Why Making Matters

ShareThe CASS as part of London Metropolitan University runs 3 Interiors courses, side by side, Interior Design, Interior Design and Decoration and Interior Architecture and Design. As level 4 organiser, and through studios at level 5 and 6, over the past 12 years, I have observed that once students understand how to draw for new technologies, such as laser cutting and 3D printing, they develop an over reliance on this kind of output, leading to less experimentation, critical reflection and above all a lack of materiality and haptic experience. This essay reveals my pedagogical approaches to develop creative conversations through making, by providing opportunities for students to develop themselves as learners through physical three dimensional responses and how tackling community and social issues through making, aims to demonstrates ‘why making matters’.

In recent years Interiors courses, have seen the relationship of qualitative critical, contextual research undertaken through testing, experimentation of materials, mixed media and technical making skills, eroded by the apparent ‘accuracy’ of new technologies. The Cass interiors courses teach vector digital skills such as Auto Cad from level 4. However, I have witnessed over a number of years that critical reflection and understanding through haptic development has been somewhat replaced by laser cut or rapid-prototyped models generated from digital drawings. The results are typically less developmental and lean towards a diminished material sensibility and an unresolved charred edged finality.

Higgs 2006 refers to “critical and creative conversations” to describe the process and practice of meaningful making. Therefore, implying, that in order to have a conversation and for that conversation to be transformative, the process needs to reveal an explorative, reflective and reflexive set of discussions.

This essay will demonstrate that a model or making, at a variety of scales, is not solely a representational tool, or haptic, tangible, analogous qualities of engagement with an idea, but an approach to encourage meaningful, ‘speculative and divergent’ discovery, with the potential to create greater paradigm shifts within personal and collective learning and above all to start ‘creative conversations’.

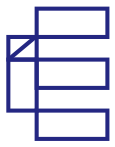

The translation of an interior concept is often represented by scaled models, models that express the spatial experience. [Figure 1] Technologies enable the design to work towards an accurate representation but not necessarily demonstrating the materials and the experience in the space. Testing the idea and its spatial possibilities through sketch models is part of our process and practice, however, the testing of the materiality may be limited to mood boards, visuals and sometimes handmade samples, to support the outcome with the model acting in a supporting role.

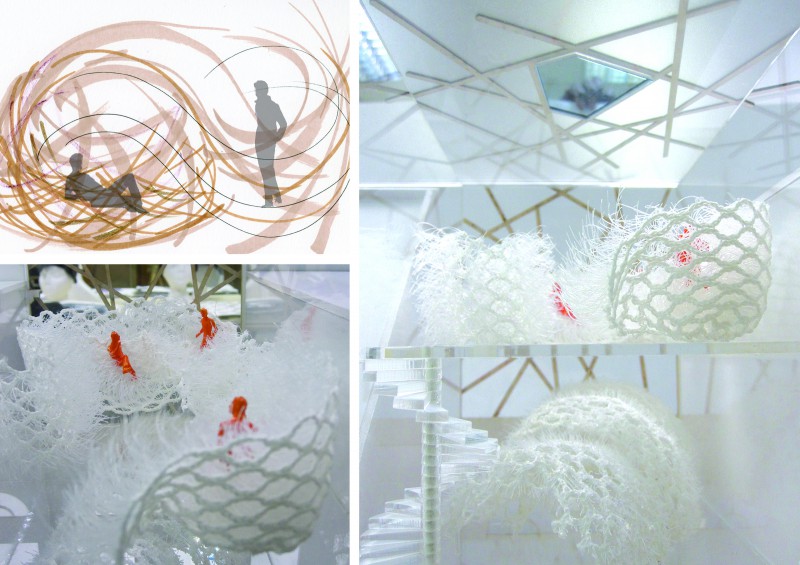

There is an argument that models attempting realism can be criticised as too representational, almost lacking control, unless carefully crafted. Subtle tones, no evidence of laser burns and adhesives, work towards a successful outcome [Figure 2]. Yet students may test and experiment creating real samples but lack the skills or time needed to effectively convey a realistic representation within a scaled outcome, hence simplified white or monochrome models are widely produced.

However, it is possible by using combinations of real materials, haptic skills and drawing to bring together an outcome that will be believable, with model material selection being a vital consideration. A neutral toned approach can be an excellent stratagem, encouraging the viewer, to project their own vision of the materials, colour and experience [Figure 3]. Indeed, within industry a monochrome model can be employed as a device to suggest a programme to their client, giving a starting point to negotiate or encourage a discussion. However, materiality creates the spatial experience, the texture, form, structure and kinetic quality of light and transition, there is value in exploring this through making.

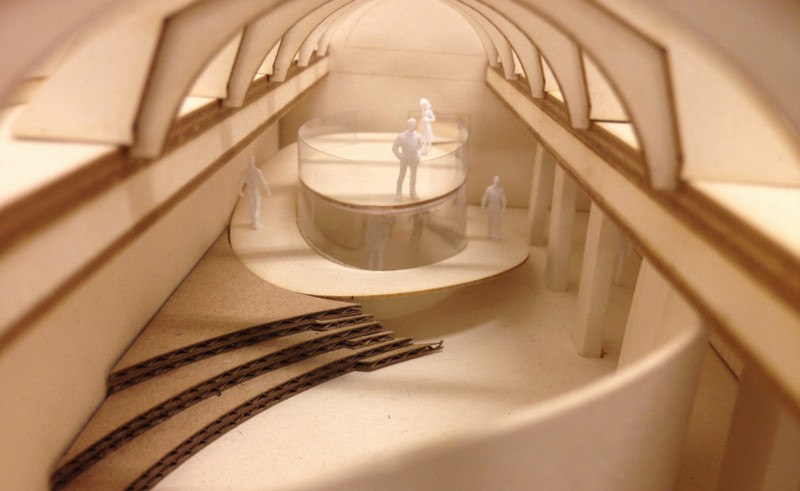

The Interiors cluster, within the studios I lead, have made a shift away from the reliance of technologies to enable the students to develop and engage with material experiential outputs, at scale and at 1:1. The studio at level 4, which includes a cluster of students from 3 interiors disciplines, has developed a programme of making that challenges students to consider materiality as part of the developmental stage of the initial concepts. The aim is to enable the cohort to create real experiences and interventions, often using haptic skills alone or combined with technologies. For example, in [Figure 4], the intervention into the space is handmade within an assembled laser cut structure.

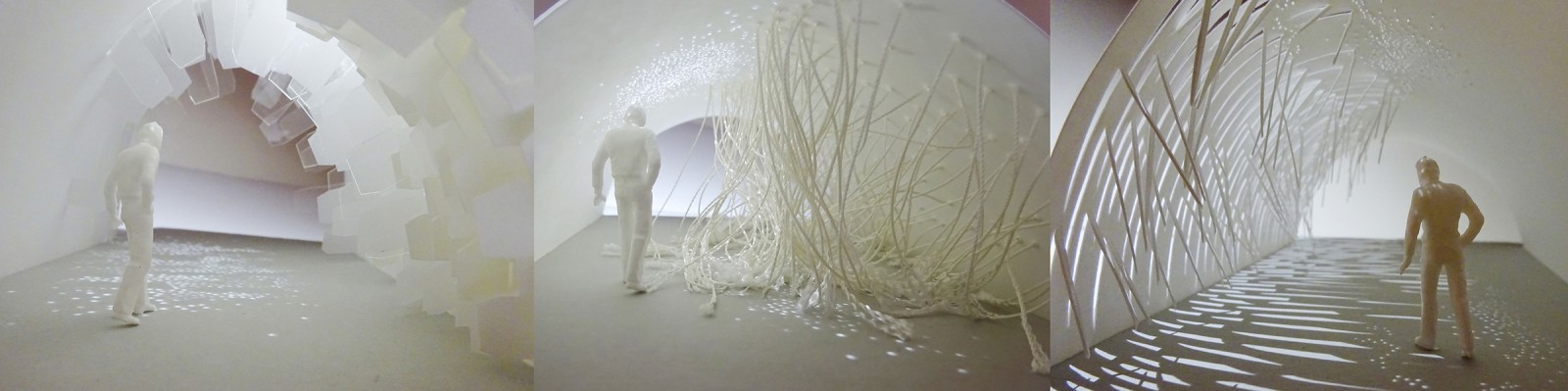

Level 4 starts with fast-paced model making, utilising hand tools only, translating personal narratives into a spatial experience [Figure 5]. In turn this approach develops critical analysis and reflection, using lighting and photography, leading to further development of ideas and speculation. The students are encouraged to share their techniques and help each other to see the potential and possibilities of each of their designs. The outcomes develop a collective consciousness of the reality of the designed element and spark debate about the possible interpretations of real or representational vs imagined experience.

Workshop inductions are combined with a project to maximise and enable meaningful learning. Time is allowed to test and improve skills and develop an understanding of materials, which informs material choices and specification. Manufacturing, construction and finishing techniques all adding to a critical conversation [Figure 6]. An immersive experience into the workshops and 1:1 projects help students understand process and practice, while developing detailing skills.

It is quite typical at level 4 for some students to strive towards the projects end goals as soon as possible, however making helps to develop a reflective approach that challenges the students to test and evidence their conceptual journey. Group work is encouraged for the 1:1 projects, which involves problem solving, communication and patience to create a successful output. Through careful guidance and studio workshop activities we can develop critical research approaches to support academic research. Students gain confidence and realise that they can enjoy ‘the process’ too.

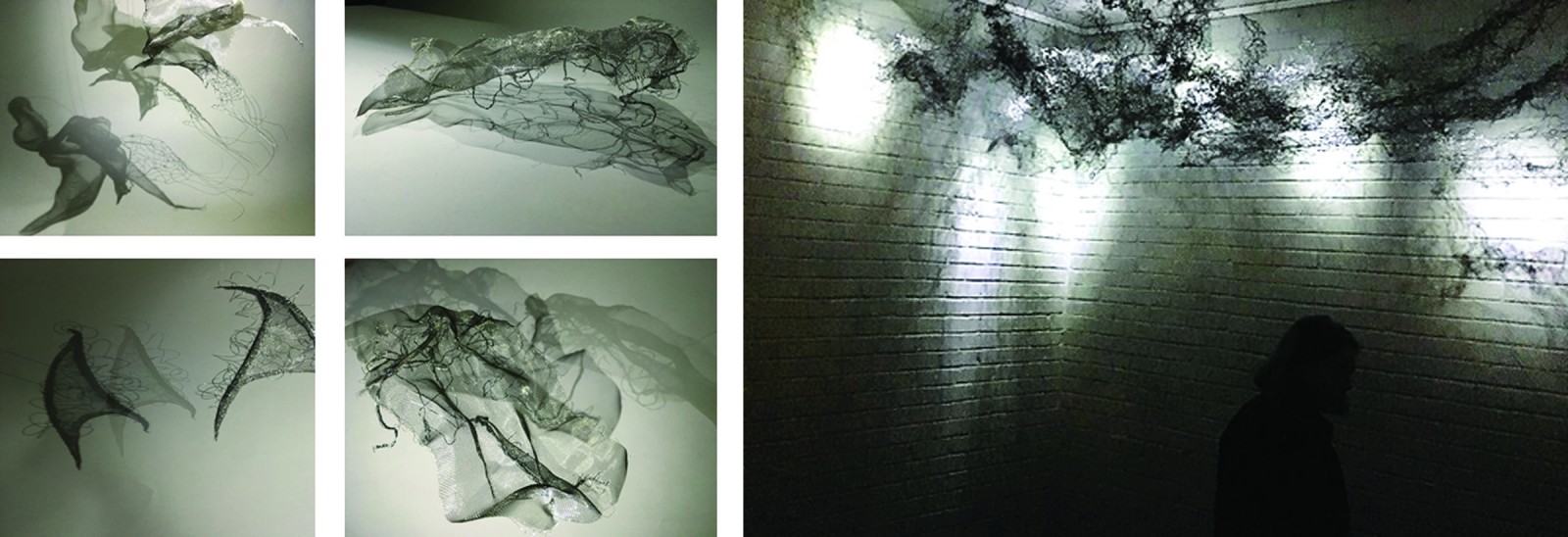

One such example is a 1:1 lighting project called Woven Narratives [Figure 7], based on Gaston Bachalard’s book Poetics of Space and his notion of corners and shadows encouraging dream space and therefore creativity.

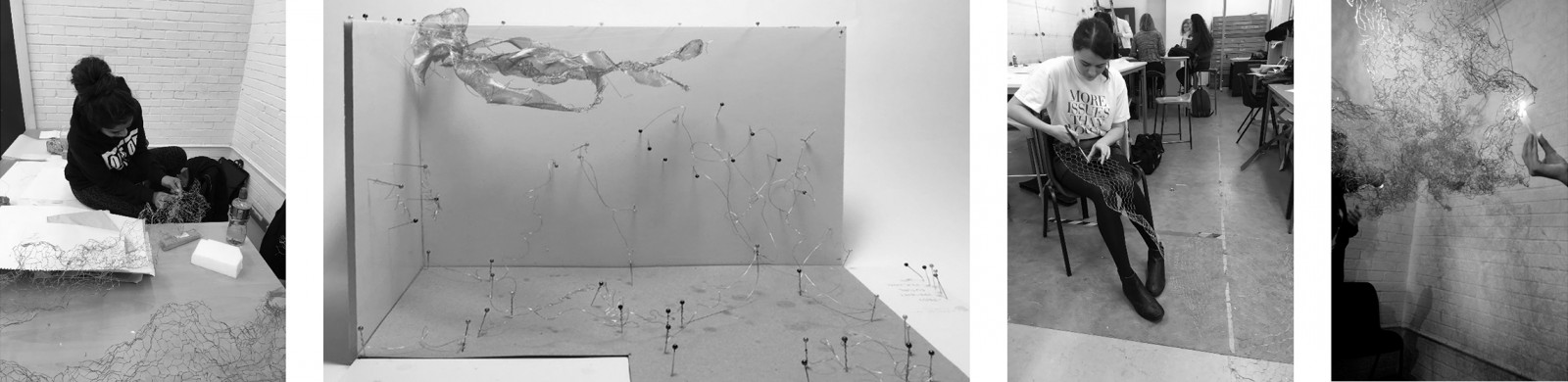

The students set themselves up in the corner of their studio and map, using a scaled model [Figure 8], their conversations while making. For instance, they talked about the making process, the challenges, attributes, themselves and their lives, this determined the various components and where they were fitted in the space. The outcome evidenced their process and practice and instilled a ‘creative conversation’ through materiality, light within a real setting but ultimately formed bonds between the students.

At all levels, it is important to develop meaningful learning opportunities, through live projects, where possible. We will often tackle difficult issues to develop a social conscience and try to create a paradigm shift that impacts and encourages lifelong learning.

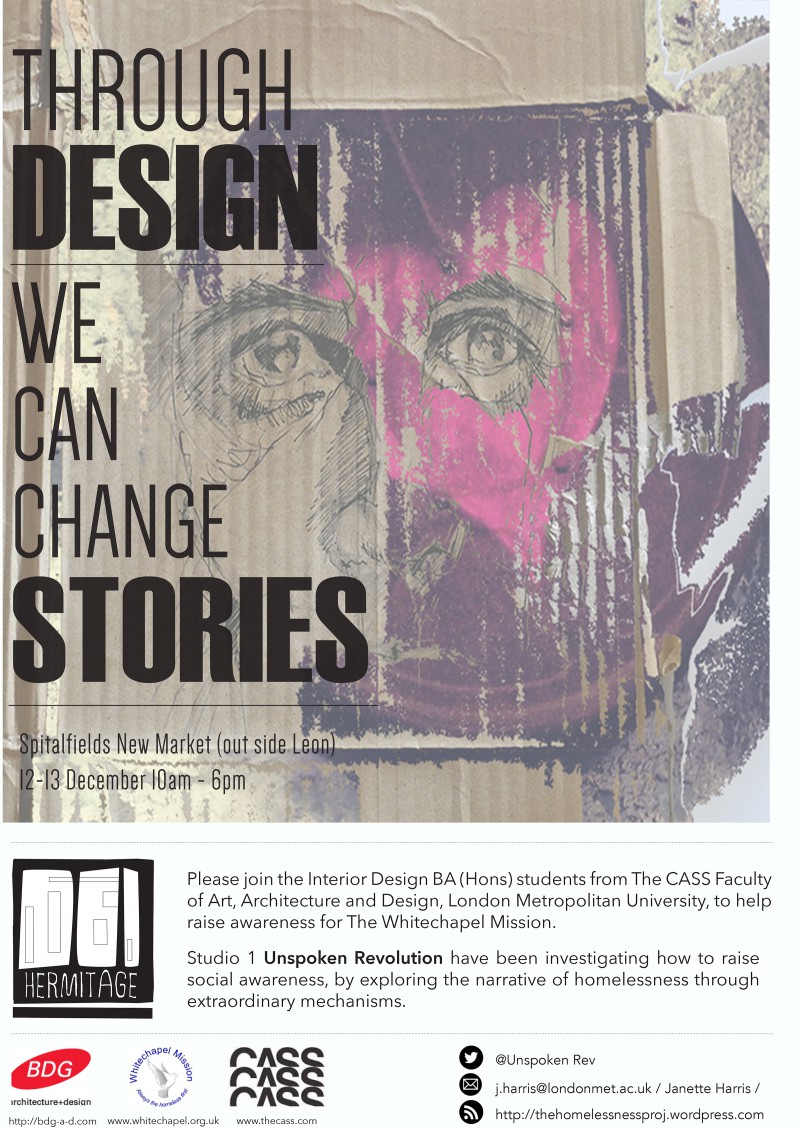

Projects such as the Hermitage in my studio ‘Unspoken Revolution’ (Level 5 and 6) highlighted the importance of understanding the issues of homelessness from the perspective of homeless people’s personal narratives, through Tony Miller and the White Chapel Mission [Figure 9]. The aim was to create and make a collective outcome with individual conceptual responses that challenged the general public’s perception through exhibition and presentations, while raising money for the cause. Students’ experience of developing and conveying difficult narratives through making became a point of responsible design. Enticing the general public into engaging with a curious structure and its materiality, to touch, read and interpret was vital to the success of the project.

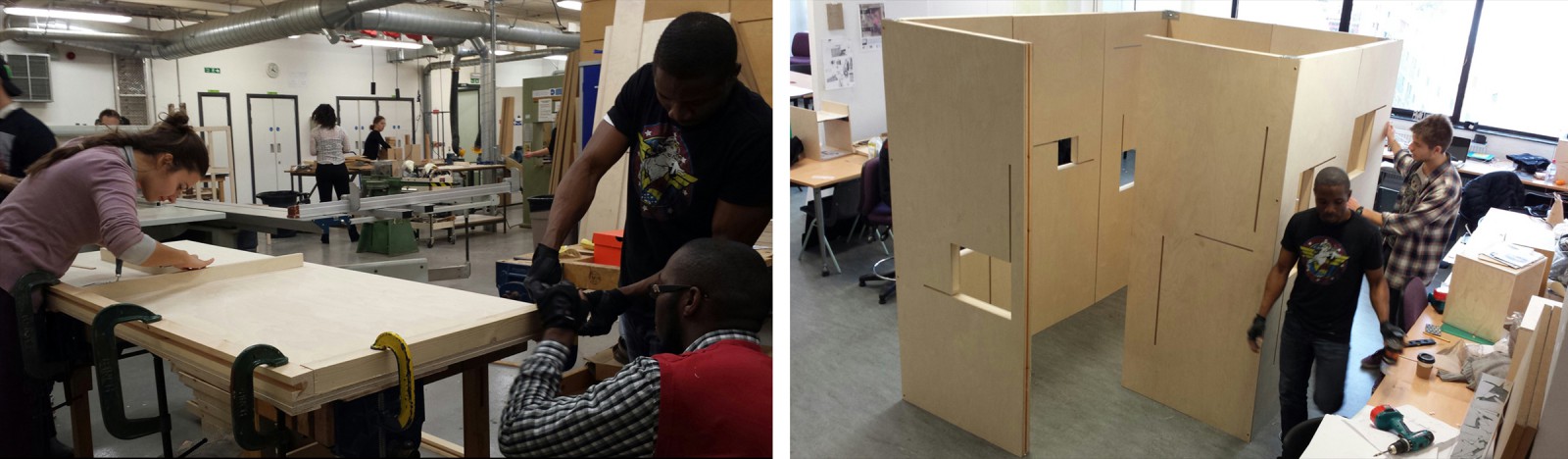

The students set up the project as if they were a design company, each volunteering for roles and responsibilities, with levels 5 and 6 working together. The aim was to not only build the project but to tour it. The students were encouraged to undertake heuristic strategies to design the space and personal stories through models and drawing, testing and debating their ideas with each other. BDG, who are trustees of The White Chapel Mission acted as our client, who critiqued and supported the students. A pitch had to be made to Spitalfields New Market and a proposal put forward to the residents of Spitalfields to request permission and a free space at in December to exhibit. At the same time promotion for the event through a blog and e-vites were set up. [Figure 10].

Meanwhile the students had to consider the materiality and manufacture of the intervention. How it came apart and reassembled, the delivery and its resilience for each venue and how these considerations played a part of the design strategy. The students only used CNC for parts of the structure, the rest of the outcomes where largely hand made using general workshop tools and machinery, such as circular saws, routers and band saws [Figure 11]. This was a conscious decision by the students, in respect of the reality of the issues of the project. The materiality of the narratives, all imbuing the same personal ethos and care [Figure12] utilising largely found or thrown away materials. The outcome not only developed a conscious connection between materiality and user experience, but the power of making, its ability to move people, to start a discussion and connect to a diverse audience.

Through making at 1:1 projects such as Woven Narratives and the Hermitage demonstrate that making can encourage ‘speculative and divergent’ ideas. Students undertake a complex journey where risks are taken, mistakes are made and testing fails but through these projects problems are solved and the process is discussed, debated and articulated to an audience beyond the confines of the university. Creating time for students to test, explore and learn while making is a vital part of their learning process. Students challenge and encourage each other to explore solutions and come to the realisation that ‘making matters’.