Members Only - The private life of the gay and bi-sexual, male sauna

ShareThis paper explores the typology of the gay sauna, examining the design process behind one of London’s largest and most frequently visited venues, which the author designed. It ponders the dichotomy of society’s acceptance of the expression of sexuality, against the concealed, clandestine nature of such establishments. It exposes, partially, the arrangement and materiality of a hidden interior and juxtaposes the safety that this space engenders with that of ‘home’.

‘Space is a pressing matter and it matters which bodies, where and how, press up against it. Most important of all is who these bodies are with: in what historical and actual spatial configuration they find and define themselves.’ Elspeth Probyn. [1]

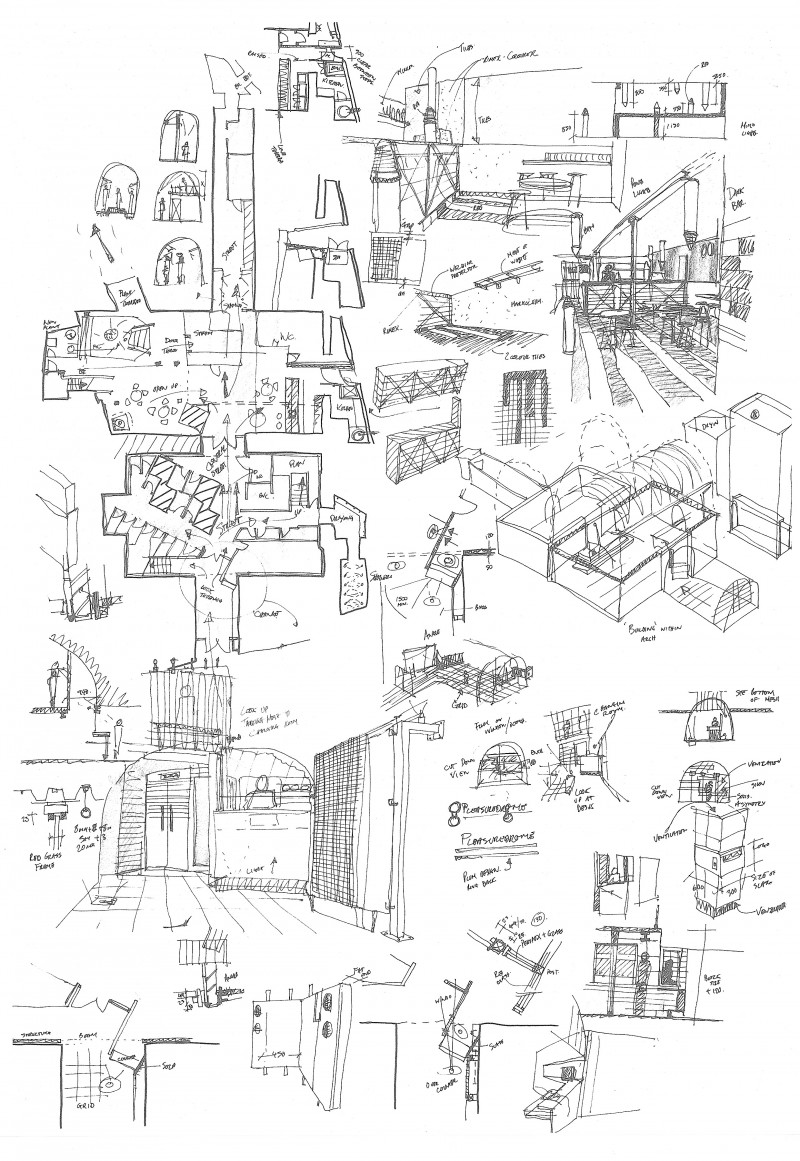

In 2004 I was commissioned to design Pleasuredrome which would go on to become, arguably, London’s most visited, gay and bi-sexual male sauna [Figure 1]. It is the only venue of this type to be continuously open 24 hours of the day, seven days a week, every day of the year. It is also the only interior of this type to receive recognition from the D&AD awards (annual awards for the design industry). A clandestine space, inaccessible to the general public, the entry criteria is based upon age, gender and sexual orientation. Customers use the space as restaurant, bar, psuedo-hotel, cinema, club, washhouse, spa and Grindr meet-up joint, staying for up to 12 hours at a time. It is a sexual space where encounters are nurtured and stimulated. A hidden world, always populated, within an island site under a railway, part of the city, yet removed.

We all understand the need for a safe space, a place where we ‘can be ourselves’, for many of us this safe space manifests in the idea of ‘home’. While I will not attempt to explore the myriad interpretations and theories of ‘home’ here, it nevertheless connotes belonging and familiarity and establishes feelings of security, acceptance and comfort - all principals which make one feel safe.

Home also provides a rare opportunity for concealment from the outside world. Members of the gay community however may have had to experience a fracture from their traditional family home, with all of the embedded sense of security this provides, particularly when family members have been unable to fully accept their sexuality. Duyvendak and Verplanke outline a situation many gay men and lesbians experience, ‘since their family homes were often quite hellish for them – with family members rejecting their sexual preferences… they often had to look for new places that could become their home’.[2]

Pleasuredrome is very well attended on Christmas day when some of the customers are unwilling and/or unable to return to a judgemental family environment. This displacement from home, a space which many of us take for granted, is not of course unique to the gay community. As people leave the places of their past, by choice or through necessity, it is common to sometimes want to regain the sense of safety that has been lost. While a new circumstance can be exciting and offer great potential, the transitional process can also be alienating. A new environment whether country, city, building or interior, can give rise to anxiety as well as opportunity. The need for a place where one can be, express and realise oneself, explore shared histories, increasingly has to be sought, at least temporarily, within the public realm.

In his writings on Third Place Ray Oldenburg describes the ‘neutral ground’ in which ‘no one is required to play host, and in which we all feel at home and comfortable’. [3] The rise of interest in such spaces gives testament to an interior’s ability to ‘arrest transient and timid inclinations, amplify and solidify them…thereby grant us more permanent access to a range of emotional textures’.[4] While this describes the inner, restorative quality of certain buildings, specifically their interior spaces, more typically third places offer the foundation for an environment where we can connect, be understood and be valued. The need for spaces which provide refuge, the ability to be concealed from outside observation, while also offering connection to people who may provide some level of affinity, is an understandable human aspiration. If this private life cannot be found at home then we must look elsewhere.

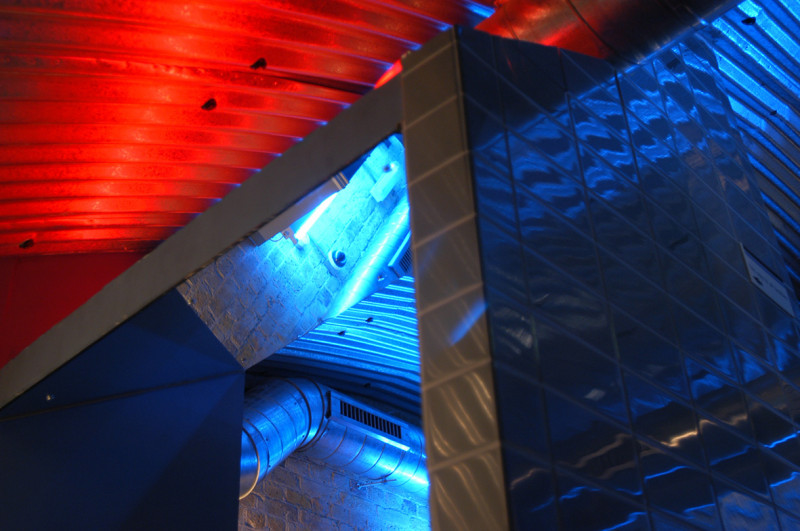

The staircase [Figure 4], which continues the route, begins to envelope the customer further shielding and protecting them from view. In some areas we exposed the existing brick wall [Figure 5] so that the layers of protection, which make up the enclosures, are revealed. Lockers, used as walls, divide the large volume of the changing room into smaller compartments. An angled mirror [Figure 6] mounted above the second stair, allows views from the changing room down into the ground floor. This entrance sequence happens before the customer descends into the main spaces of the venue. All has been designed so that the space gradually pulls the viewer into the hidden interior, slowly removing the outer environment.

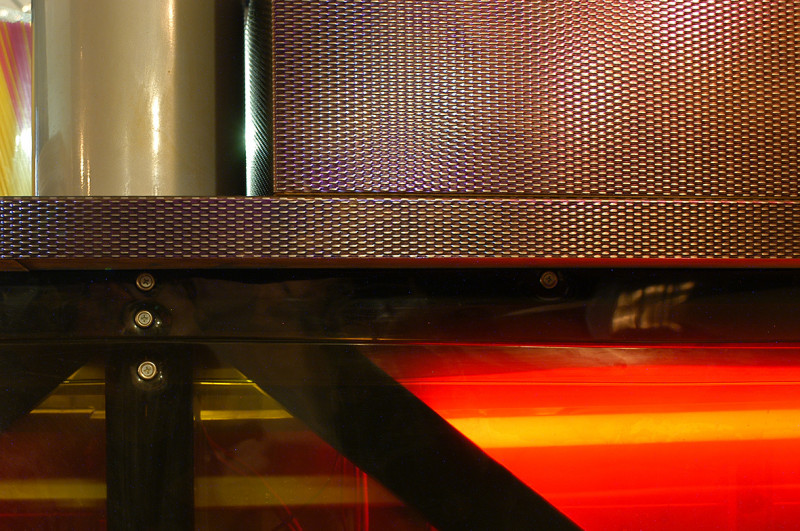

The themes of exposure and protection continue into the inner areas of the venue. The bar’s vinyl front looks incapable of supporting the heavy Rimex counter above [Figure 7]. Barrisol panels overhead [Figure 8] reflect slightly distorted views of the spa pool. Concrete and brick provide the textural counterpoint to the recycled plastic and acrylic screens. Materials sit on top of other materials, detailed in a way to show the intention of support, screening and layering.

As it never closes, Pleasuredrome is often a party space, sometimes a refuge, at times both. The design attempts to reflect this paradox. The spatial variance of the main areas tries to allow for alternation between prowling and solace. We agreed with the client that the space should be most akin to the feel of a nightclub, a place where traditionally intentional and coincidental encounters are contained and enabled. The interconnectedness of the arrangement of the spaces provides opportunities for voyeurism and encounter, while the larger areas [Figure 8] soon break down into smaller, quieter locations [Figure 9].

No windows exist to the street within this environment, accentuating the feeling of removal from the outer world’s complexities. It is tempting to provide floor plans of the premises within this article, however I feel this would render the fabric of the building transparent to the viewer and therefore not in keeping with the spirit of concealment, which the design tries to implement. While the act of ‘coming out’ implies a spatial imagery, moving from the privacy of the ‘closet’ to the openness of public acceptance, the sauna space contradicts this notion, remaining concealed. It is only right, in my view, that the hidden is revealed “through a glass darkly”, so that the user’s privacy is not open to scrutiny. Like so many private member’s clubs, part of the appeal is their inaccessibility. A gay sauna provokes intrigue due to the need for discretion to remain paramount. Through the design I attempted to provide a safe space which fulfils the expectations of a very specific user group, albeit a space where those users normally wear only a towel.