Productive design processes and creative collaboration: common grounds of fashion, music and interior design

Abstract

The paper presents workshops that have been applied in a BA2 studio in Interior Design in an exploration of the common grounds among fashion design, music and interior design. The workshop aim to generate discussions and design tools, that would support students into generating design briefs and alternative concepts, during their initial steps into the project. These workshop support the making process through the idea of analytical play, while introducing students to sustainability, co-design and different experimentations with materials.

‘Assemble’, the winners of the Turner Prize in 2015, describe themselves as “sort-of-architects” and “non-architects” and they work alongside set designers, carpenters and artists[1]. Droog, a similar but more established collective based in the Netherlands, present themselves as “a conceptual design company” that focuses on “matters that affect society and its people. The process is key. Our work is anti-disciplinary. And the outcome can be anything that contributes to society”[2]. ‘Participle', a London-based practice, also applied their design skills and participatory design methods to solving social issues such as encouraging a flourishing third-age, the engagement of disaffected young people and the reduction of re-offending rates[3] Emerging anti-disciplinary and interdisciplinary practices like these, point to a future where spatial design is no longer like a classical orchestra where each one plays their part led by a conductor, but has the spirit of jazz, a process of improvisation, call and response, with greater freedom for creative collaboration and co-designing.

With this dynamic professional context in mind, the BA2 Interior Architecture and Design programme at Portsmouth School of Architecture has been designed to encourage students to apply their creative skills to a broad range of problems and to understand and value the contributions of potential users, clients, other creative professionals; students are also encouraged to explore different routes into the creative process. This approach is underpinned by clear pedagogic principles that inform our practice:

- Learning sits within the framework of “process” and “praxis” where emphasis is given to experiential learning[4][5] and includes creative, iterative, and cognitive processes; knowledge and understanding is constructed by the individual

- To create a community of inquiry that encourages respectful and critical collaboration with others (tutors, students, practitioners, communities and clients).[6][7]

- To engender socially responsible attitudes and an understanding that design is an ethical act; to raise awareness of local, national and global issues.

- To encourage deep learning and to promote intrinsic motivation and critical thinking.

- To encourage the development of the student’s individual design identity informed by an understanding of practice, the broad cultural and social context of design and by reference to theory.

To support these pedagogic aims, the BA2 programme introduces ethical approaches to design and an engagement with theory and the wider cultural context of interior practice including art, craft and the broad spectrum of design practices.

Emerging anti-disciplinary and interdisciplinary practices like these point to a future where spatial design is no longer like a classical orchestra where each one plays their part led by a conductor, but has the spirit of jazz, a process of improvisation, call and response, with greater freedom for creative collaboration and co-designing.

To exemplify these pedagogic approaches, this article describes two projects, the first, Re-Make, examines the historic and contemporary connections between textiles, fashion and architectural design and associated environmental issues; the second project, Sound Space, introduces the students to participatory design processes and examines the creative connections between music and design.

Re-make: fashion-inspired approaches to sustainable spatial design

To stimulate the examination of historic and contemporary links between fashion and architecture, students were introduced to texts by Adolf Loos[8], Gottfried Semper and Bradley Quinn and referred to exhibitions like ‘Skin and Bones’ and ‘Lost in Lace’ . Based on this research the students mapped the common areas of practice including design processes, conceptual aims, use of materials and construction methods. To conclude this phase of the project the students defined a ‘lexicon for practice’ that could be shared by both disciplines and summarised their explorations.

To understand sustainable approaches to both disciplines the students analysed the objectives of the Sustainable Clothing Action Plan (SCAP) and considered how their aims for 2020 could inform interior practice. SCAP is a government-funded initiative to improve the sustainability of clothing across its lifecycle. It has four steering groups: the Design Group; the Re-Use and Recycling Group; the Metrics Group and the Influencing Consumer Behaviours Group. This last group has identified three key behavioural changes which consumers can make to reduce the footprints of their clothing, including: ‘Acquisition’ (consider purchasing pre-owned and reused clothing, the durability of garments and the source and quality of fibres), ‘In-use’ (caring for products, laundering & repair) and ‘Discard’ (the re-use & recycling of products). The students shared their findings and applied their understanding to the generation of designs that were socially, economically and environmentally sustainable.

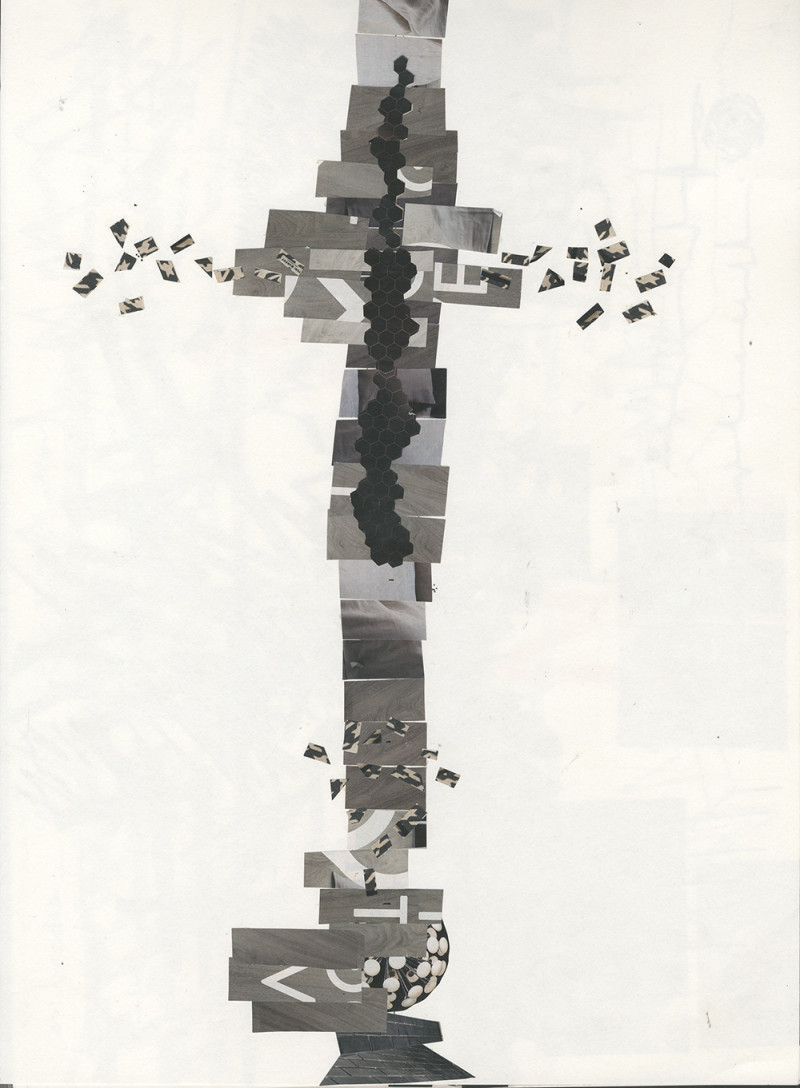

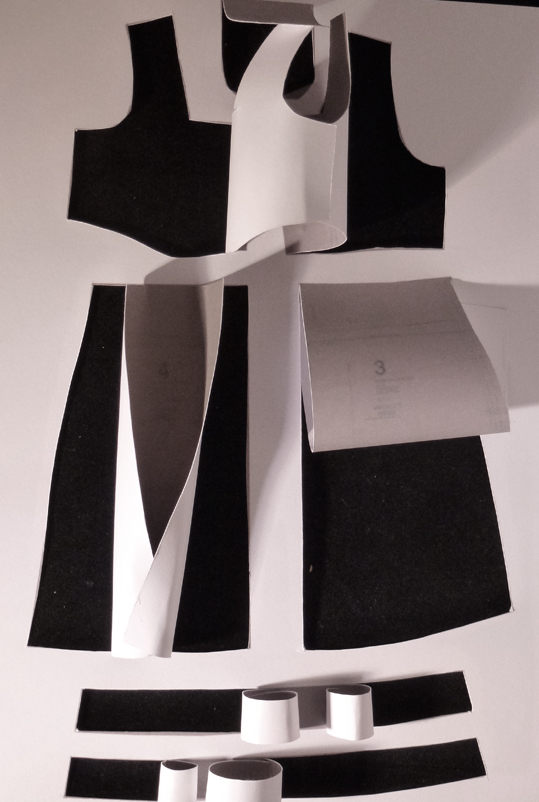

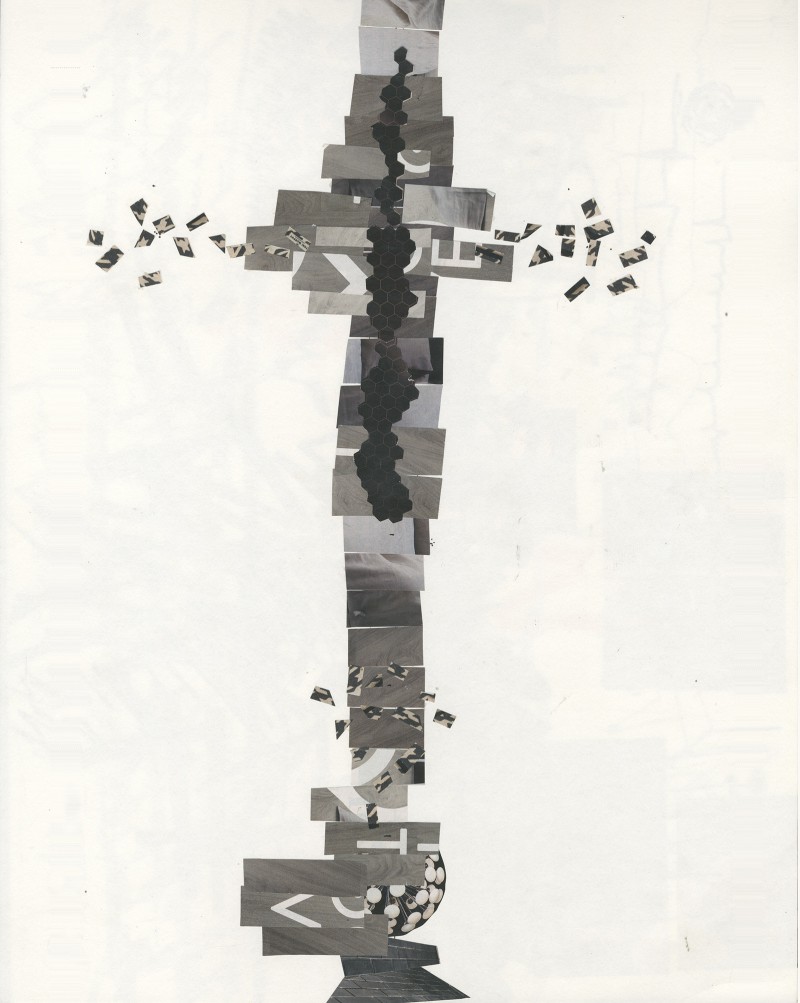

To deepen understanding and an appreciation of cross-disciplinary practice, the students participated in two workshops. The first, led by a pattern cutter (Figure 1), introduced the students to the processes of garment design using paper templates, cutting and stitching to create sculptural three-dimensional forms. The second workshop, led by a fashion and textiles tutor, resulted in the creation of paper garments and the investigation of containment at the scale of the body, the scale of the room and at the scale of the building, using drawing and photography. In addition, the students also experimented with approaches to representation informed by textile artists and ‘Drawn to Stitch’ (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

These creative and cross-disciplinary processes influenced all stages of the students’ projects: The sculptural garments that were initially designed to contain the body were expanded to create innovative interiors. Materials and processes, usually linked to fashion and textiles, inspired the students' designs and details; for example, the use of zips, weaving, stitching and pleating materials. The students also considered SCAP’s behavioural changes and applied their understanding to the selection of sustainable and recycled materials, which included the re-appropriation of discarded garments that were deconstructed and reassembled to create furniture and divisions of space (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Overall this project led to creative, ethical and well-substantiated proposals that exemplified the value of cross-disciplinary approaches.

Sound Space: Co-design and musical inspirations

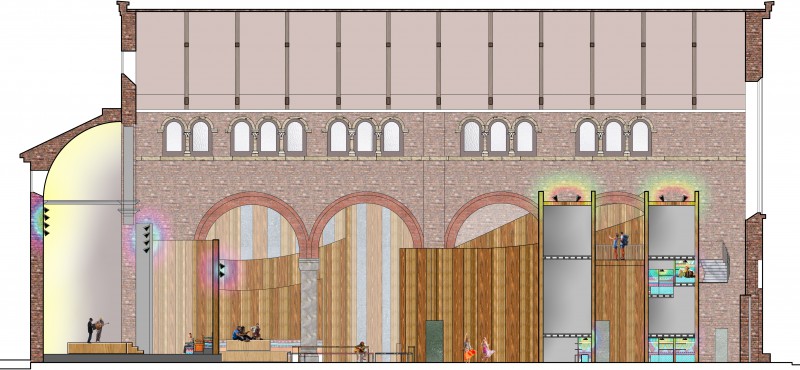

The last project in BA2, ‘Sound Space’, was located in St Agatha’s Church, an historic building set in the northern quarter of Portsmouth, which is an area of deprivation. The project brief set up two main challenges for the students: to develop a brief for the space that had music at its centre and to identify the common grounds between spatial design and music and discover how design concepts maybe generated from non-visual elements.

The first challenge was to develop a strategic brief and schedule of accommodation that responded to the needs of the local community. The second challenge applied to concept design where the fluid art of music became an integral part of the students’ concepts and design development. Students face difficulties in designing spaces that they have not experienced before and find it difficult to read precedents successfully, so quite often these two important processes depend on the students’ background and prior knowledge. To respond to this need and facilitate the generation of ideas the School organised two workshops, one at the brief writing stage and the other at the concept design.

Following the co-creation and co-design pattern increasingly evident in practice, the brief writing workshop was a collaboration with Portsmouth College, Portsmouth Music Services and Tonic Music for Mental Health. Students had to define the new function and what kind of spaces would be needed, but most importantly to demonstrate how young people and the wider community may benefit from such a facility. Through the collaboration the students had the opportunity to discuss the positive influence that engagement with music can have on communities and individuals’ socio-economics, well-being and happiness. To frame the investigation, Christopher Mahy from Portsmouth Music Services talked about the educational value of music, and Stephanie Langan from Tonic Music for Mental Health, discussed her work as a counsellor, underlining how music can help mental and physical well-being; this was particularly pertinent as mental health issues among young people are increasing.

Students had to define the new function and what kind of spaces would be needed, but most importantly to demonstrate how young people and the wider community may benefit from such a facility.

The most important part of the workshop though was the inclusion of the 6th form pupils from Portsmouth College who acted as the possible users and introduced the students to the practice of participatory design, focusing on the user and not just the clients’ needs or their own design aspirations. At the same time the pupils had a valuable insight into design studio in Higher Education.

The second workshop was based on a set of productive design operations, which triggered the production of sketches and physical models, examining the common grounds between music and spatial design. The workshop was divided in four parts in order to map a journey from the musical fluidity to a three-dimensional concept for a specific building. A small presentation preceded every activity introducing main concepts and generating discussions among students and tutors.

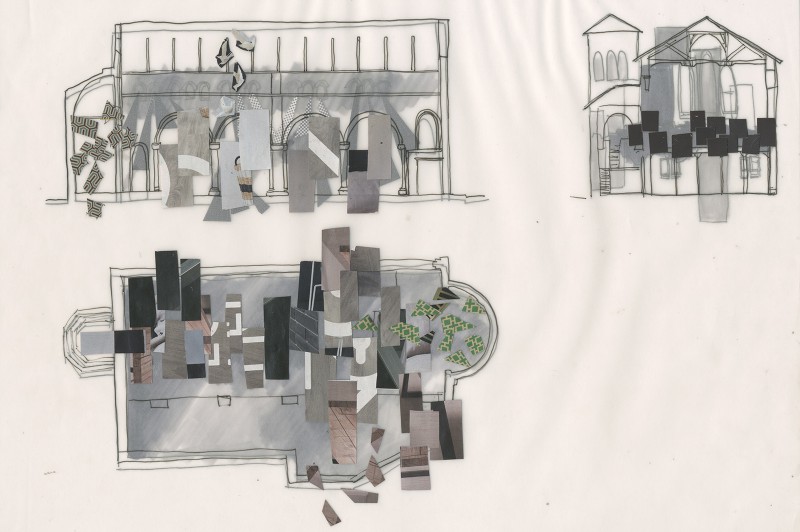

The first part called ‘Materialisation’ asked the students to create a collage or a painting based on music of their choice and were asked to reflect on the elements of the composition and the mood. The Second Part called ‘Organisation’ introduced musical terms as rhythm, repetitions, crescendos, sequence and musical colour, and asked students to revisit their collage and rearrange it according to the composition. Examples like John Cage’s musical scores , Xenaki’s work, Kandinsky and Klee , provided a framework for this activity (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Reflections

The learning paradigm of ‘process’ and ‘praxis’ at Portsmouth is supported by short, studio-based workshops, which help to create a dynamic and unpredictable learning environment that energises both students and lecturers, and enhances engagement and intrinsic motivation. These short projects encourage experimentation and risk-taking, processes that can be overlooked if students are concerned about marks and are rushing towards conclusions. Furthermore these instinctive approaches allow students to discover and process images and forms, which would have remained latent within more conventional approaches of concept generation.

The students are also encouraged to look beyond the conventions of their own discipline and to engage with alternative approaches to concept generation, design development and representation of ideas; a process of meaningful and analytical play that allows the student to sustain investigations, experiment and to understand themselves as designers.

These playful and cross-disciplinary approaches allow students to kick-start discussions, visualise theories and start making and designing; they are processes which enrich and enliven the early stages of a project and which lead to unpredictable, creative and substantiated outcomes.