The Complexity of Containment

ShareFirst year students often arrive at university with preconceived ideas of what Interior Design is, based on how the discipline is portrayed in popular culture. We challenge these ideas with ‘Container’, the first project students encounter in their education at RMIT University. Students are asked to design a container that responds to an object’s specific material and poetic qualities. Complexity arises as students are guided away from functional problem solving and, instead, must research material technologies, histories and poetics to generate new ways of forming interiors. This paper discusses the integrated teaching model we have developed, alongside case studies of student projects.

Introduction

“What is your definition of a container? A mountain can be a container but so can an eye dropper. The body is a container of sorts and, in English, we refer to ships as vessels. All to say, it’s a tricky question: What is a container?”[1]

Conventional interiors are easy to recognise. They are parcels of contained space, typically the insides of buildings. But the discipline of Interior Design is limited by this conventional understanding of interiors contained within walls, an issue we try to open up during the first year of a student’s education. A conversation creates an interior; so does an umbrella opened to fend off the rain. Our clothing provides pockets of interior space that are always close to hand. Spaces such as the pocket suggest a conception of interiors at the scale of objects, and designed to suit.

Our first year project ‘Container’ challenges students to produce unconventional interiors for particular objects. [2] They begin with a very general description of an object, selected by lucky dip. Examples of these descriptions include: ‘a piece of fruit’, ‘something to light a fire with’, ‘currency’ or ‘a ball’. Students’ first design decision was to choose a specific instance of this object. After reflection and research, students nominated pineapples, a zippo lighter gifted to them, five handfuls of rice (payment for a day’s work in 18th century Philippines) or a toy ball – creating a diverse and unusual range of objects. Each student then undertook a process of research and analysis to identify the key poetic qualities of their chosen object in order to design a container for it. We prompted student’s understanding of poetics[3] through a series of questions: What are your item’s material qualities? How is it made? What is its history? How does it move, or feel? What does it offer? How does it operate? At the end of this first class each student had a unique brief; to design a container for their particular object that articulates its poetics and the poetics of containment. We were already a long way away from designing the inside buildings!

An integrated teaching model

The six-week Container project emphasises physical modelling and material experimentation, and exposes students to design as an iterative process. Beginning with quick physical models constructed from materials like paper, card, thread, masking tape and clay, students experimented with strategies of containment and forms that expressed the poetics of containing their particular object. Over the following weeks these models were discussed, re-made and refined. The students’ material choices developed in parallel with the formal experiments, and responded to the particularities of each object and its poetics. The final outcomes of the project were one finely crafted container and one sectional presentation drawing, both at 1:1 scale.

Working towards these outcomes did not occur only in Design Studio classes. In their Technology subject students were introduced to processes of prototyping, hands-on material discovery of structures and forms through playful experimentation, all the while reinforcing ideas of design development as an iterative process. Communication classes covered photography, model-making and drawing skills. These skills were brought together in the making of a single project, much like in professional design practice. As Inger Mewburn describes, design practice is “characterized by uncertainty, complexity, instability, uniqueness and value conflicts.”[4] These challenges were built into the teaching structure of Container. Students developed their design expertise through the iterative making of models and drawings, with materiality playing a key role in this process. Design expertise comes about by learning to listen to the ways a particular iteration ‘talks back’ and suggests the next steps to take.[5]

We made the connections between these three subjects explicit, leading to what we call an integrated model of teaching. This is a pedagogical approach where students are working on a single project that spans across their various subjects. The value in doing this was two-fold. First, it reduced the quantity of work for students as the central design ideas could develop across all their classes. Secondly, and more significantly, working on one project across these different subjects allowed students to understand the connections between different skills and modes of enquiry, and how each approach can push a design forward.

The integrated model also helped us emphasise to the students the value of sharing resources and supporting each other as a community of learners. In doing so, our approach was similar to what Ashraf Salama calls “systemic pedagogy”, a system of teaching focused on the “acquisition of holistic knowledge.”[6] According to Salama this proceeds from the “basic and well-proven premise that learning best takes place when:

- subjects are learned by teaching them to oneself;

- subjects are assimilated by teaching them to others;

- skills are learned through demonstration and instruction;

- fundamentals are attained in seminar discussions guided by one specialised in the relevant area; and

- certain skills are acquired in groups while others are attained individually.”[7]

Our emphasis on in-class making in Design Studio classes, supported by short demonstrations and group discussions of the student work, was integrated with the skills acquired in Technology and Communication classes. This helped students to acquire holistic knowledge that reflects how designers actually work in practice.

Studio teaching is itself an iterative process and there is room to further tighten the connections between subjects in future versions of the project. In particular, a series of classes in the communication subject will focus on the significance of sectional drawing for interior designers. These classes will also equip students with specific skills and techniques for better resolving the sectional drawings of their containers.

Student projects: some case studies

Our first year cohort is well over 100 students, but a short discussion of some selected projects will give a sense of the diversity of materials and ideas that students used in making their containers, and the conceptual complexities that were opened up.

Charlotte Paule created a container for a corkscrew, working with a solid block of cork ingeniously sourced from a yoga equipment retailer (Figure 1).

Other students worked with ideas of motion, and the container as space to be enjoyed by the object it housed. Elisa Yimin Xu’s ‘Toy ball amusement park’ created an orbital pathway along which a small ball could circulate (Figure 2).

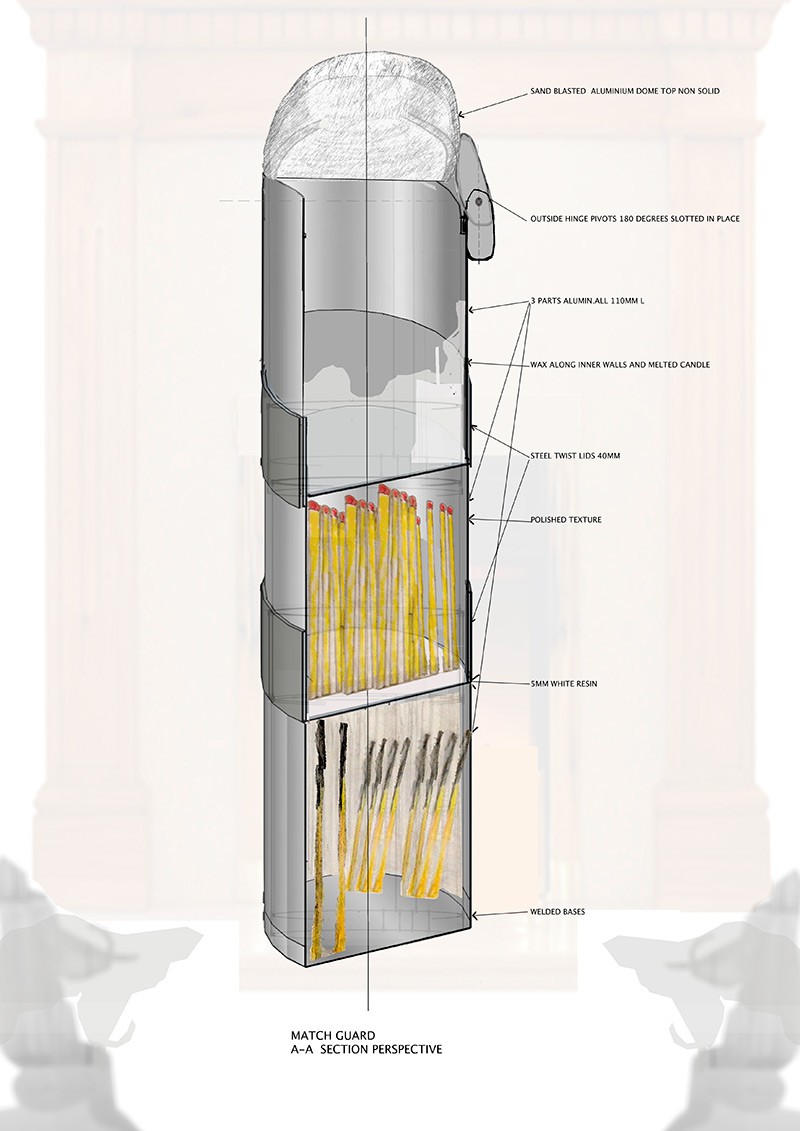

The performative quality of the container and object were also evident in ‘Match guard’ a container for 45 extra-long matches by Ilana Leber (Figures 3 and 4).

The container exaggerated the match form and was organised into three sections. The middle section held fresh matches, which could then be struck against the side of the metal tube. A top section housed a candle and included a cover to extinguish the candle as required. Once the candle in the top section was lit, dead matches were stored in the lower section. In Leber’s project, there is an interplay between use and containment, suggesting ideas of Interior Design concerned with time and performance as well as space.

Siobhan McCarthy’s ‘Piña futura’ (Figure 5) moved beyond the idea of a container as a void space enclosing a particular object and instead offered an idea of container as plenum. McCarthy’s pineapple was cast from a range of semi-synthetic, edible pineapple gel materials, which she developed through a process of remarkable and meticulous material experimentation. Her project proposed a future of food production and consumption in response to the traditional farming of pineapples where each plant produces only a single fruit each year. ‘Piña futura’ also acknowledged the pineapple as a sculptural form in reference to its 18th century use an exotic object and symbol of wealth.

Making the work public

Immediately after presentations and reviews of their final containers and drawings, all the projects were brought together for a student-organised exhibition that celebrated the diversity of work and engaged a wider audience (Figure 6).

We consider exhibition-making as a practical way for Interior Design students to develop a valuable set of skills. These include thinking spatially, curation, sequencing of experiences, team work, communication and the idea of producing and hosting an event. Students organised a bar and food, a digital catalogue, and a promotional poster. The intense time constraint meant students worked together, made decisions quickly, and gained confidence – all valuable in creating a supportive “community of learning”[8] and for the remainder of their studies and later work in professional practice.

In making the work public, students receive feedback from a wider audience, and learn to articulate their work to fellow students, family and friends, and the wider design community. Exhibiting their work encourages students to understand the value of their work to a public audience, away from the narratives around the work that are constructed within a design studio teaching environment. Despite these benefits, there is surprisingly little literature on the pedagogical value of exhibition-making.

Conclusion

The integrated teaching model introduced in ‘Container’ was extended and strengthened in the subsequent project that students undertook. This project utilised an even tighter connection between Design Studio and Technology classes. Students began with physical model making (reinforcing the skills acquired in ‘Container’) before being introduced to digital 3D modelling in Rhino. They worked with this software across Studio and Technology classes to develop their designs. Once again, the integrated model was valuable in eliminating the duplication of work, enabling students more time for in-depth investigation. Time spent on developing their digital models had value for both their Design Studio and Technology classes. Personal investment in the design projects also motivated students to extend their technical skills in order to better model their designs. This predominantly digital workflow culminated in a set of presentation drawings that showed a huge advance in skills compared those produced for ‘Container’ (but this is a story for another time).

The diversity of responses to the ‘Container’ project greatly expanded students’ material skills, and shifted their thinking of interiors away from the conventional tropes of design for residential, commercial and hospitality spaces contained within buildings. Instead, interiors were understood as being formed through material, spatial and poetic relations, dependent on time, motion and performativity.

Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of this model of teaching has been seeing the students form an inclusive and supportive community, with a high degree of independent learning skills. It will be exciting to see how this group of students continues to progress through their education and into the world of practice.