Unveiling. Identity and interiors.

ShareSome buildings are considered without interiors, their majestic and monumental facades concealing their interior spaces and their history inhibiting their adaptation. This paper addresses the Colonie – a legacy of Italy’s Fascist past - which through a process of survey, the consultation of historical documents, and their reconstruction through drawings and maquettes, highlights unexpected ways of remodelling the Colonie’s interiors as inhabitable spaces. The student projects described here testify to the double nature of these places and allow them to be reinvented, overwriting the deeply problematic memories that they transmit, through the identification of new narratives of use and inhabitation.

Totalitarian regimes of the beginning of the last century, tried to control every aspect of human life, using architecture as a tool to communicate new ideas about education, health and family life. In Italy the Fascist Regime developed a special programme focused on children - educated as New Italians devoted to the Nation, they were meant to become masculine soldiers or prolific mothers. During the long summer break from school, a special institution took care of their health and growth. The Colonie [1] were Summer Camps built throughout Italy, along the seaside, on the slopes of the Alps and the Apennines, and, for daily use, around city centres. These buildings were designed carefully to organise the daily routine of the children that, in groups, never left alone, moved together through the spaces and the different activities.

Abandoned after WWII, the Colonie were forgotten – their difficult historical legacy has prevented them from being re-used. The research I carried out sheds light on how these interiors were designed and unveils their double nature - they emerge from the landscape as icons of political power but their interiors are very sensible, designed carefully around the everyday rhythms of human life.

Knowledge/identity: reading the existing

The two buildings are high up in the Scrivia Valley. Montemaggio in particular is perfectly visible for dozens of kilometres - its unique identity written in its white façade, with the asymmetric tower originally bearing inscriptions that proclaim Fascist ideas. The interiors at Montemaggio are the object of systematic vandalism. People have entered the building - unprotected and unprotectable because of its position - and systematically destroyed it: doors, windows, partitions and false ceilings. This is a relentless process that nobody is able to control. The interior, the “soft” part of the building, translating fascist ideas about taking care of children, is hidden and largely forgotten.

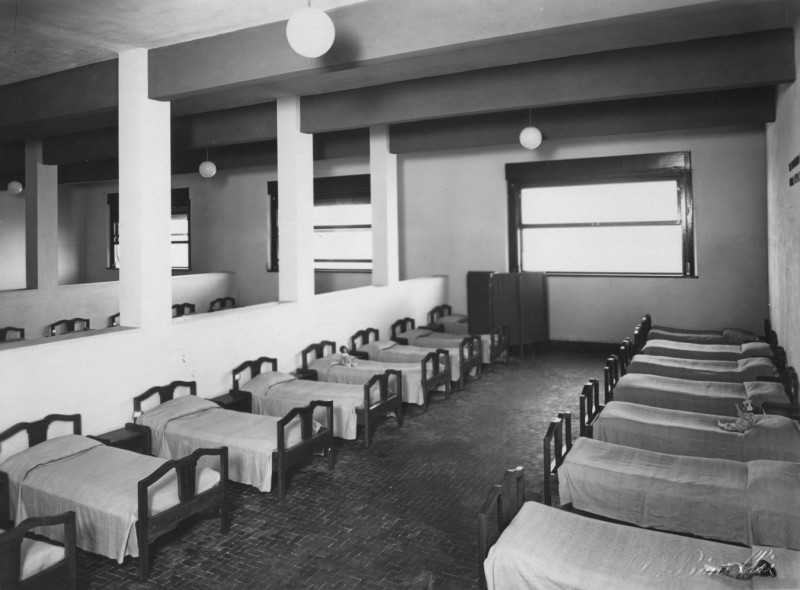

From our historical and archival research we understood that the now semi-abandoned volumes were coloured and designed in detail, with bespoke furniture. In the dining hall ‘all tables are blue: they are made in the upper part of a material composed by slate and nitrocellulose, washable and unbreakable; they are edged with steel, to protect corners from dents and cuts. Dishes are all yellow: every soup plate is embossed with the initials of the Fascist Federation of Genoa in golden letters. Cutlery: spoons, knifes and forks are of a brand new type, exhibited this year for the first time in the Triennale of Milan.’[3]

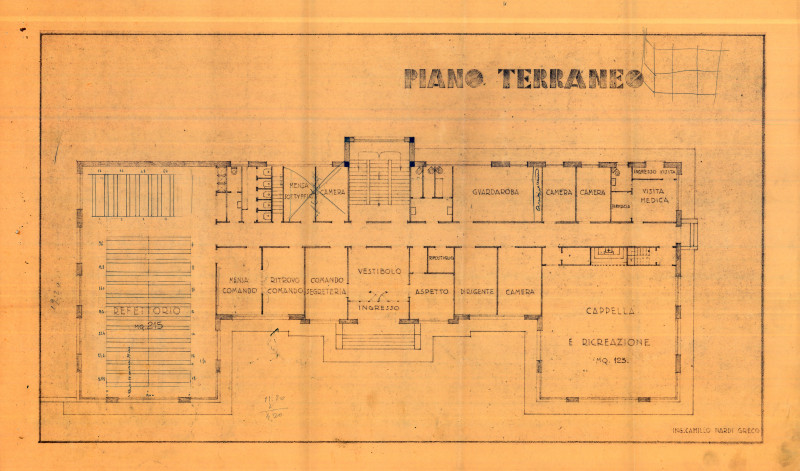

The process of documenting and interpreting the identity of the Colonie, initially uses traditional methods, such as direct survey and the consultation of historical sources. Their reconstruction, through drawings and three-dimensional maquettes, highlight unexpected opportunities to re-use their inhabitable spaces. The circulation of the building is one of the main features and is designed to direct children from the outer garden, to the entrance hall and stairwell.

Entering Renesso (and to some extent Montemaggio) means crossing a set of interconnected spaces, perfectly controlled in their design and construction. From the outer open space, children had to reach the raised ground floor, climbing up eight steps that were built and finished using bricks. Upon reaching the landing they had to cross a double, full height door in chestnut, framed by decorations in a local green marble; an inner landing with the inscription A.XI [4] framed by white tiles on a field of grey tiles; and a second glazed door, before arriving at the entrance hall. The floor finish is continuous throughout, and leads to the main staircase. Concrete transverse beams and a large geometrical lamp, articulate the ceiling. The three flights of stairs are made of three different materials and different colours: red for the metal banister, black for the treads, the skirting, and the top of the opaque part of the parapet, and white for the plaster of the walls and risers. The full space is perfectly lighted by two big rectangular windows.

The identity of these buildings is written in their material form. As in all arts, the signifier (the material form and appearance of the work) and the signified (the cognitive, intellectual and emotional content), are embodied and convey their meaning. The reconstructed plans and sections highlight the unexpected and precise control of all the elements of architecture, from the layout to detailing and materiality.

Old/new: design strategies

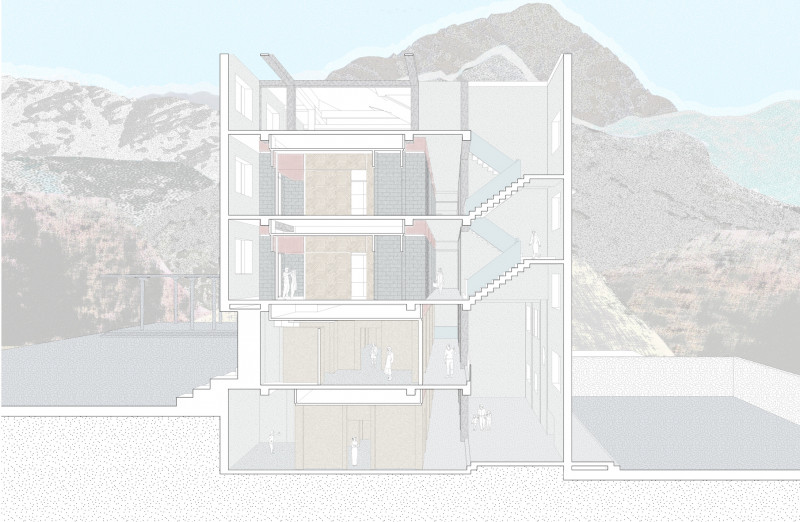

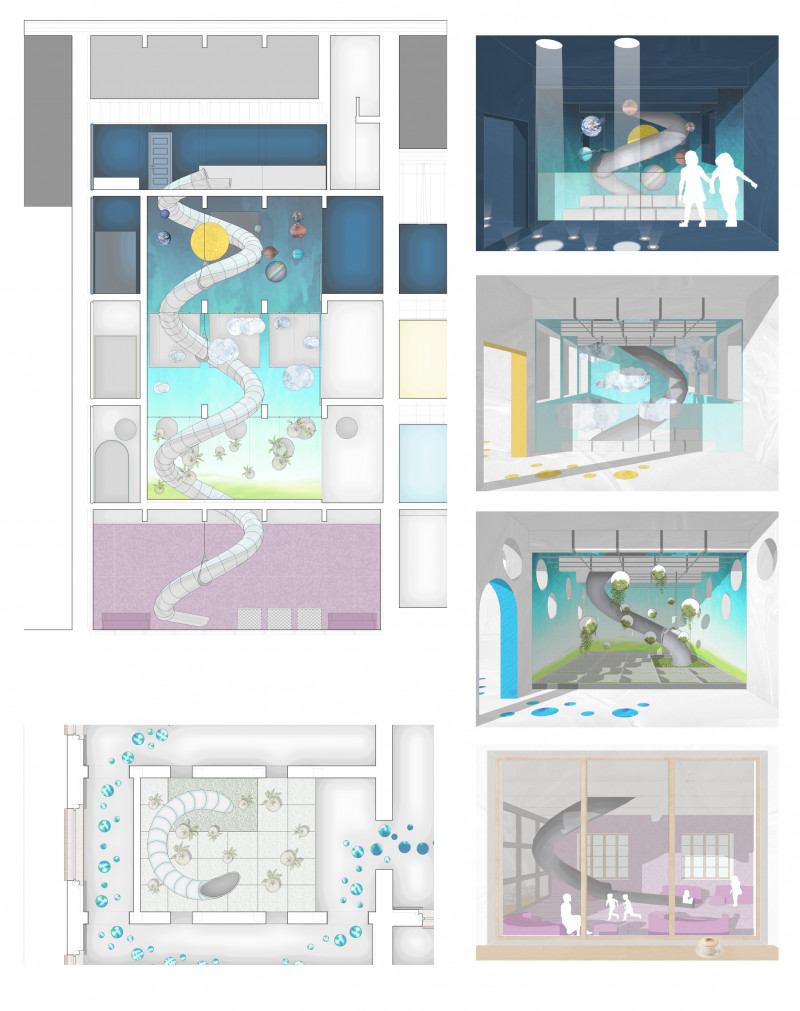

Following this approach, the projects developed for the Studio, and deepened in a Master's degree thesis, have continued to imagine the Colonie as a place to take care of young people. One approach was to maintain and reinforce a selected feature: the tension in height of Montemaggio, expressed by the higher right tower, can be seen in the project for a Science Museum for Children. The whole height of the tower becomes visible thanks to superimposed voids on different levels, crossed by a transparent slide bringing young guests back from the higher level of the exhibition to the entrance floor.[5]

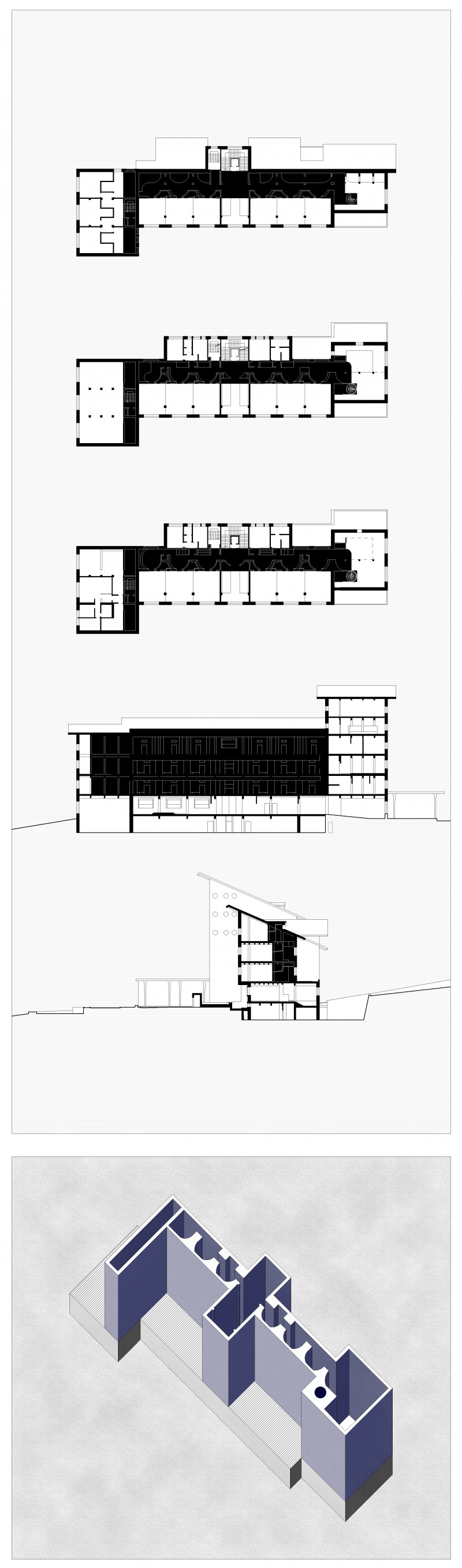

Another strategy was to recognize and evolve a feature, in this instance the strict functionalism of the Colonie and the organization of the circulation of large groups of children - translated into long, straight corridors along the rear façade of Montemaggio. The feature is highlighted and transformed by modifying the corridors in order to disrupt and diversify the rhythm of the circulation.[6]

A last approach was to recognize and exceed a feature: the strict symmetry of the dormitory of Montemaggio is completely overtaken by the new distribution of space, moving the entrance of the art and performance area to the side of the building.[7]

Hidden/unveiled: a possible conclusion

Every design opportunity comes from the comprehension of the identity of the building. In the specific case of the Colonie, it means to unveil what is hidden, invisible or concealed, yet existing. This process allows us to dissect different layers of meaning in order to bring to light its basic, fundamental identity.

Interiors are a part of this identity, but not the main, nor the unique one: they are one of the actors in a play. The presence of opposite attitudes in this specific typology of building, monumental and intimate, makes their recognition difficult. Every interpretation, for preservation or for re-use, has to accept the nature of the building, working not only on commonly recognized features, but also on the ones usually undervalued or neglected, expressed by the complex material forms of architecture.