The Front Door: Interfacing Interior and Exterior Domains

ShareCourse: History of the Built Interior, 15th – 20th Centuries Level of Delivery: 1st Year Graduate Students (MFA Interior Design, Parsons The New School for Design) History of the Built Interior, 15th-20th Centuries is a semester-long curriculum course for the Masters of Fine Arts in Interior Design program at Parsons The New School for Design. The course is structured as two-thirds lecture series and one-third discussion session. The lectures focus on the history and development of Interior Design as a discipline, while the discussion sessions aim to bring these historical concepts into present day design thinking. The course’s online discussion forum serves as a platform for academic prompts and student thought and questioning. The topics considered in this forum often develop into the foundation for the following weeks’ in-class discussion sessions. In this case, the interactive dialogue was progressed into a vibrant in-class discussion about the role of the front door in today’s homes, and serves as the jumping off point for this paper, The Front Door: Interfacing Interior and Exterior Domains.

A residence’s front door is both literal and metaphorical in its existence. It is simultaneously the primary method of entry into a dwelling, and a symbolic representation of that dwelling itself. It is inextricably linked to the character of a house, belonging both to the architectural facade and to domestic life inside the home. In essence, the front door is a three-dimensional edge that is both interior and exterior — yet neither at the same time — working as a threshold that divides, connects and negotiates the relationship between two domains.

This paper will evaluate how the front door – through its situation in space, its relationship to other front doors in a community, its methods of use, and its material and design-based qualities – can be used as a tool through which we can better understand the socioeconomic behaviors of a neighborhood. Furthermore, this paper will explore how a singular component of interior design can inform the everyday experiences of individuals within a community, while simultaneously allowing us to examine the overall character of a community itself.

Situation in Space

On a summer evening many years ago, I sat alongside my college mentor, swaying to and fro in a rocking chair on her front porch. She reminisced about how her home had evolved, how she and her husband had carefully selected the property and the neighborhood before deciding to purchase their first house a decade prior. “Check to see if there are front porches,” she advised. I looked at her, unsure at first of what she was implying. “They indicate how a neighborhood functions. If most of the houses have a front porch, it is more likely that you will see your neighbors outside of their homes, and will afford you the opportunity to interact with them. So often nowadays, families choose to spend their outdoor time in the privacy of their own backyards.”

It was not until years later, when studying and teaching interior design, that the profundity of her words was fully realized. The front porch can be thought of as an extension of the front door, a fascinating middle ground that is both interior and exterior, and that negotiates the realm between the public space of the street and the private space of the domestic interior. When a front door is situated so as to share the same surface edges as a porch, inhabitants are drawn out of their house through the front façade, consequently facilitating their interactions with nearby neighbors. This placement softens the transition between interior and exterior domains, blurring the boundary between public and private life.

If there is not a front porch, how is the front door positioned? Is it still part of the front facade? If so, does it sit on the ground, or is it situated above eye level, atop a flight of stairs, so that the incomer is looking up at the resident (and the resident peering down at the incomer)? Is it located directly off of the sidewalk, or is it set far behind the variance line, heightening the experience of a visitor approaching the house? Is there a gate or fence separating the public walk from the front entry? Is the front door visible from the street? (Figure 1)

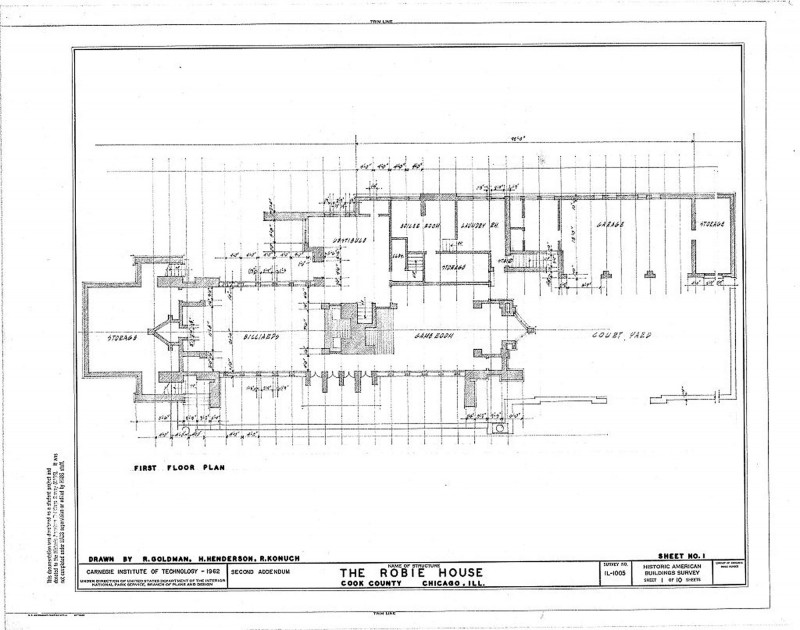

The situation of the front door in space is a topic that has been long explored throughout design history. Frank Lloyd Wright was iconic in his purposeful hiding of the entryway from street view, intent on highlighting the architectural experience and exaggerating the progression from public to private realm. For those inside the home, his veiling of the front door afforded more privacy, magnifying the disparity between the two domains. His drawings of the Robie House – both the floor plans and elevations – show his opposition to making the front door the focal point of the home; one must study the plans to decipher the point of entry, while the elevations illustrate his intention to camouflage the front door with the façade (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Other residences featured in design literature portray varying philosophies on the proper placement of a house’s front door. Photographs in Architectural Digest, for instance, showcase front doors centered on the main axis of a residence’s driveway, which itself is centered on the property, thereby making the front door the most visible and prominent element of the home.

While the placement of one front door can help us understand the lifestyle of a particular household, it alone does not accomplish enough in allowing us to understand the character of an entire community. As suggested by my mentor, there is a crucial collective element when determining the character of a neighborhood. A front door placed alongside a front porch may hint at the behaviors of one family, yet a neighborhood populated by this combination of front door + front porch does much more to educate us on the habits, values and identity of a larger and more diverse group of people. In order to properly evaluate the ramifications of an entry door’s situation in space, we must assess its relationship to other entry doors in the same neighborhood. This “collective existence,” as I have termed it, is our next criterion of exploration.

Collective Existence

The relationship between adjacent front doors may never be more illuminated than on Halloween night, when young princes and princesses scurry from one house to the next, challenging each other to collect impressive amounts of candy in very short periods of time. In his article “Why the ‘Trick or Treat’ Test Still Matters,” Brent Toderian, a prominent urban design theorist from Vancouver, cites children as the best evaluators of a neighborhood’s collective existence, a trait which stems from their innate ability to read neighborhoods and to find comfort in areas where the front door is easily located. These areas are also usually high on the “Halloween Door Density” scale, where transitions from one door to the next are quick and effortless[1].

While physical proximity is the most evident enabler of a seamless progression from one entryway to the next, there are numerous other design criteria that create communities in which children and their supervisors are inclined to experience feelings of comfort. A well-lit front door, for one, will augment comfort by alleviating darkness and increasing feelings of safety, acting as a beacon for anybody trying to find their way. A house with less trees and foliage in the front yard also allows for more surveillance, minimizing the chances of surprising or unwelcome encounters en route to the entry. Even more, front doors flanked by sidelights or windows enable homeowners to view the street from within, both watching out for their own safety and the safety of passersby on the street outside[2].

All of these elements – lighting, landscaping and architecture– point to the importance of interior design and its collision with other design disciplines, and to the effect of this collision on the surveillance of a neighborhood, which together begin to define a neighborhood’s “quality of design.”[3] The level of surveillance, I would argue, is perhaps the most important criterion for evaluating a town’s safety, and points to the camaraderie (or lack thereof) of the people living in it. One urban theorist notes that “community completeness” is generated when “the power of nearness” is born, through intentional design moves that include “good visual surveillance through doors, windows… porches and ‘eyes on the street’” that create “legible streets that let you ‘read’ the neighborhood easily. All of these are great for walkable, healthy, economically resilient communities year-round.”[4]

While Frank Lloyd Wright’s prairie houses offer cerebral and poetic experiences for their users, a community comprised of these houses provides little surveillance, challenging a community’s ability to facilitate the completeness and nearness that Toderian praises. Nevertheless, the various styles of suburban house design confirms the importance of the design of the front door – its location, accessibility and relationship to its surroundings – in defining the experience of its users and of an entire community.

Usage

The first two criteria – a front door’s situation in space, and a front door’s collective existence – help us understand the household in the context of its relationship to other households in the surrounding vicinity. Our third area of discussion, the use of the front door, aids in our understanding of domestic life inside of the home. While the front door’s situation in space certainly plays a role in defining its use, today’s suburban houses often have multiple methods of entry. The way these entries are used (or not used) can help us understand the dynamics of the domestic interior.

For example, those of who reside in houses with attached garages often park our vehicles within that garage, causing us (out of efficiency) to enter or leave the house through the door that bridges the interior of the home and the interior of the garage. Those of us with rear house parking may prefer to carry in our groceries through the mudroom door, which is often located at the back of the house and situated in closer proximity to the kitchen or pantry inside of the home. Both of these options leave the front entry door as a vestige of what it once was, relegating it to a formal entry for non-familial guests, less familiar neighbors or mailmen.

Still, many of us may prefer our formal front door as our entry of choice, or the front door may be the only option for entering. When this is the case, it is interesting to ask how this singular method of entry changes in response to the arrival of different visitors; for instance, it may be left unlocked or entirely ajar when one’s children are running in and out with their friends, or it may be paired with a screen door when guests are arriving on a sunny and warm Easter Sunday. For those in areas with increased security, the door may never be left open, but instead may be paired with a peephole or camera that allows the user to observe their visitor before granting them entry.

These habitual entries are evidence of how residential design has shifted and evolved throughout the years, and are indicators of how they may change in function in the future. In prior centuries, back doors were reserved as the method of entry for house staff (maids and butlers being relegated to interior circulation at the rear of the house, near the servant quarters), while the owner and their guests entered through the formalized front door. Today, rear doors are commonly used as the entryways for family and close friends, while the front door is relegated to the less familiar salesperson or trick-or-treater. By observing the patterns of use of the front door, for both those within and outside of the household, we can gain a better understanding of domestic life and the habits of a community.

Materiality

Our final section of exploration, the materiality and visual appearance of a front door, points to various aspects of a household’s individual or collective identity. Its color, for instance, has been hypothesized as an indicator of the owner’s personality and preferences; House Beautiful suggests it is a “portal to your personality – not just your house,” identifying those with yellow front doors as the most individualistic, those with orange front doors as the most modern, and those with black front doors as the likely socialites, with crowded schedules and classic taste.[5]

In contrast to this individualistic assessment, the style and materiality may instead reflect the aesthetic inherent to the country of residence, thereby contributing to a collective voice and hinting at domestic practice inside of the home. These design choices may be byproducts of the economics of the city (is the timber locally sourced, made from reclaimed barn wood, or imported from the rainforests?), or may reflect the economical philosophies of a culture. Furthermore, the door and its décor may indicate the wealth of a household (a custom forged iron pull, for instance, is more expensive than a standard bronze knob), or it may reveal a religious faith, if framed by colored lights or accompanied by a holiday wreath.

In addition to the materiality of the door, its construction reveals additional aspects of an individual’s and a community’s identity. A solid plank door, for example, may suggest an extreme hot or cold climate, and may also hint at a resident’s preference for privacy. In opposition, the owner of a glass front door may place value on added visibility and surveillance, may want to introduce the element of natural light into his home, or may want to capture its reflective materialistic qualities (Figure 4).

Frank Lloyd Wright sought to harness natural light as a material, using it in combination with leaded glass, which together dissolved the rigidity of a solid wall and shifted it towards that of a screen. This “light screen” opened up space and blurred the division between interior and exterior, thereby simultaneously reinforcing the overall architectural character of the house and enhancing the lives of its users by bringing the exterior inside.[6]

Conclusions

By cumulatively analyzing a front door’s situation in space, its collective existence, its use and its materiality, we can begin to obtain a more holistic understanding of the identity of a neighborhood. Not only will we start to comprehend the personality and character of individual households, but we will also come to understand a community’s social habits, its culture, its level of safety and how it balances the public and private lives of its inhabitants.

As we move into an age of increased technology, sustainable thinking and heightened security, we must question how residential design will change, how the front door will continue to evolve and how we, as creative thinkers, can harness the inherent influential properties of the front door. Certain designers are already beginning to question its function, presenting exciting proposals that challenge traditional design thinking.

In Mumbai, for example, the exterior façade and interior walls of a house are comprised of the same surface – repurposed front doors – collaged together to form the shell of a house built for a family of four generations (Figure 5).

Not only does the Collage House encourage sustainable practice by employing front doors as a material unto themselves, but it also brings to light the symbolic importance of the front door, as a personification of family, of security, and of welcoming others into your home. Even more, the doors serve multiple purposes, behaving as both door and window, augmenting surveillance, and bringing in a healthy abundance of natural light.

On the product design scale, Japanese designer Nendo proposed seven different doors that call into question how we use it, and how its materiality relates to its specific function. Lamp fuses the light source with the door (reminding us of how young trick-or-treaters travel from house to house finding their way), Baby creates user-defined doors all within a singular frame (acknowledging the varying body heights of its different users), and Corner reimagines how a door can be situated, suggesting that it can bridge two edges and consequently reconfigure interior and exterior layouts (Figure 6).

These proposals are just two inspiring interpretations of how we can begin to rethink the front door, and are powerful examples of how the front door influences the everyday lives of its users. Furthermore, they are examples of how one element of interior design interacts with and informs other design and socioeconomic disciplines, and how together they have profound influences on the habits and behaviors of its users and of a community as a whole.