Affective reasoning: hidden interiors

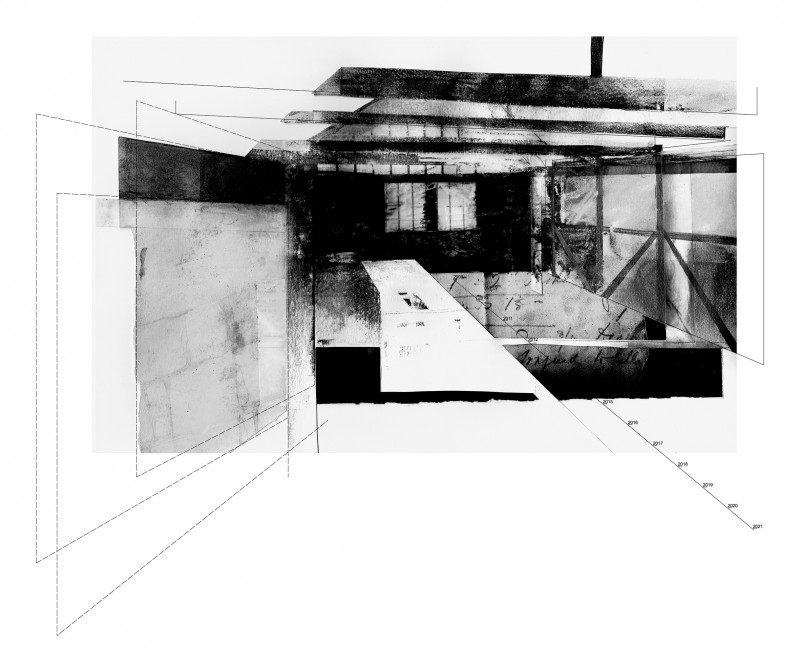

ShareThis essay explores the role of affective reasoning in a design process; examining what could be referred to as an initial instinctive response to a space and questioning its value and merit as a strategy for analysis and cognition. Employing a range of methodologies, drawings, making, photographs and printmaking, we carefully examine, investigate and analyse a forgotten and overlooked space.

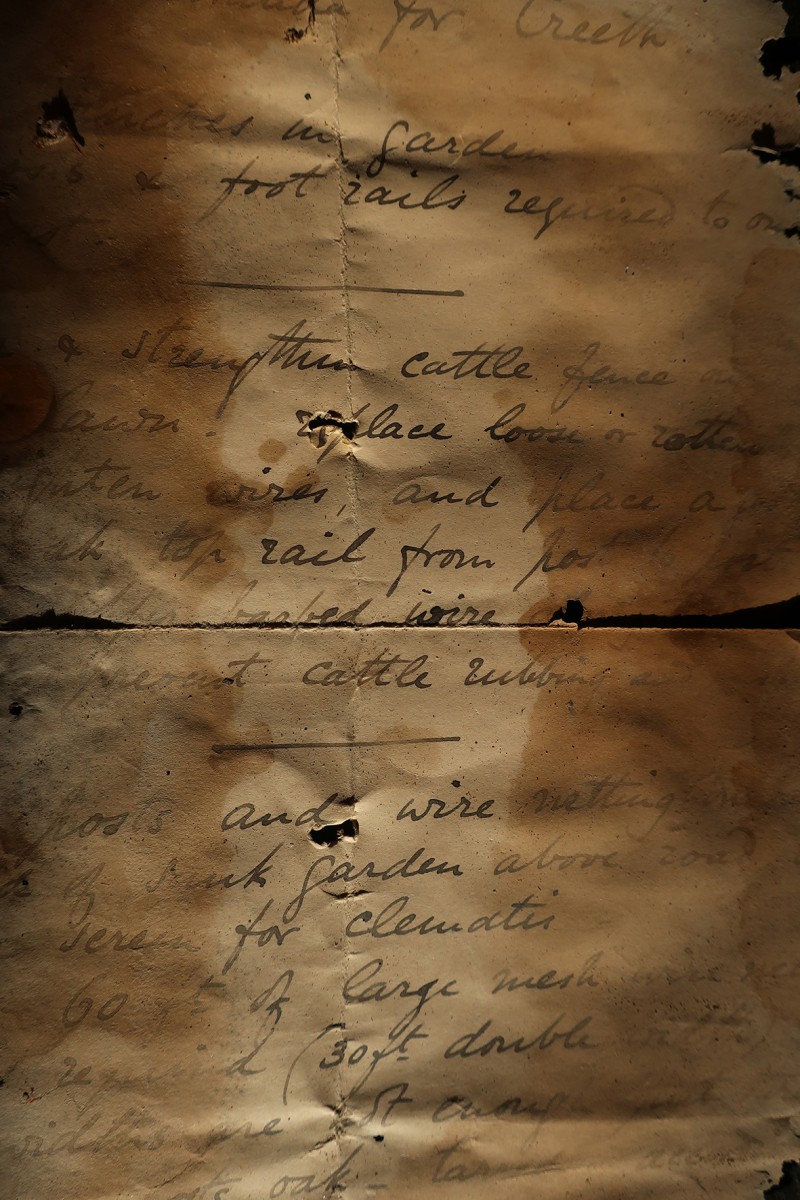

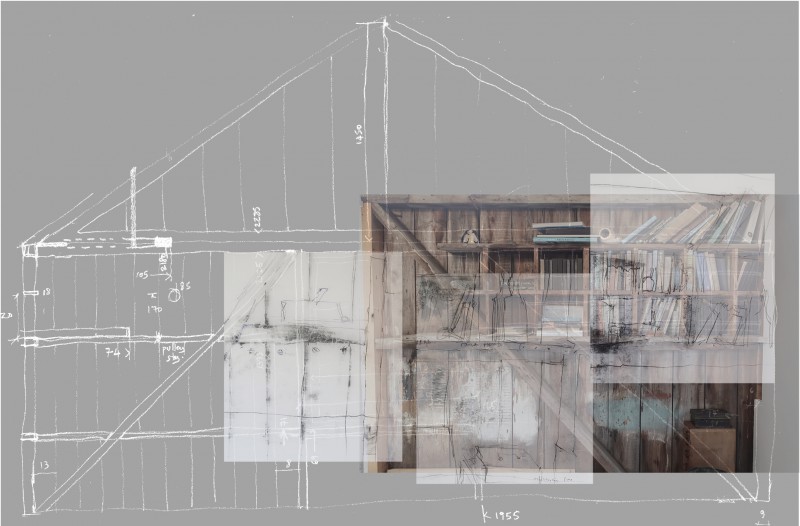

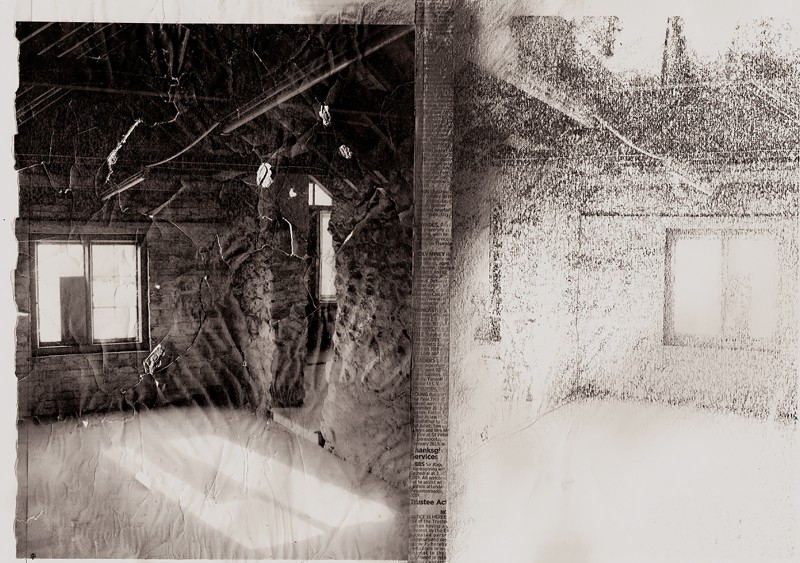

A 300-year-old dilapidated builder’s workshop packed to the rafters with paint, metal, tools and construction materials, obscuring the character of the host building and it’s inherent qualities. The occupancy was utilitarian and functional. Blocking windows, goods stacked on the floors and tools leaning against the walls concealed the echoes of previous lives, forgotten and undervalued. Beneath this detritus the old flag stones, stained with grease and paint emerged. The brick and timber walls were framed with ad hoc shelving and daylight worked deep into the plan.

This space resonates, we sense and see the possibilities of the existing building. Can the designer intuit the latent atmosphere of a space, employing affective reasoning[1] through drawing and making to examine and clarify the essence of the found object?

This document is a record of the conversion of this builder’s workshop into residential use. A 10-year longitudinal study of the evolution of the interiors: an archive of drawings, photographs, thoughts and notations.

As ‘temporary custodians’ our aim is not to mimic but to respect and be sensitive to the building’s inherent materiality; to register a light footprint on its surface whilst maintaining the integrity of the found object, ever mindful and questioning at what point is the character of the space erased? Our ambition was to make apparent the intangible qualities and elements sensed but not necessarily seen.

“I think we are always searching for something hidden or merely potential or hypothetical, following its traces whenever they appear on the surface.”[2]

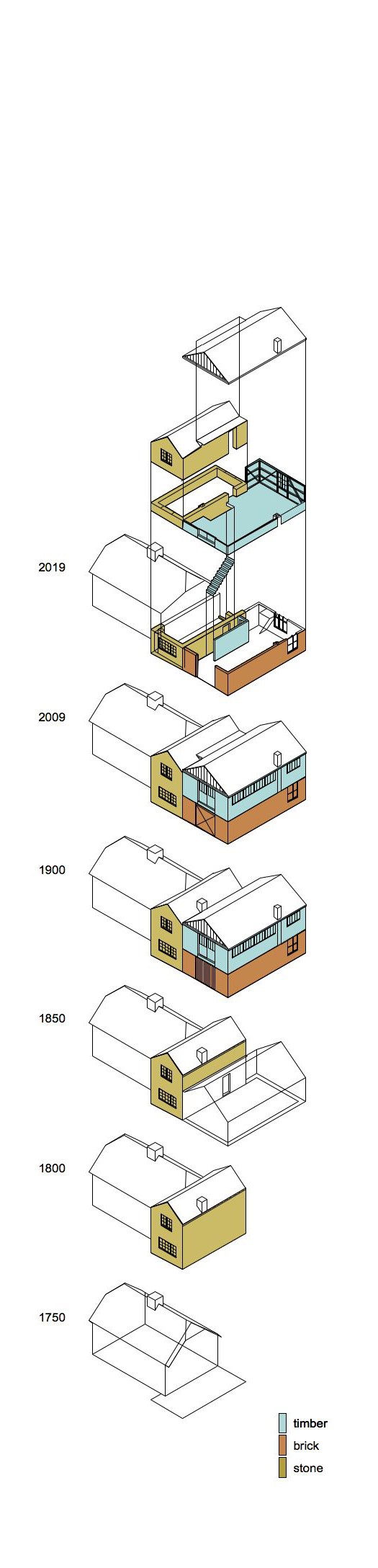

The Workshop sits in the centre of a village, opposite a 12th century church at the Southerly tip of the Isle of Wight. Historic newspaper reports tell of smugglers concealing rum in its garden, but latterly it was used as a general builders and glaziers workshop. The building has been constructed incrementally over the last 300 years from local limestone, handmade bricks and softwood timber. A stone workers cottage, a brick store with a timber shed at first floor; it is a narrative of pragmatic occupation and form follows need.

However, there was something within this building that resonated within us, demanding value and respect. We did not commence with a rigid concept, but continually touched and felt our way through haptic encounters, taking the phenomenologists stance as a guide. “In every dwelling, even the richest, the first task... is to find the original shell... to determine the profound reality of all the subtle shadings of our attachment to a chosen spot.”[4]

Working empirically with materials, learning traditional techniques such as lime mortaring and adding flint teeth[5] to buttress the structure has enabled us to connect with the lives and craft of the previous occupants, unveiling and deciphering narratives old and new. Over time, by listening to the building and researching its inherent properties we have enabled the building to breathe again.

This is an account of this process of investigation, interpretation and design intervention: documenting our practice, outlining specific tools and strategies. “In order to create extraordinary spaces with integrity and atmospheric presence we need to identify what we find valuable, what we are moved and inspired by.”[6]

01 -being attentive to

02 -slow looking

03 -mapping habits and preoccupations

Analysis of our photographs and drawings showed a preoccupation with the diurnal passage of light. Due to the abundance of daylight at first floor in the timber shed it was an easy decision to determine this as the primary space, a flexible studio and living area. Establishing this as a datum, anchored sequential design decisions. In contrast, the ground floor of the brick building was inherently dark, the floor cold and damp. To bring in the morning light we introduced an east window, the southern wall opened up to the garden and to the west, an existing window restored. [Figure 4]

A small wall-mounted water heater, old workbench and camping stove served as a temporary kitchen for several years as we observed our natural predilections and rituals. In turn, the kitchen has established itself in the core of the ground floor, mediating between fireplace, entrance and staircase. Previously used as a garage and store, it’s heavy flag floor bears traces of oil and spilled paint. The flags were diligently ordered and numbered before they were lifted for the fitting of insulation and underfloor heating. When replaced, the stones have been left unsealed in order to continue to register the passage of time and use.

04 -reconnaissance

Other surveys have been longer to mature, movement ties installed on cracks gave seasonal readings, signalling other criteria; in winter the water table rises and the stone cottage begins to swell. We do not aim to seek perfection and fine finish within this space but accept it’s organic fluctuations. Designing with a tolerance for imperfections, materials are chosen for their ability to mature and season well. Waxed oak, natural leather, lime finishes and breathable paints that can creak, crack, discolour and stain over time.

05 -scrutiny

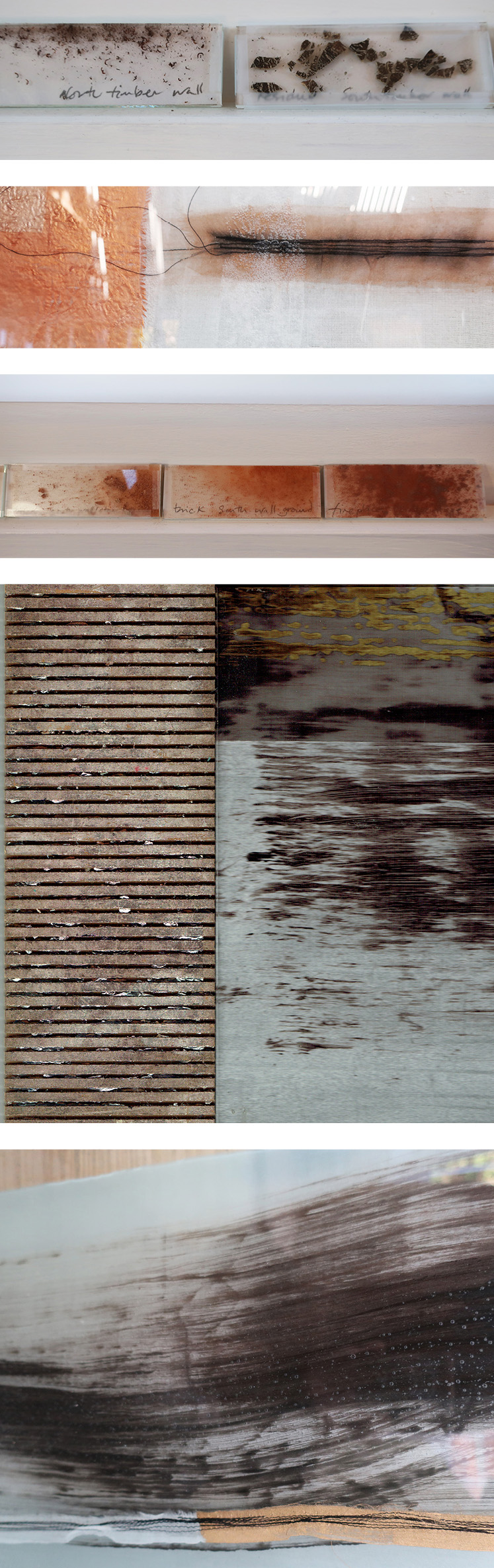

To examine the colours and textures resident in the buildings fabric, we employed the tools of the scientist: using scalpels and laboratory slides we worked sequentially around the walls, documenting location and materiality and collated tiny fragments of residues for examination. Encapsulated in layers of fine glass, hidden subtleties were unveiled and laid open to interpretation. From the stonewalls we gathered fine dust, from the old rafters lime wash was registered, other timbers showed oxidised wood fibres blackened with age. From the spine wall dark grey bitumen was recovered and brick samples from different locations, evidenced gradation of pigmentation that we had not been aware of.

06 -distillation and assimilation

The potency of the initial investigations lingered with us for several years prompting further research. A requirement for privacy in the bathroom and screening from the street brought us back to the qualities identified in the small-scale microscope slides. Through a process of distillation and assimilation: testing various materials, mark making, stitching into tracing paper and silk, scale models and full size trials, we explored numerous iterations. [Figure 6-7]

It was important to provide enclosure yet allow the found volumes of the building to remain, barely touched. These insertions have become a series of architectural "membranes": that enable light to suffuse through the section of the building. Made from silk laminated in glass, the intention is that these panels are notionally transitory: constructed in a manner that implies impermanence. They currently illustrate our personal memories of a landscape and are therefore specific to our period of inhabitance. When we leave, new occupants could easily replace these moments as someone might remove picture frames. At night, two of these screens inserted within the north façade become radiant. The building begins to act like a magic lantern, relaying glimpses of activity, internal narratives and occupancy to the village street.

07 -dialogue

Within recent history, former tenants had established a new "doorway" to the first floor of the stone cottage by simply knocking through the spine wall, the jagged edge patched up with cement mortar. We have chosen to retain the brutal traces of this action, not tidying it up, not repairing it but acknowledging it as another chapter in this building’s narrative. [Figure 8]

By highlighting this scar with copper leaf, we have followed the example of the artist Susan Collis whose work with architectural palimpsests, replaces items like rawl plugs or paint splats with sapphires, diamonds or gold. These precious inclusions ask us to question our notions of beauty and perception of value by drawing our attention to ordinary, everyday marks interred through function and use. This intervention physically highlights the threshold, reflecting the afternoon light and replacing the traditional architrave. The copper leaf is not sealed so over time its vivid lustre will oxidize and fade, its presence will continue to participate in the dialogue between the found object as an intermediary between the old and new.

Harmony and stillness are two significant words that Jim Ede chose to describe his home in Kettles Yard, Cambridge, the latter meaning “to be attentive, to take in, to search” and also just to be there and know.

This sense of stillness, by being there, has enabled us to develop an inventory of cognitive practice. Whilst the initial ‘frisson of the physical encounter’[12] establishes the impetus of a design idea, it is these affective methodologies that have provoked a depth of enquiry, guiding and informing the realization of this concept into built form. Through a process of caring for, repairing, cleaning, observing, listening and recording this building, our sense of “room” has deepened. As this relationship evolved our sensitivity to the qualities that had lain forgotten and dormant over many years has been heightened. In the manner of Genius Loci; the spirit of the place as discussed by Norberg-Schulz, the building has revealed itself to us over time. Our initial intentions have remained constant, but every step of inquisition revealed further evidence and clues, testing our decision making and enticing us to challenge conventions of “wall” and “enclosure”. The reciprocal nature of this experience has facilitated a new generation of narratives that sit quietly alongside their ancestors. Where possible, we have retained the traces that enrich the existent surfaces, the white paint that indicates the impatient act of cleaning a paintbrush, the handmade nails and the smoky residue and kettle hook on the fireplace remain. Old storage shelves previously stacked with pots of wood lacquer, and dirty cloths have become appropriated as bookshelves, [Figure 9] old winches in the roof facilitate the drying of our drawings and prints.

We have also laid new hidden imprints for future sleuths to decipher. In the north elevation, the original window set into the sliding gable doors finished at a height that restricted the view. We had this door carefully removed and the windowsill reduced, so that when seated, the hills in the distance can be seen unhindered: the evidence of this design decision is almost invisible.

In Thinking Architecture, Peter Zumthor recounts a conversation with a friend about the latest film of the director Aki Kaurismaki; by retelling the narrative of the film Zumthor realized what he was trying to say through his architecture.

‘he does not exploit them [the actors] to express a concept, but rather shows them in a light that lets us sense their dignity, and their secrets.’[13]

Postscript:

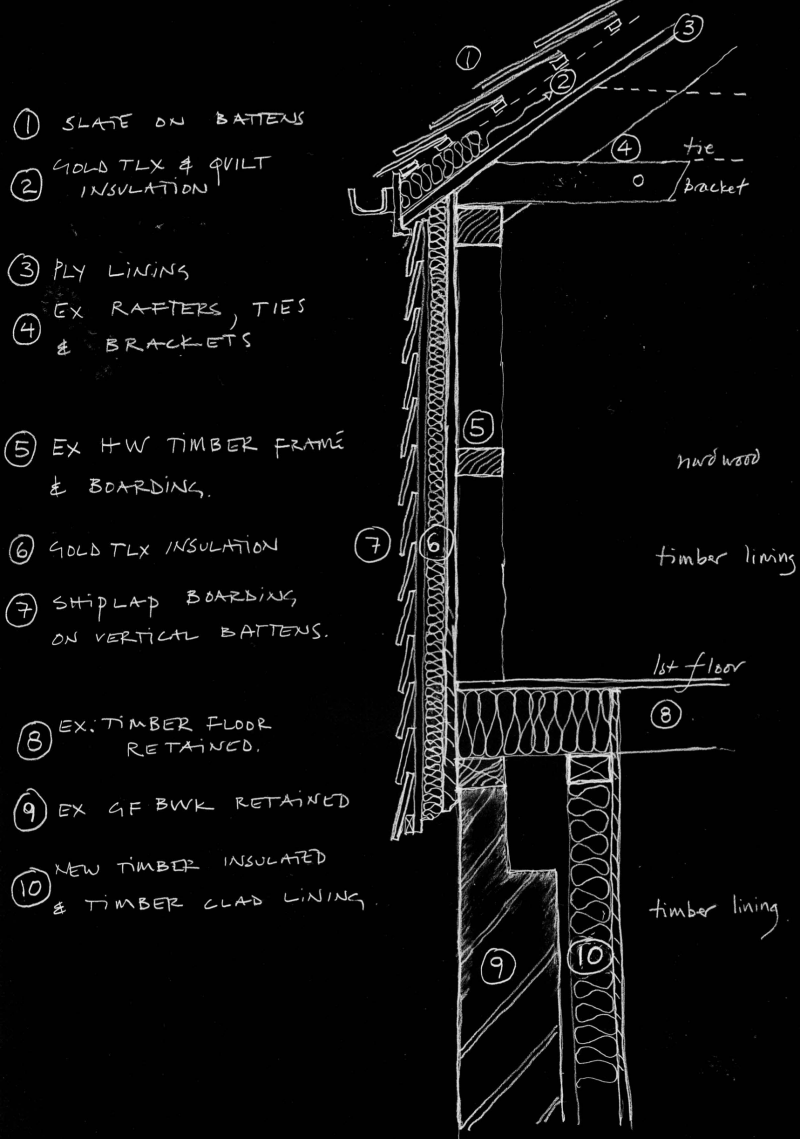

Early design decisions not discussed here, were simply to secure and maintain the body and integrity of the building before it crumbled. All of the lintels were made from hand-sawn timber; the large 9’ x 11’ timber beam holding up the south elevation of the stone cottage needed immediate attention. The west elevation of the timber shed was beyond repair and a whole wall at first floor level collapsed. To maintain the inherent proportions first observed, all the rotten windows were replaced with hardwood units replicated by a joiner in the next village. Only one original window remains, twisted and distorted, sitting as a testament to the heave and movement in the ground.