Transforming Learning, Making Space

ShareHaving introduced an emphasis on 1:1 physical making into the level 5 unit Spatial Identities on the Interior Architecture and Design course at UCA Farnham, we conducted a piece of research on students’ learning experiences on the unit, using focus group data and grounded-theory-informed qualitative analysis to help isolate key elements in students’ learning. The structure project set was a shared brief between level 5 students at the University for the Creative Arts and the University of the West of England. The cross-institutional learning partnership is a new learning strategy and this paper investigates how it impacted on the student learning experience.

Introduction

As two Senior Fellows of the Higher Education Academy, we initially saw the collaboration between UWE and UCA as an interesting opportunity for colleagues to share knowledge and practice in teaching and learning. However, to justify a cross-institutional exercise involving considerable planning, expense, and logistical arrangements, author 1 (Gower) needed to see and demonstrate clear benefit to the UCA students; the author 2 (Kasket), a psychologist with an interest in design education and experience in research methodology, was brought in to help shape and carry out the project.

Because the project had not been run before at UCA, there was no baseline against which to measure the impact of the UWE collaboration, and like-for-like comparison between UWE and UCA was difficult due to differences in briefs. Both sets of students needed to produce illuminated structures that could be occupied, but the UCA brief retained tensegrity and swapped geodesic for gridshell. The UCA structures also required to serve as exhibition spaces, which had to meet the requirements of clients, i.e., the textiles and screen-printing departments; and would be located outside rather than inside, in midwinter, in two external courtyards on the Farnham campus.

The aim of this research, therefore, was not to compare like with like, nor to measure these students’ performance against a non-existent baseline. Instead, we decided to investigate (a) whether the learning gains for students seemed to outweigh the practical costs of the collaboration, and (b) how learning was enhanced through the exercise for both students and tutors. We used a multi-strategy approach to capture students’ perceptions of how their learning was transformed through interacting with other student designers who had recently been makers.

Methodology

Participants: Participants were 13 level 5 students undertaking ‘Display Part 1 – Structure’ project in the Spatial Identities unit on the Interior Architecture and Design course at UCA Farnham.

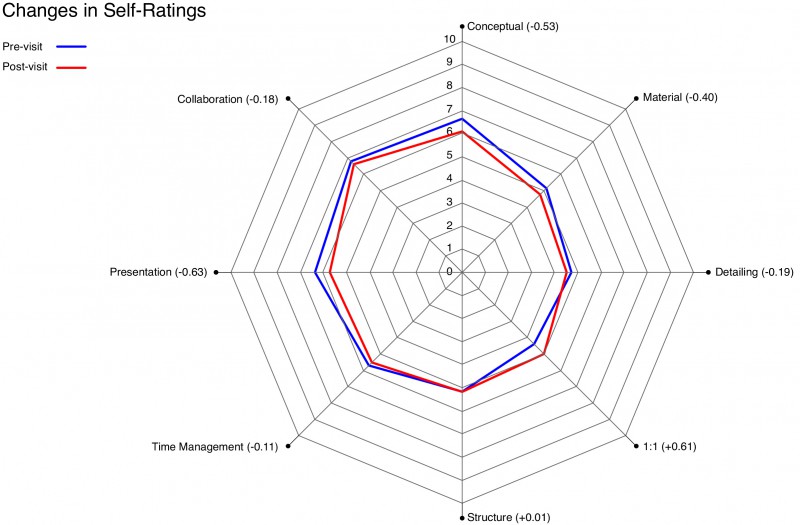

Data Collection: To measure quantitative change, students used a blank 10-point radar diagram to plot pre-UWE-visit and post-UWE-visit self-ratings of their confidence (0 = no confidence, 10 = most confidence possible) on eight skills perceived necessary for successful completion of the brief. This allowed for quick visual assessment of responses and a relatively non-hierarchical presentation of the skills. Chronologically, the order was first brief, then pre-visit data collection, then UWE visit, then post-visit data collection, then the first significant lecture of the unit, then delivery of the second, developed UCA brief, then the start of UCA students’ own design process, and finally focus group.

To capture qualitative data, students wrote comments on their self-assessment about their expectations for their performance and the project overall. Kasket also conducted two 45-minute focus groups with tensegrity and gridshell groups separately, several weeks after the UWE visit. With the eight skills displayed on a whiteboard to provide focus, the researcher invited them to describe and reflect on their experiences, following students’ leads in prompting for more detail, description and clarification. The focus groups were recorded, transcribed, anonymised, and shared with Gower for independent and then joint inductive analysis of self-reflections and focus group data.

Ethics: Institutional ethical approval at UCA was obtained. Students were then informed about the nature and purpose of the research, assured that their data would be anonymous and that refusal to participate would not affect their assessment, briefed on how the results would be used, and provided opportunities to ask questions before giving consent.

Findings and Discussion

Quantitative Data

Looking at the quantitative data in isolation, we saw that the subjective immediate impact of the visit to UWE was negligible (Figure 1). In six out of eight areas, there was a slight drop in students’ ratings from pre-visit to post-visit; however, crucially for this particular project, there was a noticeable increase in students’ confidence at working with 1:1 scale, which increased by 0.61 points. The largest decreases in confidence were in the areas of presentation skills and conceptual thinking, indicating that the visit slightly diminished UCA students’ sense of their own current capabilities.

We hoped that the qualitative data analysis might yield further information as to whether the visit had indeed added value in terms of learning gains, despite the quantitative dip in confidence. We extracted two main themes: “finding flow” and “students as designers and users”.

Qualitative Theme 1: Finding Flow

The prospect of working at 1:1 represented a significant challenge for these students, the majority of whom only had existing skills and knowledge around drawing and model making, skills that represented a form of ritual knowledge [1] : within the students’ grasp and fund of existing experience, but at risk of being disconnected what happens in industry. The majority of students recalled their initial apprehension about being able to achieve the structures project independently, citing working at 1:1 as a focal point for their anxiety.

Person 1 (gridshell): I was expecting a high level of complexity…working 1:1 compared to models. I was a bit concerned, a bit worried that it would be a struggle…. without seeing UWE, and what they did, and having no prior knowledge of doing 1:1 and working with these joints, it would have been really, really scary.

Person 3 (tensegrity): I think it’s just how big it is, the scale of it….it’s just the fact that you’re working at a very big scale in comparison to what we’ve been used to.

After the visit, students described how critical the UWE visit had been in addressing self-doubt and assuaging anxiety. Reassurance came in a variety of forms, one of which was simply observing that a group of similar students had achieved a successful outcome within the time scale.

Person 1 (gridshell): Obviously going to UWE, it was like, this is doable. This isn’t this, like, imaginative fear of, you know, can I do this??

Person 1 (tensegrity): I think for me it’s like, less scary now…. Now I feel much better. Doable. The other group did it.

Post-visit self-assessment: By being at the UWE visit, I got a much clearer understanding of how this project could be constructed.

Even more important than observing the outcome, however, was the opportunity to hear about the process for UWE students. UCA students described coming away from the visit with more realistic expectations, relieved that it was possible to make mistakes and still succeed in the end.

Person 3 (gridshell): So knowing that they’ve had troubles and they’ve overcome them and that’s what they’ve ended up with, it’s quite reassuring to know that they have had those problems, we’re probably going to have those problems, but that’s fine, then you’ll get there.

Person 1 (gridshell): Personally, actually, it gave me confidence, because it was like, okay, now we can be prepared, because they’re saying, this can happen, like, you can have a complete collapse a few days before, so it’s like, okay, although it was kind of, oh god, now we’re prepared, so we know that it might collapse a day before presentation.

Person 1 (tensegrity): [It] was nice to see…they were talking about their faults in their journey, and it was, we’ve done this, you shouldn’t do that.

Post-visit self-assessment: Seeing and hearing the students explain their processes made me understand materials and construction of the structure much better.

The reassurance of the brief’s achievability was balanced against another kind of anxiety – the pressure to do better than the UWE students. Rather than this anxiety’s being crippling, however, it was expressed as a driving force to do well.

Person 4 (gridshell): Yeah, I would probably split it into, like, feeling maybe 20% reassured and 80% more pressure.

Person 3 (tensegrity): We’re at a bigger advantage because we’ve seen theirs before we’ve even done ours….I’ve got to either do something like that or improve on that, or do something a little bit different…[the UWE students] are probably thinking, well now [the UCA students have] seen ours, so they’ve got to be really good.

Person 1 (gridshell): It’s a competition….You just want to achieve more, you want to do more research, you want to learn more skills to just, for your craft to become more refined, you know, this project, it’s almost like working 110% just to prove a point.

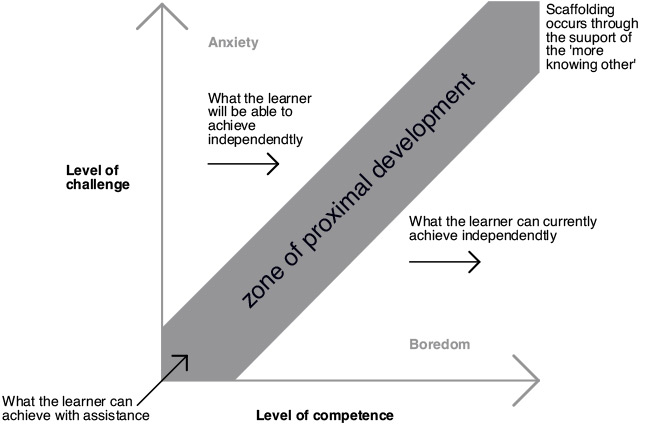

The students’ description of their experience maps perfectly onto the learning concepts captured in Figure 2. They were competent at model-making and drawing, potentially placing them in the “boredom” zone of skills that they could already readily achieve independently. This 1:1 structures brief, however, represented a jump into the unknown and a significant increase in challenge level; this was associated with considerable anxiety and uncertainty. Had they not received adequate scaffolding from more skilled others, the UCA students believed that they would have struggled to achieve the brief independently.

By interacting with UWE students at their critique, however, UCA students were able to bridge “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving…in collaboration with more capable peers” [2] This is the “zone of proximal development” [3] as shown in Figure 2, a “flow channel” [4] where challenges and the capacities to meet those challenges are aligned. The UWE visit was the right support at the right time to meet the needs of the UCA learners, and students’ descriptions of their experience clearly matched the characteristics of flow states, for example, the “sense that one can control one’s actions; that is, a sense that one can in principle deal with the situation because one knows how to respond to whatever happens next” [5]. The role of the cross-institutional collaboration in UCA students’ “finding their flow” is, in and of itself, more than sufficient reason to repeat the exercise in future.

Qualitative Theme 2: Students as designers and users

Interior designers create spaces that have use and function in addition to being structurally sound. The conviction that function should be at the heart of interior designers’ thinking was a driving force behind adapting the shared structures brief to incorporate use, in the form of display. Interestingly, however, we did not include use and function on the radar graph designed for this project, although it may have been implied by “conceptual thinking”; instead, both the graph and the initial project brief focused students’ attention towards the more static, concrete areas of skill and knowledge such as 1:1, structure, and detailing, and other dynamic aspects of the project such as time management, presentation and collaboration (which students seemed to read as collaboration within their working groups, not as collaboration with a client). If ‘use’ is so key – the whole reason behind the expansion of the UCA brief – why were ‘use’ and ‘function’ neglected? Is this an illustration of educators' knowledge being so ingrained that we assumed it to be obvious to learners? That assumption – combined with the fact that explicit consideration of function/use was not modelled by the UWE projects - could have been problematic for the less experienced UCA students, already on a steep learning curve. Did the UWE visit seem to help these student designers experience and think about the spaces like users, even with few prompts to do so?

Both comparison of the pre-test and post-test questionnaires, and data from the focus groups, seem to indicate that this is the case. (NB: The post-test questionnaire was administered before a lecture on function, occupation, experience and use; the focus groups occurred after this lecture.) One student, who had expected to learn about “working better with larger scales [and] mak[ing] more models” before the UWE visit, said after the visit: “I now know first-hand how physically manifested ideas can directly affect people”.

By employing the adjective “first-hand”, this student refers to experiencing structures from the vantage point of the user. She describes structures as “physically manifested ideas”, neatly capturing the transition from representation to realisation. The word “now” implies that the student had not fully grasped this beforehand; also noticeable is the phrase “directly affected”, contrasted with the more removed and “indirect” experience of models and drawings.

Another student briefly refers to the experience of the user in her pre-visit assessment, when describing the need to “make [the space] cosy” – underscoring the importance of users being able to inhabit or utilise spaces comfortably. After the visit, however, the student is more explicit about her desire to understand more about designing spaces that work for users:

Functioning in a structure – how to effectively use a space, that is what I want to learn more in design.

Another student begins her pre-visit comments by speaking about materials, but then rapidly moves onto function, demonstrating her awareness of the context of the structures:

Expand material knowledge, how it actually functions in real life, different weather conditions. Need to make a structure that will actually stand up on its own rather than just a model at small scale.

This student embeds her mention of material knowledge within considerations of function, showing that she is already seeing form and function as indivisible from one another. She also shows recognition that this is a step up from “just” a model – conveying that while models might be necessary things, they are not enough to capture a real experience. This can only be achieved through actually (synonymous with “really”) producing something that can stand up on its own – that is, it will carry on and have a function without the designer, as other users interact with it. After the visit, this student homed in even further on the specifics of context for the UCA project.

[M]aterials…will [need to] fare well outside…in January, need to be cold- wind-, rain-resistant/proof. The structure will need to stand up on its own. Will it need to be anchored, or will it be strong enough structurally to stand up on its own? Need to also think about how the space will be used and whether the structure helps or hinders the action.

The post-visit commentary goes beyond mention of weather generically and has become specific to midwinter in the UK. The need to stand up on its own is reiterated, but the visit has prompted the student to think more about this – for example, whether it will need anchoring. The student is now speaking about the use of the space and how the structure will facilitate use, or get in its way. The impact of the visit has been to take the student from an initial understanding to a further elaboration of the importance of thinking about how the structure will be rendered usable.

There are two occupations of interiors: the designer, and the user. In the visit, UCA students were able to hear about the UWE students’ experiences of being designers, but also witnessed and shared the experience of being users.

When students move to the construction phase of their projects they build a relationship with their own structures through the experience of making, and the notion of occupation is reinforced through their own experience as users of those structures; however, the UWE visit gave UCA students a head start on this experience, allowing more focus on occupation from the outset. This was often expressed in the focus groups as new knowledge, something that still feels somewhat surprising, outside of the “normal” practice or understanding.

Person 3 (tensegrity): Normally when you’re model making, you think, not I’m going to fit inside it, but potentially there’s going to be someone that should be inserted. We put little people in there and we don’t think about how that it is when you’re actually meant to be the person standing in there until you get to the 1:1.

This student is describing a common experience. Making at smaller scales may be focused on form and volumes, and can become disconnected from the understanding that the spaces are to be experienced. The above student expresses this personal disconnection clearly, through third-person language: “there’s going to be someone [i.e., not me]…inserted” and “we put little people [i.e., unlike me] in there”. In models at 1:100 or 1:50, the figure being described is a passive object, only there to give scale. Making at scales smaller than 1:1 indicates, in this case, a separation between a designer and user by rendering the perception of spaces as uninhabited and unused. Other students also described how physical making of a structure at 1:1 has thrown them into the cross-current between design and use.

Person 4 (gridshell): [W]e’ve never done 1:1, we’ve only done just smaller models. So, we’ve never actually felt how the space feels, we’ve never actually seen what we’ve made in real life, it’s always been in models, so working 1:1 you get more of a feel for what you’ve designed, and it may feel completely different to what you want it to be.

This student speaks repeatedly of “feel” as an apparently active ingredient in changing her perceptions, expanding her horizons beyond “just” smaller models – employing the word “just” conveys a sense that she is now thinking about models as insufficient. “We’ve never actually felt how the space feels”, she says. “[W]orking 1:1 you get more of a feel.” This student expresses how the “feel” that she derives from using the space might be a corrective, an incentive to change design direction: “it may feel completely different to what you want it to be”. Here, she captures how making serves as the practical analysis of how something works – an analysis that is not possible during other design processes, including conceptualisation, drawing, and model making.

Conclusion

We believe that the accounts of these students are evidence of how making at 1:1 on an interiors course adds value to the learning and teaching process, giving tutors insights into how and when students learn. At a time when UCA students were anxious about an imminent, significant step-change in their learning, the UWE visit not only provided appropriate scaffolding for that step, but also represented an early reinforcement of learners’ understanding of experience and occupation. The visit enabled UCA students to see and hear other students, like themselves, making strong connections between making and use, and they shared that experience with them. This already seems to have accelerated their knowledge acquisition and will likely be transformative in their current and future design practice.