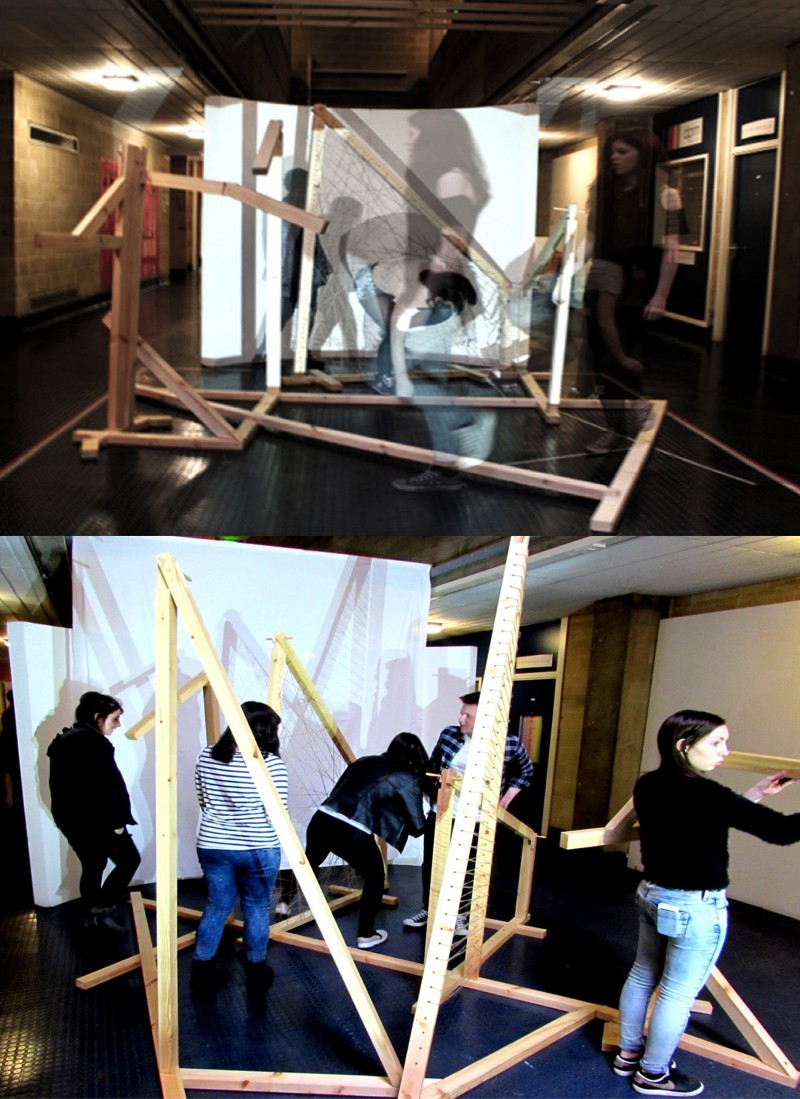

In 2015, a new making strategy was established involving Interiors in Scotland, Netherlands, Slovenia and USA. Using installation as the outcome, it was inspired by Humberto Schwab’s Socratic Dialogues methodology. This is a philosophical methodology that encourages individuals to challenge orthodox modes of [design] thinking and is predicated on dialogue, an openness to experimentation and deep-listening. This plays-out through a shared task - in this instance, expressing creative identity through an installation. As a process, it required small teams to take a leap of faith in adopting an organic line of enquiry and requires embracing risk (and risking-failure). As a methodology, it has some affinity to ‘slow-design’ principles and requires intrinsic motivations (experience led), rather than extrinsic motivation (grade driven) or indeed, risk-averse. However, this slow-flow of ideas required structure in the materials, assembly, dimensional and time constraints we set. Nails, screws or glue were prohibited but required improvisation of tight-fitting joints. The creative process required one school to take the lead in randomly selecting elements from the predetermined Hedjuk inspired ‘kit-of-parts’.

Gradually, an arrangement took shape following numerous assemblies over one day. Once completed, the precise construction sequences were transcribed (with images/ diagrams) and communicated to all partners on-line. Those partner teams would then collectively, and concurrently, follow the instructions and attempt to replicate the arrangement exactly over a 2/3-day time-frame. This sequence would repeat with one partner taking the lead, with consecutive iterations (and subsequent partners) seeking to build empathetically upon the previous construction phase of others. At the conclusion, approximately twelve iterations had been completed across four installations. Despite the constraints there was some variability of form with intriguing structure. [Figure 4] The learning experience was dynamic and encouraged students to improvise (with materials, their assembly and also their ‘bodies’). It also developed confidence in workshops, in online collaboration and on-site negotiation. Socratic Dialogues provides an intriguing philosophical route into making distinct from our current practices. As a highly iterative process, it lends itself to more instinctual and thoughtful construction that develops practical and holistic skills [Figure 5].

Industry Funded-Making at the scale Mise en Scène

Conclusions

Emotive-making exposed strengths and weaknesses. US students, though less conceptually focused, were excellent communicators. Scottish students were uncomfortable in verbalizing their making but excelled in conceptual design and were more ambitious in making. Each struggled to design thoughtful questions though their interpretive skills were encouraging. The Socratic Dialogues [15] installation study also used an on-line network. But students were resistant when they realised that their work, (like their social networked activity), would be similarly exposed. Installation outcomes were exciting nevertheless because of their unpredictability of the process. Both used conversation to inform making, whilst the industry funded HABLab energized students but allowed reasonable scope for teams to reinterpret the home/house themes whilst time and material constraints proved positive. Strategically, the micro-meso-macro themes were helpful in giving teams a creative route into the short project.

Notes

HABLab was coined by the author whilst a panel member of the British Council’s ‘What’s the Future of Domestic Life’ in discussion with Sumi Bose, Curator of Home Economics Venice Biennale.